Who Is My Neighbor?

Long thoughts on characterization and fact in regional housing arguments

This is going to be a long and semi-personal one, so bear with me. But yes, it’s about housing (surprise).

There’s a thing I’ve said before—not here, but to people, in conversation: that going to college made me more conservative. I knew all kinds of people who were into all kinds of lefty causes. Think of anything and someone on a campus is for or against it. Many of these students seemed a little odd, unhappy, angry to me. I remember the feeling that well-adjusted, politically moderate people seemed like a minority. In other words, now that I think about it, being on campus felt like a real-life version of being on Twitter.

My reaction to that was to hold onto my own identity: Catholic, right-leaning, normal. I had my political causes that I was involved in: “real” and sustainable food advocacy, and anti-consumerism. But my understanding of them was as philosophically, if not politically, conservative causes: making do, practicing gratitude, cultivating contentment. It was an accident of American politics that these things were coded as “belonging to” the left. I still think that. And I think the same thing about urbanism.

But going to grad school—public policy school, for an MPP degree, specifically—made me less conservative, or at least, less politically conservative. People there skewed left, but they were overwhelmingly smart, motivated people who wanted to be there. Most of them understood the complexity of public policy issues and had given up the naivete and idealism of the undergrad activists. But they also had a certain idealism, and absolutely meant well.

I realized that so much of what conservatives treated with skepticism and suspicion was really just public policy. That here we were debating things very frankly that some people thought were crazy. We might, for example, discuss mass shootings as a public health issue. Many of the people I grew up around would find that to be a loony characterization, especially after the pandemic made public health a byword, for many of them, for petty tyranny. I realized, also, that a lot of policies are probably designed to look like they’re doing something. Conspiracy, incompetence, etc.

On the other hand, I saw the blind spots some students had, which is to say that young, left-leaning, highly educated people have. One of them posted on social media once about how she considered reporting a rideshare driver because he was playing Christian music on his car radio. She certainly did not understand herself to be prosecuting a vendetta against a Christian working person over his choice of music. She just had an entirely different set of assumptions and expectations. She perceived his choice of music, somehow, as a slight or an attack. I suspect that’s the same way a lot of conservatives view urbanists and our preferences.

If you consume right-wing media, you’ll see a lot of suspicion. A lot of lurid storytelling, assuming the worst of government or public agencies or activists or rising political causes. Not wondering what real problem they may be trying to solve, but starting with the understanding that they hate America and then trying to figure out how this or that policy furthers that assumed goal. There isn’t just a disagreement with policy or ideology. There’s a lurid, fevered element here. When a leftist gets on board with a sensible policy, they don’t see the leftist as more sensible; they see the policy as more leftist.

A good example is Ilhan Omar supporting the repeal of minimum-parking ordinances, or laws which require developers to build a certain number of parking spots. One commenter suggests that the representative wants to turn America into Mogadishu. This characterization has absolutely nothing to do with the policy. But it is very easy to put your understanding of a person ahead of what they do or say or support. She wants to do X, so everything she supports must secretly be about X! Why else would she support it?)

Years ago, I remember a column in Investors Business Daily, a right-wing stock-market-focused paper, about “smart fridges.” The column claimed that the EPA might control them remotely; do you want environmentalist bureaucrats setting the temperature of your beer?

I mentioned the smart fridges the article was dunking on to my manager as a possible item of interest—I was a communications intern with the now-defunct environmentalist Worldwatch Institute at the time—and he dismissed it. “That’s just techno-consumerism,” he said. (“Oh,” my dad said when I recounted the exchange. “I guess he thinks we shouldn’t have any fridges.”)

You saw it with Ebola, and later with COVID. The notion that the Democrats wanted Ebola to rip because it would give comfortable Americans a taste of deprivation. Or Rush Limbaugh’s claim that maybe Obama viewed Ebola as payback for slavery. With COVID, it was the Democrats’ propensity not to let the virus rip that was the dastardly plot; this time, it was overhyping a public health threat to shutter churches, or to lock up good, law abiding Americans while unleashing rioters on cities.

And you see this with housing.

First I want to note that not all conservatives who look askance at urbanism or pro-housing advocacy are far-right people, nor, by any means, do they all have bad motives. Most do not. There’s a lot of mainstream conservatism that in my view simply inherited a skepticism of these issues that is not necessarily strongly held or deeply considered.

I’ve likened it to the tendency of Republican voters to “support” a neoconservative foreign policy. If you don’t care deeply about an issue—and most people don’t care deeply about foreign policy—you tend to outsource it. Average Republican voters outsourced their foreign policy views to whatever was ascendant or mainstream in their party; now many of the same people who were neocons in the Bush years might skew non-interventionist or isolationist. I think a lot of people have done, and do, basically the same thing with the cluster of issues surrounding land use and transportation.

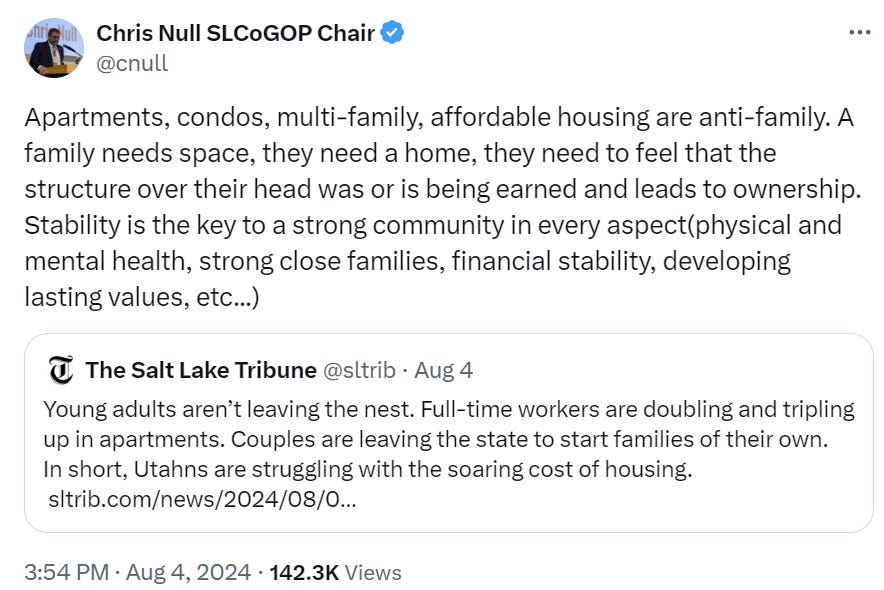

For example, Jonathan V. Last, a conservative-ish writer who’s now very anti-Trump, seems to hold that “inherited” view of looking skeptically at urbanism (though he is also in favor of more housing generally). Here’s a good articulation of it from a GOP party official in Utah. Note that he isn’t really saying this in an angry or heated way. He’s just explaining it as if it’s obvious. That’s how it feels to a lot of folks on the political right. And, frankly, to a lot of older homeowners on the left.

As you well know, I find this viewpoint strange. In fact, I believe that it cannot possibly be true, because that would imply that once we run out of land for single-family houses, we’ve reached “overpopulation”—not an issue that conservatives worry about (and not an issue I worry about, because it’s a phony, made-up issue from the uber-environmentalist left, and one of the major motivators of NIMBYism and anti-growth policies in the 1970s). Families who cannot afford a house need to live somewhere. Beyond that, people who are adult and single also have to live somewhere. In no world do multifamily structures not serve a need for both families and individuals.

All of this is sort of introductory to some articles I’m going to critique below. My point is that when you aren’t familiar with an issue and the way it’s discussed, it’s very easy to view it with suspicion. That reaction feels right, because the suspicious (likely just unfamiliar) thing you’re hearing matches other things you’ve heard.

It’s sort of like, I heard about bike lanes on Fox News, and now they’re trying to put one in my little town! There is no misstatement of fact there; there might not even be a misstatement of fact in a hypothetical Fox bit on bike lanes. Eye rolls and snark, which you might expect, are not misstatements of fact. But they’re characterizations. As is the idea that bike lanes are not specific, useful or not useful, appropriate or inappropriate, pieces of infrastructure in particular places, but rather ideas. Signifiers in the culture war.

It isn’t that the conservative media have uncovered a lefty plot—a characterization that urbanists sometimes ironically adopt to poke fun of people who say that about them—but that the conservative media takes a very normal, real-world question and slots it into this culture war, which then becomes the only frame by which a large share of the country will have ever heard of it.

With all that in mind: I’ve had a series of articles on this topic recommended to me, from a conservative blog called Powerline. For over a decade now, they’ve been on the “war on the suburbs” beat, sort of like Joel Kotkin (you can have fun with the Google search too):

Particularly, they wrote quite a bit about Barack Obama’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing program, which was initially embrace by the Trump administration (!) before Trump’s political instincts overruled his developer’s instinct.

The people at Powerline are lawyers, and they’re smart. But either they know absolutely nothing about housing policy, or they’re counting on their readers knowing nothing. At least one of those can be remedied.

This arc of commentary began, as far as I can tell, in 2013, with this piece: “Obama moves to impose his vision of how we should live, Part One.” Right off the bat, the idea that we have a housing problem and need to fix it—a normal example of doing public policy—is basically characterized as Obama’s personal (and, impliedly, racially tinged) viewpoint, not as something economists, builders, homebuyers, and a large swath of regular people understand to be true. Second, fixing the problem is cast as telling us “how we should live,” while the zoning policies that very much led us to this point are understood as a sort of state of nature.

Or as I put it, when someone says of a townhouse development or an apartment building, “Did the people who live here actually want this?”, I think this is the right response: “Did the people who live here actually want this?”

This is the core of the Powerline writers’ argument:

The AFFH rule is part of Obama’s attempt to dictate how we shall live. I’ve written about this phenomenon under the label of “regionalism” here (relying on Stanley Kurtz’s book Spreading The Wealth: How Obama Is Robbing The Suburbs To Pay For the Cites) and here and here (relying on the work of Katherine Kersten).

In essence, President Obama seeks to fulfill the left’s longtime dream of redistributing money from the suburbs to the cities and inner-ring suburbs, and imposing racial and income balance in every neighborhood.

Terry Eastland, writing in the Weekly Standard, explains how the new HUD rule would enable the federal government to use its power to create communities of a certain kind, each having what the government deems an appropriate mix of economic, racial, and ethnic diversity.

Look. I guess you can say “I like living in a mostly rich, mostly white neighborhood.” I’m not really going after that here. But I don’t think you can argue that that arises naturally, i.e. in the absence of public policy intended to engineer it. This is a sort of tricky question: zoning had, and in some instances was intended to have, exactly this effect. How exactly you undo that, and how you avoid remedying that problem turning into “suburbia is inherently racist” or whatever the reductio ad absurdum of progressive housing advocacy is, is a hard question.

What I can say is that it can be demonstrated that suburbs are a financial drag on denser urban cores, and that cities have and do effectively subsidize suburbia.

But on the question of dealing with the legacy of zoning, take this bit:

By requiring the use of statistical analysis to infer the existence of “unfair housing,” HUD is imposing on states and localities its view that unfair housing means much more than discriminatory housing, a view that the Obama administration has turned summersaults to insulate from Supreme Court review. For HUD and for those who accept its money, unfair housing encompasses any race-neutral policy that has the “effect” of creating “disparate access” for minorities to good jobs, schools and other suburban “assets.”

I understand what they’re saying here: how can you just declare that in any case where black people don’t have the same outcomes as white people, racism is necessarily to blame? On the other hand, what’s the flip side of this? That as long as nobody says “This policy is going to segregate people by class and race, and we’re going to say that very clearly!” then…there’s no recourse? That localities—which derive their land-use powers from the states, based on the expectation that they will use those powers for the public interest—have unlimited power in this realm? Put it that way, and it doesn’t sound so conservative.

In any case, while we can argue over the old question of disparate impact versus intent, the idea of laws that are “facially neutral” but are intended to have…specific effects is very much an element of legal analysis. Which, of course, any lawyer would know.

These articles continue, with a part 2 later in 2013, and a 2020 piece warning of “The coming war on suburbs” (didn’t that war already happen in 2013?)

The 2013 follow-up recounts the “harrowing” story of Westchester County (median income, north of $114,000):

Westchester County made the mistake of entering into a settlement with HUD, regarding it as a reasonable bureaucracy based on its experience with the Bush administration. Unfortunately, the settlement was with Obama’s HUD.

Under the settlement, the County agreed to build 750 “affordable housing units,” 650 of which would be in municipalities with less than 3 percent American-American population and less than 7 percent Hispanic population. HUD insisted on this deal even though Westchester County had not been accused of engaging in housing discrimination.

Must one prove “housing discrimination,” per se/strictly speaking, in order to recognize that an entire county at that sort of wealth level, at the doorstep of one of the world’s greatest cities, is not naturally occurring? That the diversity which the Obama administration in some sense sought to engineer was really the diversity that would have existed naturally, in a New York metro region that did not have land-use controls effectively preventing it?

Some more:

As further penance for its non-wrongdoing, Westchester County agreed to advertise its affordable housing units to people living outside the County. The non-residents were to be lured into the County to try to ensure that the new housing units would be filled by the desired number of members of the HUD-preferred racial and ethic groups. To this end, Westchester County was required to spend money on behalf of people who don’t live there. This is “regionalism” in action.

It is also a form of “steering.” Racial discrimination in housing has traditionally occurred when realtors steered clients from one neighborhood to another according to where, based on race, the realtor (and forces behind the realtor) thought they should live. Now the government is steering people into certain neighborhoods based, once again, on race.

Westchester County has proceeded apace with the building and steering called for by the Obama administration. But the Obama administration isn’t satisfied. In line with its proposed AFFH rule, it now calls for 5,000 more affordable housing units to be built, most of them in predominantly white communities.

This would require re-zoning, which HUD expects Westchester County to impose.

“Steering” is classically when realtors subtly or non-subtly try to get (usually white) clients to buy in more affluent and more white neighborhoods. So the Powerline folks are essentially accusing the Obama administration of “reverse racism.” Clever. The problem is that what the administration was doing, as far as I understand, was not based on “should”; it was a not a black president’s preferred racial and ethnic mix. It was a widely supported set of policies meant to restore something like a normal socioeconomic mix.

Part of what I’m doing here is trying to tease apart what these guys are doing: how they craft a narrative out of a handful of facts and interpretations and associations. How they get you to fill in things that aren’t quite true based on things they aren’t quite saying. And frankly how easy it is as a reader—if this is the only sort of opinion you’ve encountered on this cluster of issues—to feel convinced. To feel like you’ve figured it out. I think very often about how easily I could have inherited these views. It’s precisely because I didn’t that I feel hopeful about convincing conservatives or at least enticing some of them to think about these things anew.

But I’m also obviously arguing against these points. So a little more of that.

Yes. There aren’t that many poor people in Westchester County. Some, of course. Not a ton. That isn’t because Westchester County has “solved” poverty. It’s because it has pushed it out. That’s the whole point: that an entire county at the doorstep of the greatest city in the world is effectively closed off to everyone who isn’t rich. This is not normal. It’s a highly anomalous result of a distortion of land use and housing policy—the local government telling us “how we should live.”

What is probably normal is exclusive streets, or even exclusive neighborhoods. Mansion row, Beverly Hills. What is not normal is exclusive cities or counties or entire metro areas. I do not think you need to prove that this is a deviation from an organic housing market any more than you need to prove that starvation is disastrous to human health. The phenomenon itself is the signal that something has gone wrong and something has to change.

Folks like the Powerline bloggers, and lots of NIMBY homeowners, will acknowledge the failure of the public housing towers, and they’ll oppose required percentages of affordable units in new buildings, or whichever way we do affordable housing today. What they won’t do is offer some actual solution of their own. That is because, outside of what they oppose, there really isn’t any. If you think anything should be done for the poorest people, then it seems to me the inclusionary zoning idea or something like it is pretty logical and reasonable. Of if that doesn’t work, something else. Public housing not in a high-rise form? Rent control (not my choice; I’m a housing supply-sider)?. Something. At least an acknowledgement that there is a problem.

When we pretend there is no problem—when we’re in a position to imagine there is no problem—people who already aren’t making all that much money are forced to either live in crowded and sometimes illegal arrangements, or they’re forced to undergo a long commute.

The idea that an entire county—not a street, not a neighborhood, not a village or town—would ban the construction of any of the sorts of homes that many of the people who work there could afford to live in is misanthropic and kind of absurd. These communities do not have the people to advocate for affordable housing, because they have pushed those people out, misusing zoning not to regulate development but to shut it down.

And so, in order to reverse this artificial, engineered state of affairs, of course “outside pressure” is needed to stop communities from sending their own workers to other localities to be someone else’s problem.

I’ve seen it stated more explicitly than the Powerline pieces, but conservative media crafted this narrative that everything was fine until Obama decided the suburbs were too nice, and they all needed a little sprinkle of urban disorder. A little, you might say, color. I can’t be too harsh, though, can I—many of these people have no idea there is a real housing crunch. A lot of people have literally never spoken to someone who identifies as an urbanist. Many haven’t shopped for a home in the last 15 or 20 years. Many live in quiet settings where very little development typically occurs.

The only data points a lot of homeowners have are “Obama said something about suburbs not building enough low-income housing” and “suddenly all these ugly apartments with a low-income units set aside are popping up.” It is genuinely difficult to discern the difference between “Why is all of this suddenly happening?” and “Huh, I’m suddenly becoming aware of it.”

Meanwhile, the “scary” idea of setting aside a percentage of new units to be affordable has a long provenance. As a pure matter of fact, it was not invented by the Obama administration to target affluent suburbs. It was a somewhat more market-oriented alternative to the disastrous public housing projects of the 20th century, which warehoused and concentrated poverty, and seemed to exacerbate its ill effects.

The opposite of that is to pick a low percentage of affordable units for every development—not to “make sure everyone gets a little poverty,” but to dilute whatever it was about concentrated poverty enough that it does not perpetuate and reproduce itself. There are no longer “nice developments” and “low-income projects.” This idea arose in the 1970s. Montgomery County, Maryland has been doing it for decades. It has not cratered property values or turned buildings into slums. One of the loveliest housing developments I’ve ever visited, in Rockville, has inclusionary zoning, effectively meaning a small percentage of the units are income-restricted. I challenge anybody to identify the “poor people’s homes” in this development.

The idea that entire counties and entire metro regions becoming unaffordable even to people of average means, let alone the poor, is not a problem of public interest, is simply untenable.

I want to wrap this all up by focusing a little more on one of the arguments here in particular—the issue of these affordable units being advertised to people from outside of the community. I hear this in my hometown of Flemington, New Jersey, about how they’re building low-income housing and advertising it to poor people in Newark, or wherever.

“We’re being forced to pay to house other localities’ poor people” is not a statement of fact; it’s a characterization. So here’s another characterization. Those people are your people. In two senses: one is the point above, that artificially high housing prices that act as a class filter have in fact pushed “their” poor people outside of their boundaries.

But secondly, every community needs various working-class and manual-labor jobs: janitors, maids, security guards, construction workers, landscapers, roofers, nannies, house cleaners, the people who pick up and drop off laundry and deliver packages and groceries. And then the better paying but not glamorous jobs like teacher, fire fighter, entry-level cops, garbage pick-up, and lots of other jobs.

And in many instances, the richer a place is, the more of these services it will demand. In Long Island and the New York City suburbs, where most houses are on small lots, the mix of jobs will be different than out in central Jersey, where many people live on large lots, anywhere from one to five acres.

But affluent neighborhoods will be calling contractors and handymen and hiring nannies and having their laundry picked up and delivered back and in general availing themselves of labor-intensive services more than less affluent neighborhoods.

These communities want to enjoy the benefits of low-cost labor, but they want to export the costs. They are effectively importing jobs and exporting people; demanding that other localities house their workers, because they want to hire them but not live near them.

We treat our working-class people like a liability, always saying “somewhere else.” Well “somewhere else” is not a place; everyone says “somewhere else.” New York City itself, for God’s sake, has NIMBYs who still pretend there’s a “somewhere else.” We hope that we can keep on hiring people and keep on making things run without having to have these people near us. We play musical chairs with them and hope we can leave somebody else holding the bag.

So we can argue over the solutions at the edges—the details, the implementation. I’m open to that. I’m not wedded to Obama’s AFFH program, okay? But I offer you this first: if someone is good enough to deliver your packages or mow your grass or tar your roof or clean your house or be a nanny to your kids, then they’re damn well good enough to be your neighbor.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,000 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Cathartic. Thanks for the rant (I say that in the best way).

It’s worth remembering that the “freaking out about overpopulation” Thing dates back to Malthus, who I don’t think can be reasonably described as “Uber-environmentalist left”.

Beyond that nitpick, I’ll argue that the overpopulation scare caught on because it was Useful to a wide array of jackasses: heavy polluters got to blame third-worlders (and China) for their pollution, 70s Environmentalists (truly one of the most self-defeating groups of all time, thanks to their opposition to nuclear power) got A Big Issue to rally around, racists got to say Something Must Be Done about China and India, The Media got to make scary predictions and thereby get more eyeballs on televisions, etc.

Alright, now that’s off my chest—back to the article!