Readers: This week marks the completion of the third year of The Deleted Scenes—that’s three full years, every day except Sunday, of thoughtful, illustrated, locally rooted pieces on urbanism and more. I’m offering a 20 percent discount for new subscribers, good until the end of Sunday. If you’ve been on the fence about upgrading to a paid subscription, this is a great time. Your support—whether reading, sharing, or subscribing—keeps this thing going. Thank you! To another year!

In a recent issue of his newsletter The Triad at The Bulwark, Jonathan V. Last featured a piece on the “California Forever” project, a bid to build a new but traditional city from scratch. He writes from the perspective of a Catholic with a large family living in the suburbs, and I suspect he speaks for a large number of everyday Americans, particularly, but not only, those who lean to the right politically:

Most of the arguments in favor of dense urbanism come from people who are not actively raising families. You know why suburban sprawl happened? Because having a single-family home with a yard and easy car access to shopping, schools, and jobs is the ideal housing solution for families.

If you have a family with kids aged 2, 5, and 7, then mass transit is not terribly useful to you. You need to be able to transport small humans at odd and unpredictable hours.1

Do you know who almost never has time to do brunch, or people-watch at cafés, or stroll to interesting retail establishments?

Families.

My own view of the New Urbanism project is that it relies heavily on a mix of child-free 20- and 30-year-olds and well-to-do senior citizens. It has very little to offer people either actively engaged in raising children or cleaning up the economic aftermath of paying for college.

His footnote reads:

These tiny humans will cry and scream and fight. I suspect that most of the mass transit new urbanists would react to having young families relying on their subways and buses about the same as many childfree people react to the presence of babies on airplanes.

I think—I hope—that Last is mistaken here, and that a pretty good share of urbanists understand at least intellectually the necessity of accommodating families in their ideal urban places. I have no reason not to believe that, given the large number of people I follow who either have kids and are raising them in urban environments, or at least appear to understand the needs of families. Aside from transit being insufficiently frequent or nimble, one big issue is the relative absence of reasonably affordable family-size apartments in cities. I think—because it is difficult to raise kids in the city—that we don’t necessarily know whether or not people would like to do it.

The key for me is that we should not conflate the observation that “cities as they happen to be currently constituted in America today are often not great places to raise families” with “cities are not great places to raise families” or “classic urban environments are not great places to raise families.” The first is no doubt true in America. I do not believe the latter is.

When Last writes, “My own view of the New Urbanism project is that it relies heavily on a mix of child-free 20- and 30-year-olds and well-to-do senior citizens,” he’s right in a particular and immediate sense. But I don’t see how the broader, more abstract point that sometimes lurks underneath this kind of commentary—that human settlements as they have been built for nearly all of human history, even for most of American history, are inherently incompatible with the family—can possibly be right. That idea strikes me as something like a metaphysical error. Almost something like slipping from “fast food is bad for health” to “food is bad for health.”

I recount this because Last articulates the conventional view of American suburbanites very well, and I’m giving you my disagreement with that view in its extremity. But. There’s really no question that the parent/non-parent divide represents a huge experiential and philosophical gap in urbanism, or between urbanists and non-urbanists.

These questions of urbanism and kids, urbanism and parents, the parent/non-parent divide in how people think about transportation or the built environment or zoning or education or crime—these absolutely loom behind almost all of our discussions on these issues. And yet, for some reason, we rarely talk about them plainly.

I think it is probably true that a considerable number of urbanists do not really know what it feels like to be a parent: to be utterly responsible for another human being. This is not strange, really, because a lot of people in this policy area are young people who haven’t married or started families, and who are simply realizing how hard it has gotten to buy or rent a decent place close to work.

In some ways, they probably are realizing that some approximation of the college lifestyle—proximity to people, amenities, and professional opportunities—has become a luxury good. This is viewed by a lot of people as a kind of immaturity. I don’t think so. These are fine reasons to be an urbanist, and we absolutely should be building more housing in places where there’s already stuff. (You sometimes hear from older folks the idea that there’s something immature or dilettantish about walkability. You just want to walk to a bar. You think sitting in an overpriced coffee shop is the same thing as having a community. Real Americans drive. Etc. etc. Almost as if an absence of amenities is an amenity. Or almost as if self-denial is more important than complete neighborhoods.)

But the flipside of this is that a lot of these young urbanists have simply have not been in the position of, say, having to wonder whether their children will see something strange or uncomfortable or frightening on a city street or in a subway car, and then having to explain it in earshot of other people. They haven’t had to worry that their kid conspicuously pointing at someone or blurting out something inappropriate might spark an incident. Or what might happen if you get mugged when you’re with your kids.

I think of the times we went into New York City when I was a kid, and I was always tempted to point at someone yelling on the street, or go running, or what have you. New York City was in fine shape in the early-to-mid 2000s, but if it had been a little rougher, I might have seen people doing drugs in public, or other unsavory things. Of course it’s uncomfortable to have to explain those things to a child. This all changes the experience of being in a typical American city.

It’s easy to accept some risk of crime, for example, for yourself; harder to do it with, and regarding, a child. It’s easy to perceive the city’s problems as mere nuisances, whereas with, or for, a child, they may manifest themselves as menaces.

And when the same people cheering urban life are also skeptics of the police, or make fun of people who are uncomfortable seeing homelessness, or shrug at lunatics on the subway who turn every moment into a latent conflict, they’ve made your decision for you. (And not all of those people are the same people—here is one urbanist in Philadelphia who takes these concerns seriously.)

Parenthood is a categorically different way of existing in and perceiving the world, and a significant number of people my age and younger have no conception of what that feels like.

The preponderance of progressive, young, childless people in the broad urbanist movement almost certainly does lead to a blind spot on these matters.

I think you could boil all of this down to one observation: for some people—and not at all most, but probably some urbanists—the family is a special interest. Not only is the family not supreme in the landscape of policy considerations, but not even necessarily first among equals. Getting married and having children is no worthier a choice than putting ketchup on your hamburger. For people who believe that family life is hallowed, that children are a miracle and a gift from God—which is to say, lots of American Christians and right-leaners, people like Jonathan Last—the idea that their concerns are seen as akin to those of any other special interest lobby is almost offensive. At least, it can inspire a distrust.

You’ll see sometimes from progressive urbanists an opinion that goes like “Zoning reform is important especially for LGBT folks,” or a critique of single-family zoning as a policy to forcibly make the nuclear family normative. I don’t like to call this “culture war” or “making it political,” because these are real, concrete concerns for some people. They are, as far as I understand it, historically correct. And the people who make these arguments believe them and are making them to a potentially receptive audience on the left. (In other words, “Hey you left-NIMBYs, you care about LGBT people, don’t you? Then you should support more housing!”)

But when conservatives see these arguments, many conclude that all this housing and zoning and urbanism stuff is just one arrow in the quiver of left-wing social policy. Every time I hear “cities are climate policy” I hear a conservative saying, “Oh, so that’s what this is all about.” And because conservatives and religious people are more likely to have larger families, you get a parent/non-parent divide that magnifies the left-right divide.

People who have a lot of kids, own a couple of big cars, live in a nice detached house in a nice neighborhood, go to church, really believe it—some urbanists will look at that whole thing as kind of weird. Not because they’re urbanists, and not because urban environments are inherently hostile to such people, but simply because American politics has “bundled” urbanism with the progressive left to a great extent.

It may be the case that parenthood in some respects makes you sound like a conservative. And it may be that some people will therefore look askance at parenthood before reconsidering their politics. You get this sense that some leftists don’t quite like the idea of the family because it makes people more conservative. Maybe, maybe not. But I do believe it’s true that having a family really does make it harder to be an urbanist. And that’s a challenge to urbanists, not a challenge to families.

One big element of this is the SUV question: families who feel they need a large car, both for safety in the event of a crash, and for room for their kids/carseats, their friends, stuff, etc. You see a lot of SUV-bashing among urbanists and pedestrian advocates: not surprisingly, because these cars are fuel inefficient, more likely to kill a pedestrian if they strike one, and have obviously triggered a car-size arms race in which people feel they need to buy an SUV for their own safety in the event of a crash.

This is one of those areas where our dependence on the car leads us to an awful zero-sum view of life and safety. The “safest” car for the occupant will almost always, by definition, be the most dangerous car for anyone else in a collision. You can see how parents might perceive a childless young person prattling on about oversized cars as effectively saying “Yeah, maybe your children should die.” That’s not what anybody thinks. But again, if being a parent makes it harder to embrace urbanist ideas, so much the worse for urbanist ideas. That’s where a conservative urbanist starts.

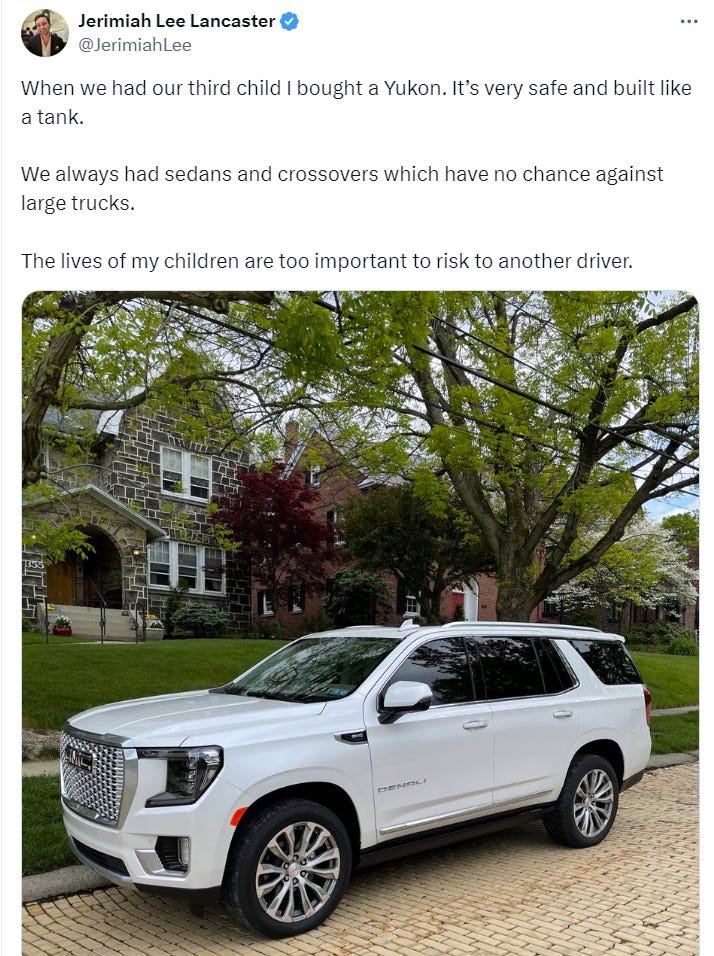

A few weeks ago on Twitter, a fellow shared that his family walked away from a severe traffic crash because they had a huge SUV. He basically, said, buy the biggest car you can afford, because your family is priceless.

Urbanist Twitter had a lot of fun with that, creating a series of memes making fun of it, which escalated from increasingly large and absurd land vehicles all the way to starships. Here’s one:

Now I know these people well enough to know what they mean: “Buying a bigger car and upping the ante in the arms race isn’t the solution to traffic deaths. Regulating or taxing large cars down to size, narrowing streets and slowing traffic, and shifting mode share from driving to walking, biking, and transit are.” I agree 100 percent with using regulation to break the arms race. I agree with all of that.

And I understand that part of the impulse to mock comes from a kind of cynicism or fear or experience. Those urbanists who have families and walk or bike or drive small cars know full well that their children are the collateral in the SUV owner’s safety. They’re not “being political,” which is how activist-y language feels to conservatives: they’re saying, in their own lingua franca, Your “safety” threatens our safety.

But I also get why someone who isn’t deeply familiar with urbanist ideas would instead be able to take no meaning from these memes except that these people think kids dying in car crashes is funny, or necessary for their ideals. Omelet, egg, etc.

Being a parent makes you defensive. When you have any sense that someone might be threatening your kids, you don’t listen to them. I don’t believe SUVs are “pro-family.” The idea that you need one for your kids—the other road users be damned—is a terrible idea. It doesn’t compute—it bakes misanthropy and violence into everyday life. (If you want a larger car, get a minivan. They’re better on all counts than SUVs except for the off-roading that only happens in commercials.)

But to mock someone for doing what they feel they need to do to keep their kids safe? There are only two words that deserves in response.

Here’s the original tweet. Does this seem worthy of so much mockery and snark?

I sometimes get the sense that the concerns and idiosyncrasies and needs of parents and young kids feel like inconveniences to others, even those who care about making our built environments and communities better for everyone. I get the feeling that in some quarters even the idea of starting a family is coded as “conservative.” This is all immensely misguided and tragic.

I don’t believe families are superior to singles or couples. I just believe their particular needs and feelings are real and legitimate, and an urbanism that views them or treats them as special interests is misguided.

As usual, Strong Towns manages to extract the ideas of urbanism and convey them without the tone and implied or inferred meaning of lefty Twitter urbanist discourse. Charles Marohn, the Strong Towns president, wrote of this kerfuffle:

My first daughter was born in August 2004. In October, a truck pulled out in front of me and I was unable to stop in time. My little Toyota Echo was totaled. It crumpled like a tin can, even though the force wasn't great enough to set off the airbags. I was the only one in my car.

I researched replacement vehicles and was pondering another Echo. When I shared that information with my wife, she shared some information with me: “If you get another tiny car, you won’t ever be taking our kid with you.” The message was clear. I bought a Honda Element SUV. (Those of you that read the last chapter of Confessions of a Recovering Engineer know how that turned out just two weeks later.)

Marohn, like me, is a right-leaning Catholic. He has kids, we don’t yet. That quote from his wife is basically what every American who doesn’t self-identify as an urbanist would think and feel. I don’t take that to mean that 99.9 percent of Americans should be laughed at and snarked at. I take it as an invitation to persuasion.

More Marohn:

While it is in any single driver’s interest to be protected with seatbelts and airbags, is it in the public's interest to have everyone protected in this way? The brilliant transportation planner Ben Hamilton-Bailey (sadly, no longer with us) once made the case to me that seatbelts should deactivate for the driver as soon as they enter an urban area as a way to make them more aware of the risk they transfer to others. He even suggested that a knife come out of the steering wheel, directed at the driver’s heart, to make clear what is at stake if they get into a crash.

Some zealous advocates reading that suggestion might find it brilliant. It is a brilliant insight, but Ben recognized, as most everyone reading this also recognizes, that it’s an absurd idea. As a society, we would never make driving more dangerous for the driver as a way to make things safer for those outside of the vehicle.

If you grasp that, you should grasp why making a fight against SUVs part of the culture wars is a dumb, ultimately losing, strategy. Dumb, dumb, super dumb.

What isn’t dumb? Let’s start with empathy. Everyone in this country has been touched by road violence. Every family has lost someone, or known someone close to them who has lost someone, in an automobile crash.

Perhaps my problem is that I can see every side of this. I can see how calling SUV hate a “culture war” feels like a dismissal of the carnage people who walk and bike face at the hands of these oversized vehicles. I can see how you could be radicalized to think maybe we do need a “war on cars.” I can also see putting my young child in an SUV and telling some moron on social media that he’ll pry that steering wheel out of my cold dead hands.

This is long, and maybe a bit jumbled, but it comes down to this: a normal reading of America is that the family is normative, and that the quirks and impulses of parents are fundamentally legitimate. It is urbanism which must, in this reality we inhabit, understand itself as a special interest. Though as this newsletter is basically all about, it should be a general interest.

But it’s not going to get there if it hectors regular people, tolerates petty crime, and treats the risks and dangers and discomforts of American roads and cities as opportunities to build character.

If it’s true that you go to war with the army you have, you also do public policy with the people you have.

Related Reading:

When Babies Grow Up, They Become Neighbors

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter, discounted just this week! You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

I kinda take issue with this whole premise. Urbanism, at least for me, isn't coffee shops and brunch - it's libraries, grocers, schools, karate, baseball and swim class all being a short walk away. Driving 15 minutes to a Walgreens isn't a convenient lifestyle. This line, "If you have a family with kids aged 2, 5, and 7, then mass transit is not terribly useful to you" feels incredibly patronizing. It actually IS useful to me to come to work. Taking the bus and the train ARE useful and you DO see kids on them regularly. The issue is frequent service. But it's true, I don't want that to be the main way my kids get around - i prefer if they walked.

I think advocates who push back on the idea that families can be urbanist also lack empathy. The idea that kids have to be shuttled everywhere as the only reality is also not how suburbs were originally designed, and not how most suburbanites grew up. What they are advocating for - essentially raising a kid who is trapped in a car between manicured activities - is both a response to the dangers of fast cars bounding neighborhoods devoid of stimulation and also an elitist change to the way they themselves were raised. Kids should be able to walk and bike safely and independent of their parents. Three kids used to comfortably fit in a station wagon, but cars are too dangerous so even inside that's not enough now. But necessitating purchase of an expensive minivan to have a large family is elitist. Just like housing is expensive, anti urbanists are unintentionally making it even more pricey to raise a family. Why is family becoming less universal to Americans? Because we are making it so expensive and exclusive.

I think suburbs and cars /might/ be the easiest way to wrangle a couple of infants/toddlers around. But as soon as those kids are approaching adolescence and gain any degree of independence, car-dependency makes them dependent on being driven around town by parents, while walkability and transit allows them to take care of their own transportation needs.