The other day I saw this tweet from Nolan Gray:

Now, 60,000 in five years in a huge state isn’t transformative. But it’s not nothing. It’s certainly not a negligible number. Building an ADU is a new thing for most homeowners, not something they’re familiar with, whether it’s how to actually build it, how to finance it, how to be landlord, etc.

Many thousands of people must have looked into it seriously or semi-seriously and decided not to move forward. Many more must have thought about it. The universe of people, from curious to committed, is much larger than the number of permits actually issued.

I emphasize this because, when I bring up things like ADU ordinances, or modest zoning reforms allowing a second home on a lot or splitting a single-family detached house into a duplex, I get one answer the most. It goes something like this:

“The only thing that will happen is that developers will buy up and destroy single-family houses, and we’ll all be forced to live in tiny rentals. No homeowner wants to be bothered splitting their house into a duplex, or building an ADU. Nobody wants to become a small-time landlord.”

Well, except the tens of thousands who do.

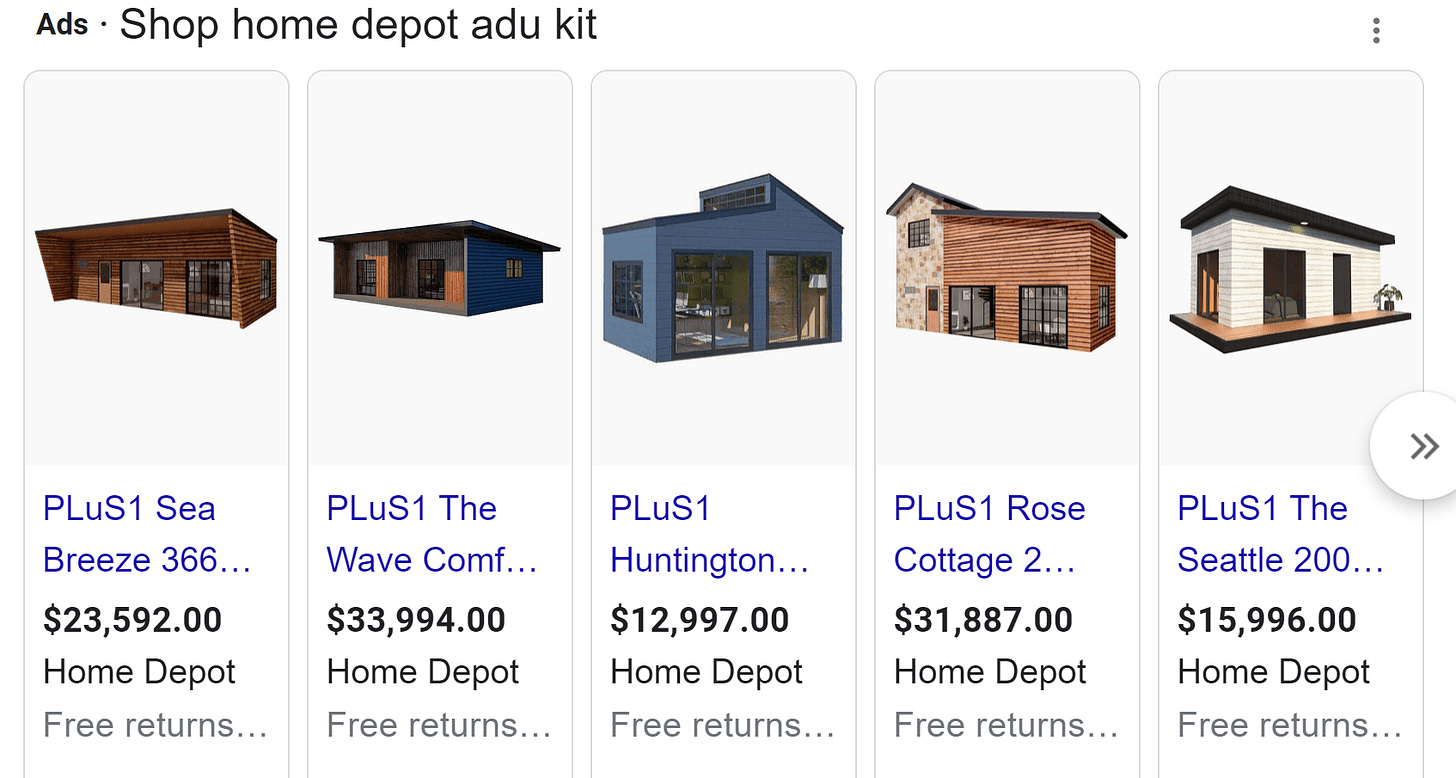

Home Depot even sells prefab ADU kits!

How freaking cool is that? I see a little bit of entrepreneurship and creativity being permitted once again, after a long interlude of what amounts to central planning on housing and land use. I think of diners and motels and filling stations, which anybody a century ago could buy a kit or template for, get to work, and go into business. Damn does our country need that spirit again, and a regulatory regime that doesn’t view it as a nuisance or a sparing favor, but as the backbone of building places.

As things like ADUs and other small-scale development projects become more common, they will only become easier to do. There’s learning by doing, building a body of knowledge and best practices. The financing also gets easier, as banks become more familiar with the standard economics of these projects. (Financing, separate from zoning, is a major barrier to small projects. But zoning is a factor, in that it makes such projects less common and harder for the bank to evaluate. This is an underrated reason for why development is so hard in a classic Main Street setting.)

Something like South Bend, Indiana’s very cool house template program might also become more widespread:

An exciting new program from the city of South Bend offers pre-approved development templates to small-scale developers at no cost. The plans, developed with the help of incremental developers and design experts, are specifically crafted for South Bend’s existing neighborhoods, where they fit the current zoning rules, lot sizes and shapes, and market conditions, and nod to the city’s historic architectural vernacular. The catalog includes templates ranging from single-family houses of varying sizes and bedroom counts to a carriage house, a duplex, and a six-unit apartment building that can fit on a typical urban lot.

When you make something easier to do, people do more of it; when you make something harder to do, people do less of it. It’s a trite observation. But if you make something easy to do that nobody wants to do anyway, it won’t make any difference.

We could set up little water pumps and dispensers at every storm drain, for example, and offer little plastic cups, and put up a sign inviting people to drink the storm water runoff. We could run TV ads announcing that it is now very easy to get your fill of storm water with our free dispensers and cups! Who is going to take up that offer? Nobody.

Now we could also put government-funded ice cream stands on every corner, and put up signs and loudly advertise free, unlimited ice cream everywhere all the time!

Lots of people will be eating a lot more ice cream.

A lot of people think building an ADU is like drinking storm water. But as the numbers show, it’s more like giving people free ice cream.

I wrote, back in September 2021 when California controversially passed its statewide upzoning laws, that it was an excellent test of this theory of small developers, or what Strong Towns calls “unleash the swarm.” Here was why I liked their SB9 bill, in particular:

In my view, California has implemented an extremely smart and prudent policy here for two reasons.

One is that by being large-scale but small-intensity, SB9 helps ensure that increases in density will be distributed and modest. The more land area the upzoning covers, the more radical and sweeping it might appear—but the less it will actually change any one place. Individual communities often, probably understandably, dislike the impression that they’re being “targeted” for upzoning. Others dislike density corridors, where you have a mass of high-rises, usually along a major highway, surrounded by single-family zones. When there are no single-family zones, the result is not going to be towers going up in back yards. Rather, it’s likely to be the opposite: a little bit, not all or nothing, in everyone’s back yard.

Which brings me to the second reason: by permitting things like duplexes and ADUs on all single-family lots, this new zoning designation empowers homeowners and small-scale developers. There may be some cases where individuals find themselves pitted against developers, who see tract houses as demolition prospects for their upzoned land. But the fact is that now virtually every homeowner in California can themselves be a developer, if they so choose. We’ll probably be surprised how many will end up availing themselves of such an opportunity. This is essentially how places were built in America before the advent of zoning and mass-scale suburban growth, of the sort that Charles Marohn of Strong Towns describes as “built to a finished state” all at once and then frozen in time. That may feel stable, but it’s very fragile.

We’re still finding out the extent of small-developer interest here, but from everything I’ve seen, large developers are not buying up single-family houses. (The separate but similar pheneonon of big real-estate investors buying up single-family houses is only really happening because of supply constraints in the first place. That’s what the investors themselves are saying.)

Allowing a homeowner to build a second home on their property allows them to do something with their equity, other than sell and leave the neighborhood, or region, or state. or it allows them to retire to the smaller unit as they age, and rent out their old house for an income.

In his piece, linked at the very top, Gray writes of ADUs, and by extension other small-scale development options:

Besides the fact that many of them go in literal backyards, the success of their legalization reveals the extent to which we’ve locked our cities in a straitjacket—and the benefits of unshackling them. As soon as we granted homeowners the right to add an extra home on their lot, they eagerly lined up to do so, making neighborhoods across California ever-so-slightly more affordable.

Nobody wants to do it, except for the all the ones who do.

Related Reading:

A Hint of America’s Lost Urban History

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 400 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!