Awhile ago I wrote in my drafts, “Progressives talk about crime the way conservatives talk about housing.”

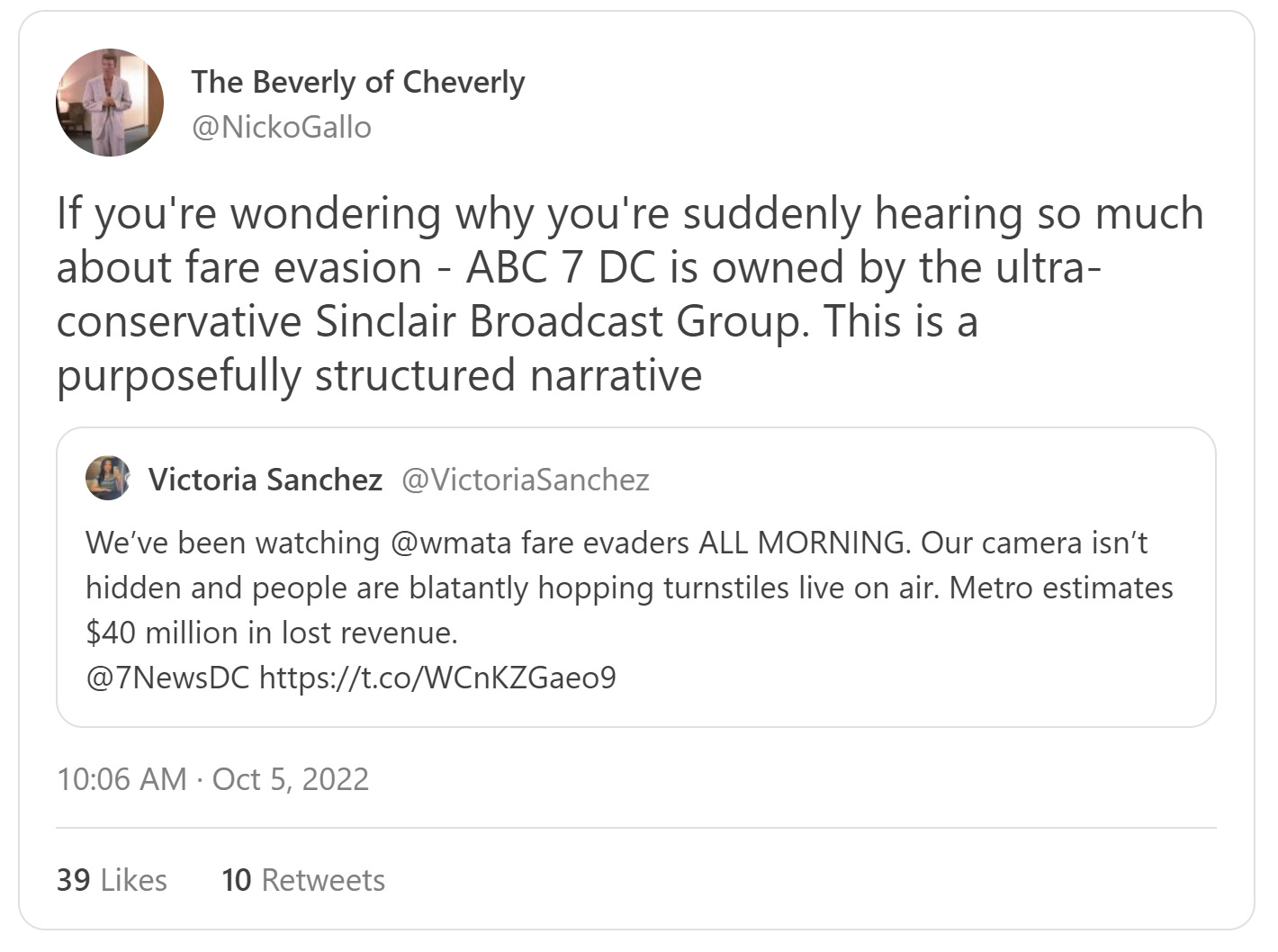

Then I saw two things online. First this, and dozens of other tweets like it, on fare evasion, and an announced crackdown from WMATA, which runs the D.C. Metro:

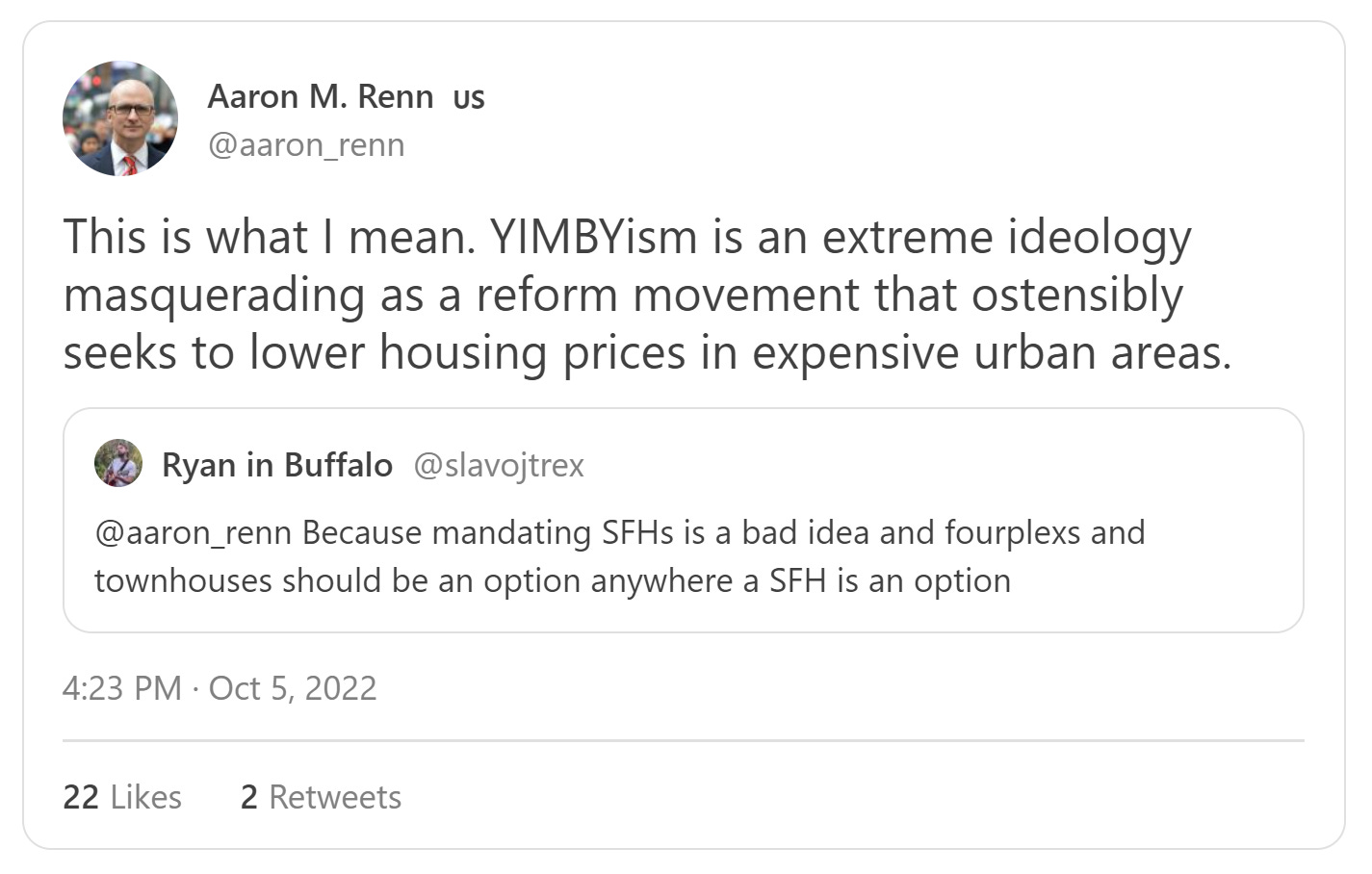

Then this:

Is fare evasion a real problem?

Are YIMBYs ideological extremists?

Answer the second question first.

Aaron Renn, who once blogged under the name “The Urbanophile,” is a Midwestern conservative urbanist and cultural commentator. He’s an interesting, quirky fellow. I’ve been compared to him once or twice. I did not and do not agree with everything he writes, but the broader the urbanist coalition, the more hopeful I am that we’re on to something. I imagine Renn is a bit like this man I ran into at a recent event:

I ran into an older fellow, a self-styled conservative urbanist, with whom I chatted for awhile. Some of his opinions certainly diverged from most of the rest of the crowd. But when he mentioned “National Airport,” I was a little incredulous. “A conservative who doesn’t call it Reagan Airport?” “I don’t believe in renaming things,” he said. “It’s the Redskins. And it’s National.”

He also loved trains, and he proffered that he couldn’t care less whether an apartment building went up on his block. “It’s not my property, it’s none of my business,” he said. I can get behind that.

So it was disappointing to see Renn suggesting that YIMBYs hold an “extreme ideology.” It was even more disappointing to see him argue, without evidence, that YIMBYs want to “demolish your neighborhood.”

He followed these thoughts up with a full article. But ultimately, he doesn’t really articulate why he objects to duplexes or fourplexes in small towns or suburbs, at least not in a way that gets past abstraction (he cites a tradition of localism in American land use.) Mostly, he casts the moderate rollback of a blanket government ban on every housing option except the single-family detached home as radical. He makes it appear as though YIMBYs are choosing to die on the hill of fourplexes in the exurbs, when he is the one who has arbitrarily chosen that hill. He largely leaves the reader to speculate what his actual objection might be.

Well, I’ll give it a shot.

I do not think Renn is winking at racism or racial exclusion. More likely is that he views the issue in a way that I and many urbanists would consider a fundamental misunderstanding. Ultimately, for many people, the notion of the detached single-family house as the Platonic form of the American home is so strong that they are invincibly ignorant as to the possibilities that that ideal forecloses—and even to the fact that there are any other possibilities. It is impossible for them to believe that anything more than a radical minority would want any other possibilities.

But whatever Renn’s motivations, you cannot ignore the racial elephant in the room. All that talk about zoning being racist, segregationist, exclusionary—how true is it? A lot of people will never even stop and wonder, assuming that all such claims (save for slavery or Jim Crow itself) are overblown. All that many conservatives need to know to judge the veracity of these claims is that it is usually liberals who are making them.

The word you want to choose is up to you, but as far as I can tell—and I can assure you that I do not like to say this—these critiques of zoning are more or less true. Exclusion was baked into the zoning cake from the very beginning, back to the Supreme Court decision finding zoning constitutional under the state’s police power, and which referred to apartments (and, by winking extension, the people who live in them) as “mere parasites.”

Many historians, in fact, argue that modern zoning grew in part out of (SCOTUS-prohibited) racial zoning: codes that explicitly zoned land by race. Because racial and economic inequality largely overlap in America, you could reverse-engineer racial zoning in a seemingly technocratic, neutral manner by effectively zoning by income.

If you, like me, grew up in a Republican home, and thought America was more or less good, this can be difficult. It means that most municipalities, and a non-negligible number if not a majority of ordinary, median Americans, effectively support a form of segregation today: racial, economic, all of the above. C.S. Lewis famously said he was “dragged kicking and screaming” into Christianity. In some ways, that’s how I feel about becoming an urbanist.

At the very least, I now find it impossible to deny that zoning largely functions as a crude, suboptimal insurance scheme for affluent homeowners. Insurance in terms of property values, by limiting supply, and in terms of eliminating crime in the neighborhood by eliminating the socioeconomic strata from which many criminals come. It works—in the sense that burning down your house to kill a fly works. I elaborated on this in no less a conservative publication than The New Atlantis:

Suburban car drivers sometimes reject transit for more troublesome reasons, worrying that the expansion of urban transit will also mean an expansion of (by their reckoning) the wrong kinds of people into their neighborhoods — the homeless, criminals, or simply minorities. As a 2015 Slate piece reported, a largely white suburb near Dayton, Ohio long resisted a bus route implemented to help many minority workers reach their jobs at a mall. To accommodate the bus route, the suburb’s city council asked to add police call boxes and surveillance cameras at bus stops. By this logic, limited freedom of movement for those without cars is a kind of insurance against them having access to suburban neighborhoods.

How do you carry that? What do you do with that? It’s a wrench into how you want to see your country. Doubtless it is the same for most of those people themselves, few of whom are personally racists. But to acknowledge the troublesome history of zoning can feel like an admission of guilt. And admitting guilt in such an overheated political moment as ours can feel like painting a target on your back.

So people will downplay that history, or they will ignore it, or they will disagree by agreeing. Well, if wanting a nice house in a safe neighborhood for my kids makes me a racist, count me in.

That New Atlantis passage was about transit, but transportation and land use are practically one in the same issue. So, of course, are schools. The same bitter, deeply emotional arguments play out there too.

What do you say to a parent who, for no conscious reason other than selfless love of her child, rails against, say, school redistricting? Don’t you dare put my kid in harm’s way for the sake of your social engineering scheme, she might say, imagining the arrival of fights, drugs, gang interdiction programs, and ESL programs, which in her mind might all be of a piece. (She might very well be in Montgomery County, Maryland, and she might very well vote Democrat.)

The fact is that de-concentrating poverty, and giving the poorest and most marginalized children a peek at the broader world of possibilities, actually makes them better off, without hurting anybody else. Being poor doesn’t make you a criminal. Concentrating poverty, walling it off, pretending it goes away by turning your back on it, like a cat who thinks he can’t be seen because his head is behind the curtain—that is how crime arises. But that doesn’t mean very much to someone who will do absolutely anything to protect her child against ills real and imagined, who only hears you saying, We are willing to sacrifice your child for the sake of someone else’s.

I do not like writing any of this. It is personally difficult, and it feels professionally risky. Most urbanists sort of shy away from it.

And I guess that brings me to crime.

What do I mean by “Progressives talk about crime the way conservatives talk about housing?” What I mean is that housing is an abstract issue for a lot of conservatives. They view it through a very remote lens, without really grasping how urgent it is. They reduce what is obviously a problem of public interest to a problem of every individual person’s preferences:

The city isn’t wrong for shackling the housing market; you’re wrong for wanting to live in the city.

Look who wants a nice house handed to them.

In my day we took what we could get and we were grateful for it.

Maybe if you stopped buying soy chai lattes every day you could buy a house by now.

What does that have to do with crime? I often detect the same smirking, cavalier attitude in the way that some progressives dismiss concern about crime.

You’re just a scaredy-cat suburbanite.

Sure, X is a problem, but Y is a bigger problem, and besides, look at you getting away with Z.

Teenagers always do silly things, what would you do, put them in jail?

If we institutionalize even the smallest minority of severely mentally ill homeless people, it’s a slippery slope to endlessly hassling all homeless people.

You can probably think of more examples.

Why the resistance to talking frankly about crime? Not exaggerating it, as many on the right do, but simply acknowledging that it’s a legitimate concern, including, of course, for poor people and people of color?

With the fare evasion issue, I understand that it is true, as a practical matter, that enforcement capacity is limited. That hassling people and pushing them into the criminal justice system for very minor offenses is counterproductive. It may be the case that, as a bunch of folks commented, WMATA and the D.C. police have “bigger fish to fry” than fare evasion.

But I guess I’m enough of a conservative that I dislike the idea of the rules being optional. If there’s no fare, make it free, not optional. “Law and order” may be a slogan and an abstraction itself, and it may come down unfairly on the most marginalized. But that does not mean there is no such thing as law or as order.

As I’ve carved out this space for myself as a right-leaning urbanist, I’ve increasingly understood something, and I’m not sure how to deal with it. There is no question that poor management of America’s urban problems, and a cavalier view of crime and disorder in particular, is a factor in the stories that conservatives tell themselves about cities. I grew up hearing these stories. The idea that density somehow spawns crime, like the land-use version of the old notion that rotting meat generates maggots, is almost an article of faith for many people. Suburbia is understood as a form of insurance against the inherent problems of the city. Some of this is rooted in racism, and much of it is rooted in ignorance. But it is not rooted in nothing.

Every time I hear some version of this narrative, I see a fellow on Twitter confirming it, in a way, from the other side: downplaying “low-level” crime, arguing that the police have “bigger fish to fry,” making fun of “scaredy-cat suburbanites.”

I want cities to thrive, as do all urbanists, and most Americans. But some people talk as if they don’t.

I am not a “carceral urbanist” (I wince at the phrase itself). I do not dream of throwing the teens jumping the fare gates into a police van. I understand that crime has social and economic causes, and that if any of this were simple of easy, we would already have figured it out.

I’ve merely shared my thoughts on a few issues that make it tricky to be a conservative urbanist. And now it’s your turn to tell me what you think.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 400 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Thank you for this really thoughtful piece, Addison. You're one of the most consistently interesting writers I read, because you're able to write about contentious issues in a way that transcends the usual partisan talking points.

This piece fits in well with the guest post from Luca Gattoni-Celli last week, in which he argued that YIMBYs need to think more seriously about solutions to the problems faced by urban communities if they're going to get NIMBYs to get more comfortable with increased density. If you're trying to win over people to your cause, instead of just scoring points in a never-ending culture war, you can't just blow off their concerns. Progressives who try to write off concerns about crime as paranoid or racist, or conservatives who try to write off concerns about housing as millennial entitlement, aren't engaging seriously with the issue. It's hard enough to discuss solutions to these challenging problems without one side refusing to acknowledge that the problem even exists.

It's been an interesting time talking to people about urbanism and city planning, especially to my suburban friends and family. By and large they don't even know of any options other than single family homes or tiny cracker box apartment 100 stories high.

Talking about the "missing middle" has proved slightly fruitful because gentle density that is beautiful is an easier idea to swallow than ugly, brutalistic, soviet-style blocks.

I've also confused some people when I say I'm an advocate for densifying some places - or even just making it legal to possibly build with any density - because they associate density with radical leftists. I'm a right-leaning man from a right-leaning family and the only proponents for density they've ever heard from are indeed radical leftists, so hearing that from someone they consider conservative is difficult to hear.

Right leaning urbansist have a lot of ground to cover to convince people that good urbanism does not inherently entail crime, disease, and poverty. My belief is similar to yours, Addison, it is just that so many people are "invincibly ignorant" to the point they cannot fathom any form of urbanism as being consistent with their politics or desired life.

It can be done, though! We've just got to inform people that there are other ways of building that are good and conducive to human flourishing.