"Why Don't You Just Move?"

Every region must accommodate a broad cross section of the country’s people

Recently The American Conservative published this article, titled “It’s Not a Housing Shortage.” The author’s argument, such as it is, amounts to the fact that in some places—she prominently cites Ohio and Oklahoma—it is possible to find very cheap houses. She recounts that she and her husband recently moved to an “economically depressed market” and bought a century-old house that needed some work, after several years of pinching pennies.

You do you, but people drastically underestimate what it can cost to restore and maintain an old house. Less posh neighborhood? Fine. Fixer-upper full of hidden and deferred maintenance? It’s just not reasonable to expect an ordinary couple to take on that workload in order to have a roof over their heads.

But underneath what at first sounds like a clear-eyed, practical argument—like it or not, you can only buy what you can afford—is a deeply ideological argument, and one which I also doubt on the facts:

With the rise of social media and online journalism, key housing markets have become trendy in a way they never could have before. A classified ad now has a national audience, and bougie neighborhoods a ream of TikTok viewers. People are moving to areas they have no connection to and no relatives near because they saw it online and thought it looked cool. I know a few. This has the effect of driving up prices in areas that otherwise would never have known such demand.

In other words, the author—along with a lot of people, to be fair—seems to think that cities are just trendy and expensive for no particular reason at all. Silicon Valley or Northern Virginia, in this view, are crushingly popular markets for the same sort of reason that every five-year-old wanted a fidget spinner a few years ago. It’s as if the fundamental economics underlying metro-area economies do not exist.

The reality is that most of what makes a place “desirable” is not its amenities per se, but its productivity—which is to say its economy and its job market. “Nice” places are not nice because they are a reward for high-earning, hardworking people. They’re “nice” because they have strong economies, and places with strong economies can support excellent schools, parks, transit, road maintenance, restaurants, and everything else that people value.

If this is an argument for anything to do with Oklahoma, it’s for finding a way to bring economic growth to places that have been left behind or hollowed out—not for moving there for the prices and hoping everything else follows.

But there’s another problem in that paragraph. “People are moving to areas they have no connection to and no relatives near because they saw it online,” the author writes. In her view, America’s housing problem is mostly young people overwhelming the housing stock of a few key, trendy markets. There is a grain of truth to this, maybe, but 1) the solution is still to build more housing in those places, and 2) our housing problem runs the other way too.

Every housing advocate I know has friends who were pushed out of the D.C. area because of the region’s housing crunch. These are people who have put down roots, raised families—even in some cases people who grew up here. They desperately want to stay, and they are leaving against their will, because an entire metro region increasingly cannot accommodate people of modest incomes anymore.

People are being pulled away from places they love, and forced out to the edges of the region, or out of it altogether. A huge driver of exurban sprawl in the outlying rural counties is the housing crisis closer to the core. And there is a deep irony here: the people in those rural counties don’t like this trend either. You start by telling people to stay rooted, and you end by forcing them to parachute into places they do not want to be, among people who do not want them to be there.

I wrote about this back in September:

One member told us about a couple his family is friends with. They had to leave Northern Virginia and ended up all the way in Southern Maryland. (That’s not a generic term with malleable borders, like North Jersey; it’s the southernmost mainland region of the state, out along the Chesapeake.) It probably shouldn’t be part of the D.C. area, but our housing crunch has pulled it into that orbit. You pretty much have to drive everywhere there. There’s not all that much to do. Local old-timers don’t like the influx of urbanites. Urbanites don’t want to get pushed all the way out there. Local housing policy closer to the core forces these outcomes nobody wants.

Another member who lives in D.C. was facing an untenable rent hike and was considering throwing in the towel: looking for some place in West Virginia or Pennsylvania, somewhere where the prices finally go down a level or two.

These two stories arose out of a gathering of maybe 20 people. There are dozens, hundreds more like it.

Sometimes people will ask my wife and I—here in Northern Virginia, watching houses creep down from $800,000 to $750,000 while interest rates double—why we don’t just move.

It’s a funny thing. Usually “just move” is directed at poor people, in disinvested places. In early 2016, Kevin Williamson at the conservative magazine National Review wrote that the white working class needed not Donald Trump but U-Haul.

Williamson wrote, rather infamously:

So the gypsum business in Garbutt ain’t what it used to be. There is more to life in the 21st century than wallboard and cheap sentimentality about how the Man closed the factories down.

The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die. Economically, they are negative assets. Morally, they are indefensible. Forget all your cheap theatrical Bruce Springsteen crap. Forget your sanctimony about struggling Rust Belt factory towns and your conspiracy theories about the wily Orientals stealing our jobs. Forget your goddamned gypsum, and, if he has a problem with that, forget Ed Burke, too.

This is the attitude, by no means limited to one political alignment, that Chris Arnade argues against in his 2019 book Dignity. He focuses on what he calls the “back row”—the people (of any race) who are not highly educated, ambitious, and upwardly mobile. They value things that our society generally devalues in subtle ways: their faith, their families, their hometowns. They are not able, or they have no desire, to leave the only places and people they know to look for a high-tech job.

Now I don’t have any particular commitment to the idea of “staying rooted in your place,” i.e. a sort of ideology of localism, which I critiqued rather strongly here. Sometimes moving is great, and you can’t blame people for seeking opportunity. But “let them rent a U-Haul” can sometimes sound a little too much like “let them eat cake.” Especially when the housing prices in those places they’re supposed to go are off the charts!

But as I said at the top here, most of this discourse focuses on the working class in left-behind places. It is interesting to face the same question as a highly educated person who in many ways is closer to the “elite” than the working class. When we tell people in the left-behind places to rent a U-Haul, what we mean is, “Go seek opportunity.”

When we tell young professionals to just move, we are telling them to leave opportunity.

Now I should be clear that there are plenty of places worth living in, and that are probably lovely and quite nice and have good job markets, outside of the handful of top metro areas. For example, check out this interesting piece from Vox, by a young woman who left Seattle for Cedar Rapids:

I’m paying $650 a month for a gorgeous studio with a view of the Cedar River and in-unit laundry. I’m the first tenant to occupy this apartment (and the first tenant to use its brand new appliances). Considering that my first Seattle apartment was a converted hotel room with no kitchen and a landlord who advised me to wash my dishes in a bus tub and dump the dishwater into the toilet — WHICH I DID, EVERY DAY — living in this apartment feels like living in another world.

But the irony here is that even a lot of places that feel remote to someone like me—the second-tier or even third-tier metros, or smaller cities or towns—are experiencing their own housing crunches. Everybody knows that San Francisco is unaffordable. Here’s the housing price index for Altoona, Pennsylvania:

When timeworn, sleepy, small-town America has a price chart like that, you have a housing crisis. And as noted above, a major driver of this national crisis is the most desirable metro areas refusing to accommodate growth, and pushing it ever outward.

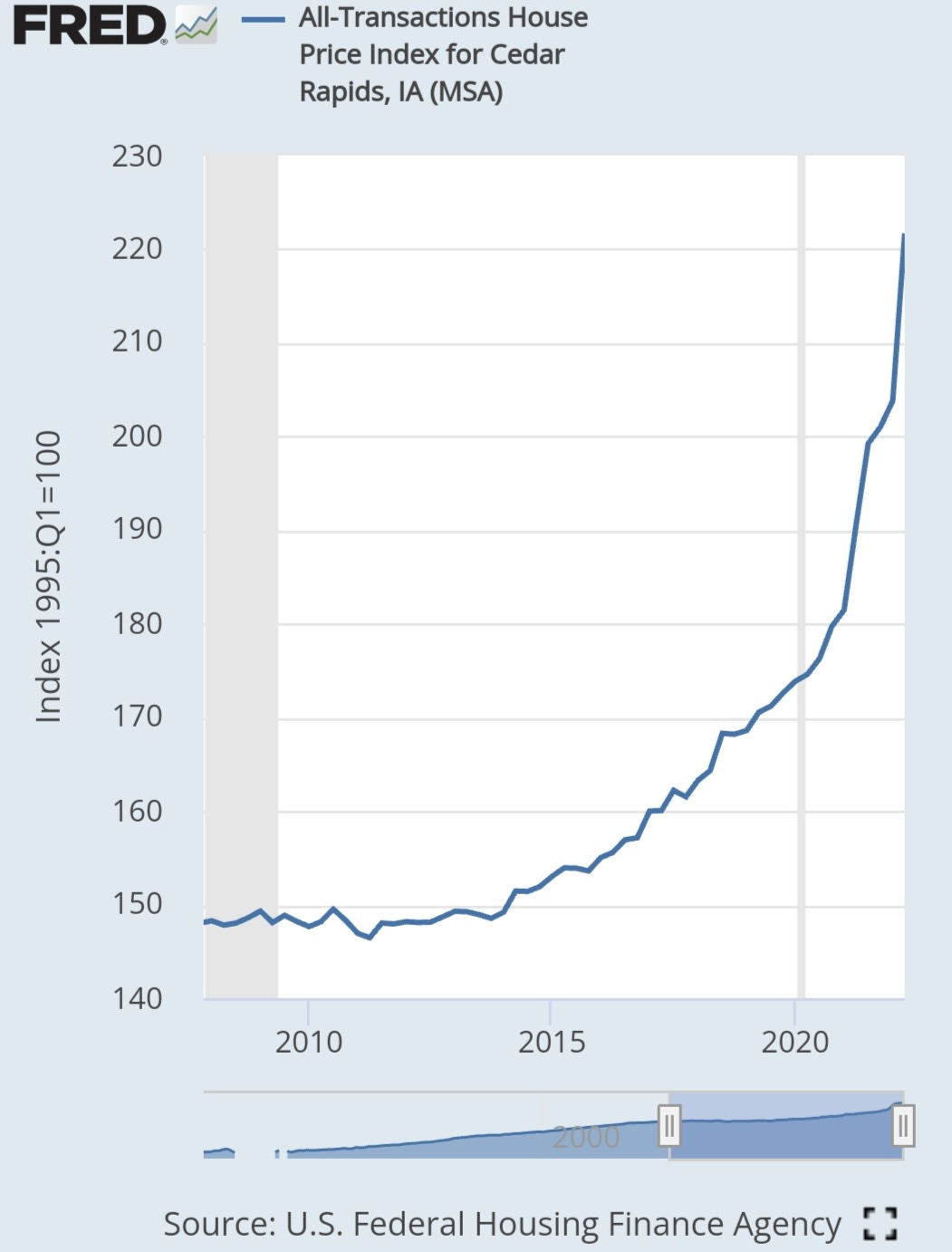

Oh, and here’s Cedar Rapids:

I’ve talked before, here and here, about the idea that there isn’t really a housing crisis, and relatedly, the notion that there’s no real material basis for the late development, as it were, of America’s youngest generations. Many people simply blame their priorities.

If you really wanted to get married/own a home/have kids/etc., you’d make different financial and lifestyle choices: No nice appliances or consumer goods, no international vacations, no eating out, no expensive cars (I agree with that one).

And, maybe you should just move somewhere more affordable. Sure, Fairfax is nice. But ever hear of Hagerstown?

First of all, asking people to forego all of the consumer luxuries that the same people tout as the benefits of capitalism is a little hypocritical. Nobody is stuck in a tiny apartment because they bought a “nice flat screen TV” (as if there’s any other kind of TV on the market these days.) I found a house in Fairfax County the other day selling in the low $800s. I found a sale record from the 1980s, and adjusted the sale price for inflation: $400,000. Double the cost of inflation. Should the East Germans have just worked harder so they could buy more than old cabbage at the grocery store?

All of the things that my generation is chided for buying are getting cheaper—through markets!—while housing, one of the few areas where this country effectively practices central planning, is ballooning far faster than inflation. Buy your avocado toast or forego it, but every day it becomes a more infinitesimal fraction of your down payment. If you can ever scrape one together.

But beyond all of this, there’s something really deeply weird and almost terrible about the idea that whether or not you want to start a family dictates which part of the country you end up in. Telling some people to just move to find decent jobs (in cities they can’t afford?) while telling other people to just move to some place with low cost of living (what about jobs and amenities?) is a recipe for a broken country. For a country increasingly riven by ideological and geographic polarization.

“Oh, Fairfax. You must be one of those childless pod people. How are the crickets tasting?”

“Oh, Hagerstown. You have a big family. Maybe you homeschool too!”

I’m not knocking homeschooling. I was homeschooled. I liked it. I’m not even knocking eating insects, if that’s your thing, but it’s not mine. The point is that when geography dictates politics and culture, all of this culture war stuff will get worse. This is the country we will make for ourselves if we continue to deny our housing crisis. It is a recipe for madness.

All of this, in other words, is a problem of collective, national importance. It’s a terrible thing for our country—politically, economically, culturally—to have entire cities or regions where you go to be an ambitious careerist, and others where you go if you want to start a family. Every region needs to accommodate a broad cross section of the country’s people.

And I guess that’s why I won’t “just move.” As long as our finances make it possible, I will not be part of the further fracturing of our country’s civic life. I will not uproot myself from the place my wife and I have determined to call home. And I promise that if we ever get into a nice house, which we would indeed like one day, I will fight like hell for the right of myself and my neighbors to build and do more with that land, now or one day, so that planning decisions from half a century ago do not squeeze out the vitality that makes this place great.

It’s a housing shortage.

Related Reading:

Apartments, Ownership, and Responsibility

Still Renting After All These Years

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 400 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Oh this is crazy. YOU DO RENOVATIONS....That's your "thing". For 99% of the population, that is not the case. One of the biggest issues I see is with people desperate to get out of the overpriced rental market biting off more then they can chew. Most people don't even have the knowledge base to find the contractors they need that won't take them to the cleaners.

It is wildly unrealistic to expect everyone to be able to do what YOU THINK they should be able to do because it's something YOU HAPPEN TO DO.

For example, I was a molecular biologist for many years. I had almost a decade of post-graduate education to get there. What if I suddenly said everyone should be able to do what I did? You would rightly think that I was crazy. It takes a lot of time and skill to do what I did. The same is true for renovation. Like molecular biology, home renovation is a complex. They are not error-friendly fields. Anyone not knowing what they are doing could blow up a lab. Anyone not knowing what they are doing could cause cause tremendous damage to a house, like start a fire. In neither case can you can't just pick up a book and learn it. With a home renovation you have the added burden of living in a construction zone for months on end. At least I could get away from the lab when I went home!

You also have to recognize that most people who are married with kids are spread very thing. Many families need 2 adults working well over 40 hours a week each to make ends meet. And many employers demand unpaid overtime as well. Then they have to take care of their kids and many also have parents to care for as well.

There are a few people this can work for. A VERY FEW.

More housing supply is needed to bring down prices, but this is often opposed by local residents motivated by the same resistance to change with which you seem to sympathize. Should we tell the NIMBYs to "just move" if they don't like new housing?