It’s hard to believe it, but 2022 is only the first full year I’ve been writing this newsletter. I’ve written every single day (except Sundays) since I started back on April 6, 2021. I’m approaching 600 pieces in the archive. And I’m not about to stop.

I’m at the point now, having written probably hundreds of thousands of words, where I sometimes remember an idea or a line, but can’t recall which piece it appeared in. And if I’ve said the same thing twice, it’s most likely because I didn’t remember saying it the first time!

In last year’s roundup, I wrote briefly about our calm, stay-at-home New Year’s Eves. That isn’t changing tomorrow night, but it is our first new Year’s Eve in our new house, and we just finished hosting our first Christmas. The only thing missing is a roaring fire (we have a fireplace, but we were advised to have it inspected before using it, and we haven’t gotten to that.)

I’m thankful for all of that, and also for your readership here. Hard numbers are a trade secret, but I can tell you some of these pieces do better numbers than pieces I publish in actual magazines. And I think that’s pretty cool.

I’ll be starting with most-read and going down to 10th most-read. Thank you, as always, for reading!

#1: Didn’t Used To Be a Pizza Hut, February 2

I had a feeling this illustrated deep-dive history of a commercial building in Maryland’s D.C. suburbs would do well. But I really had no idea that it would become my most-read newsletter piece ever by a very wide margin. It got a lot of play on social media and online, earned me an interview in the Washington Post, and got reprinted recently at Greater Greater Washington.

It’s possibly the most fun I’ve ever had putting a piece together too. And the result of a really simple question—“what did this building used to be?”—turned out to unearth a largely forgotten piece of Maryland history.

Give it a read!

#2: First Impressions, Raleigh/Durham, August 16

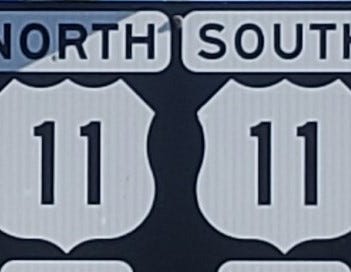

This piece did the rounds among urbanists in the Raleigh/Durham/Chapel Hill area, known as the Triangle. I was writing about the region’s highly car-dependent, spread-out development, as opposed to its older core cities, which are quite nice. This part of North Carolina has been growing rapidly for decades, and it’s an interesting example of some of the newer preferences in urban planning clashing with overall suburban land use. There are lots of attempts at denser housing or mixed-use development, for example, but transportation heavily favors driving. This creates a lot of disconnected quasi-urban islands.

It’s interesting to compare to the D.C. area, which has much more public transit, and more of a sense of planning and order. Despite being built in such a sprawling pattern, however, many find the Triangle to be relatively good compared to other suburban boomtown regions.

#3, “Why Don’t You Just Move?,” October 24

I wrote this piece as a sort of fourth part to an unofficial four-part series on a lot of the more abstract questions that inform housing discourse. (Here, here, and here are the first three.)

In this one, I focused on the idea that if you’re priced out of a /city/region/metro area, you should just look somewhere else. I argue that that’s no way to organize an economy or society. Cities aren’t expensive because they’re “nice”; they’re expensive because they have a lot of opportunity—that is, a strong economy—which supports nice things. It’s zero-sum thinking to treat that opportunity as something that is diluted, rather than enhanced, by fixing housing markets so more people can access it.

Furthermore, I pointed out that the end point of “just move” is that our country becomes overlappingly sorted by politics, class, family structure, etc. Fundamentally, unaffordable housing costs are not a personal obstacle for individuals to navigate, but a social problem of collective importance.

#4, Still Renting After All These Years, January 17

This is another piece from my unofficial four-part series. I work with the common notion that hardship is an opportunity to build character, rather than a problem to be solved. There’s really a lot here, and pieces like this are the core of my newsletter, so I won’t say too much. But here’s a little snippet:

Some people—often conservatives, but not always—argue that if we really wanted to own a home and raise a family, we’d find a way to make it work. As I’ve acknowledged, perhaps, in some cases this is true. But it requires one to exert great willpower, to effectively refuse the cornucopia of consumer delights which the same people in other contexts cite as the wonders of capitalism. Televisions are 20 times cheaper than in 1950! How dare you buy one!

Moreover, this view endorses a notion that entirely unnecessary hardship is a good thing: an opportunity to build character. It seems to equate ordering society to make doing the right easier to a handout or a welfare program.

#5, What Housing Crisis?, March 7

I wrote this after a friend and I visited Gaithersburg, Maryland, where a lot of Montgomery County’s new development is. We walked around a big new development, with a mixed-use town center featuring stores and apartment buildings, and surrounding neighborhoods of townhomes and detached houses. It looks like a lot of housing. And yet, in the scheme of things, it isn’t really much at all. So I wrote about how we can pick up the impression that we’re building so much, when in reality we really aren’t even building enough.

#6, The Opposite of Home Improvement, November 15

Usually I have an inkling when a piece is going to do really well. I did not expect this short piece about how I love Formica counters and old appliances to be in my top 10 for the year. But I guess everyone has an opinion about home décor and design, and so this got shared quite a bit and sparked a lot of comments too. It’s a fun, light read.

#7, More on Pro-Family Urbanism, June 22

One of my recurring arguments here is that cities and towns—as opposed to suburbs—are and should be good places to raise a family. There is nothing inevitable about the impression, and to some extent reality, that you enjoy the city while you’re young and single, then get married, have kids, and move to the suburbs.

The key in this piece is that car-dependent land use imposes a particular inconvenience on parents, and on children. Every trip anywhere involves strapping the kid into the car seat. When they’re older, they’re trapped at home until they get a license. There’s really nothing family-friendly about isolating people like this.

#8, The End of Lancaster’s Family-Style Dining, March 24

Without much fanfare or notice outside of the local area, the all-you-can-eat family-style restaurants in Lancaster have disappeared. There are still “smorgasbords,” i.e. buffets, but the iconic restaurants that sat strangers at long tables together and brought out giant trays of food to share appear to be all gone.

I did some searching and didn’t find anything outside of the immediate Lancaster area remarking on this. It’s really neat and rewarding to occasionally publish stuff here that presents new information or breaks a story.

#9, The Menace of Cars, October 27

As with housing, I think about the psychology of driving, and the broader questions that inform policies and attitudes. I was thinking about why people get so angry and defensive in their cars, and what driving actually does to us, psychically. Here’s a bit I think is very interesting and foreboding:

What does it do to your character, and to your mind, to accept the fact that there is a good chance you will kill another human being simply in the course of running your errands? Once you accept that a toll of 30,000 to 40,000 people is normal and acceptable, what else are you accepting or allowing yourself to accept? Does it erode our moral integrity to assent to that? To feel, and to know, that in some way our freedom of movement demands a death toll?

#10, Is Zoning a Contract?, January 13

Zoning creates the idea that there are and should be entire places that should look and feel a certain way forever. This is the crux of the problem. That isn’t how neighborhoods or communities or cities grow. The expectation that you’re “buying a neighborhood,” and that the bargain includes the right to freeze in time every aspect of the whole place, flies in the face of how we build truly great places. If we took this approach from the beginning, we would never have built most of the places Americans now love: places we love but can’t imagine building today.

Check out the whole piece, and that’s a wrap!

Honorable Mentions:

AD Who?

The Ice House

Housing and Deservingness

Suburbia Was a Housing Program

The Last Buffet, Or The First New One?

Related Reading:

The Deleted Scenes Top 10 of 2021

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 500 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

I'm grateful for your writing in 2022!

I found you through Jake Meador sharing your piece "Still Renting After All These Years" - and since then have *especially* enjoyed your posts at the intersection of urban design/policy and family life/children (parent of 3 tiny boys, here!)