Trains are a frequent setting for murder mysteries. Perhaps their confined nature (and, in many of those classic mysteries, their socially rarefied crowd) make them perfect settings for whodunits.

But actual murder on actual trains is, occasionally, a real-world occurrence. At least in New York City, where such things seem to happen at a disproportionate rate compared to any other highly developed city in the world.

The most recent incident involved—as these incidents sadly often do—a troubled homeless man, Jordan Neely in this case, who appears to have fallen through the cracks of a bloated but ineffectual health and welfare system. And, as these incidents also sadly often do, this one sparked thousands and thousands of words, few of which threaten to do anything about the underlying problem, or help us to understand it.

For example, William Voegeli argues in City Journal that—I exaggerate a little—the murder of Jordan Neely at the hands of a vigilante ex-Marine is a substitutionary atonement for the murder in 2022 of Michelle Go by a mentally ill homeless man. Or maybe he’s blaming Jamelle Bouie, who wrote in the New York Times denouncing the vigilante killing and warning against demonizing homeless people.

One woman said that she had drawn away from Simon [the man killed Go], fearful that he might push her. But apparently, she neither screamed nor called for the police. We can surmise that even if Simon’s demeanor struck some people on that subway platform as “off” or threatening, they responded as Bouie would have approved, with restraint and forbearance.

Bouie contends, Neely’s fellow passengers were obligated to give him the benefit of the doubt.

It is also true, however, that the people sharing that midtown subway platform with Martial Simon had no way of knowing that he had served two prison terms for robbing taxi drivers at gunpoint. Or that a drug possession case against him had been dismissed in 2019 due to his mental state. Or that he had been homeless for nearly 20 years before he killed Michelle Go. Or that he had been hospitalized at least 20 times. Or that he had told a psychiatrist in 2017 that it was “just a matter of time” before he pushed a woman onto some train tracks. Lacking such knowledge, the people on that subway platform were equally obligated to give Simon the benefit of the doubt….

These situations will sometimes feel dangerous and occasionally be dangerous, but another part of being on your own is that you’ll have to figure out for yourself which situations do and do not pose a genuine threat. To make the challenge even more stimulating, be advised that the world’s most influential newspaper is prepared to denounce you if it believes your response to a particular situation was disproportionate to its true dangers.

“There is nothing [Jordan Neely] did” on that subway car “to deserve death,” Bouie declares. But denunciation is not the only risk of assessing and choosing incorrectly. Michelle Go did nothing on that subway platform to deserve death, either.

I don’t know William Voegeli, nor did I really know who he was. This is from his own website:

For decades, conservatives have chafed at being called “heartless” and “uncaring” by liberals, without ever challenging this charge. Instead, they’ve spent their time trying to prove that they really do care. Now, political scientist William Voegeli turns the tables on this argument, making the case that “compassion” is neither the essence of personal virtue, nor the ultimate purpose of government.

At least he’s honest.

What we are seeing here, I think, is bad situations—a sclerotic institutional response to crime, homelessness, and untreated mental illness, something New Yorkers have dealt with for decades—giving rise to ideas which eventually take on a life of their own.

These ideas, in turn, make it harder to solve the problem, and come to exist independently of it, like a tree which no longer requires roots, and forgets that it ever had them. These disembodied abstract attitudes, once tied to real things, are probably one of the reasons our politics is so seemingly useless, and why problems like this feel not just thorny or tricky but fundamentally insoluble.

The sorts of ideas I’m referring to are the ones expressed and suggested in Voegeli’s essay, and other adjacent ones. That homelessness is a social services and criminal justice problem only, for example. That homelessness is a moral failing, and that to solve it is to possibly reward people for moral failure (this is not an opinion that Voegeli expresses, at least not here). That speaking thoughtfully or compassionately about the causes of homelessness is at one end of a spectrum, and that taking the violent crime a small minority of the homeless commit is on another end; that it is, in other words, impossible to do both. A belief that, despite the emphasis on law and order, crime and disorder are inherent in urban life. Unfortunately, this latter belief is apparently held by some progressives, such as San Francisco’s former police commissioner:

For such people, it is more important to make a point than to solve a problem, even when that problem becomes their own. How civic-minded.

The subtext of all of this is that mass homelessness, like mass car ownership and suburbia, are modern inventions: creatures of a 20th century revolution in American life in general, and land use in particular.

Homelessness has always existed. It has been a national issue in various forms since the late 19th century, frequently following periods of rapid urban growth or economic recession. In this way, it was mostly an economic phenomenon, and not effectively a lifestyle. The homeless, as a desperate group of people separated from normal society, go back only to the mid-to-late 20th century, following—not coincidentally—the wholesale destruction of historic cities alongside the nationwide adoption of zoning codes which prohibited the sorts of last-resort housing that historically had kept transient, marginal, and unlucky people from falling out of housing entirely and into the street.

The world of dangerous, ruined cities that Boomers grew up in had really only just arisen, and yet they mistook this nadir in American urbanism for the Platonic form of cities themselves; just as they mistook the quiet, quaint, frozen-in-time small towns they adopted, one or two hours from the city, for quiet, quaint, historic lifestyle amenities rather than the erstwhile cities they were.

These errors of understanding have been baked so deeply into our politics and discussions about all of these things that few of us really even notice them anymore. They are now trees without roots. Trying to even make people aware that they hold these inherited beliefs can sound to them like ignoring the real problem. To suggest today, especially to conservatives, after decades of subway pushers and uncomfortable encounters with homeless people, that homelessness is a housing problem sounds like a laugh line.

What they hear is, “You think a nice apartment would have stopped that lunatic from shoving a woman in front of the subway?” Or they might say, “So if I start living on the street, will the government give me a house?” Or they might link Millennials’ complaints about high housing prices to the homeless-as-a-housing-problem theory: “First all the kids want free houses, now the bums on the street want one too? Nice to want!”

The fact is that the free market once “gave” low-cost, flexible housing to many people—not all—who almost certainly would otherwise have been homeless. And the government sawed this bottom rung off the housing ladder and effectively birthed homelessness as a mass phenomenon. The evidence for this is both historical and current, in that homelessness today correlates not with levels of drug abuse or alcoholism, but with high housing prices. Yet this is almost literally unbelievable to a lot of people. (As is the fact that those quiet small towns to which many ex-urbanites fled once competed to grow bigger, to build more, to get on the map.)

And so ideas of deservingness and merit, historically ignorant and shorn of any real-world anchor, become excuses to refuse to do anything. It would be wrong to allow housing for homeless people to be built, because that might get them off the street, and they don’t deserve that.

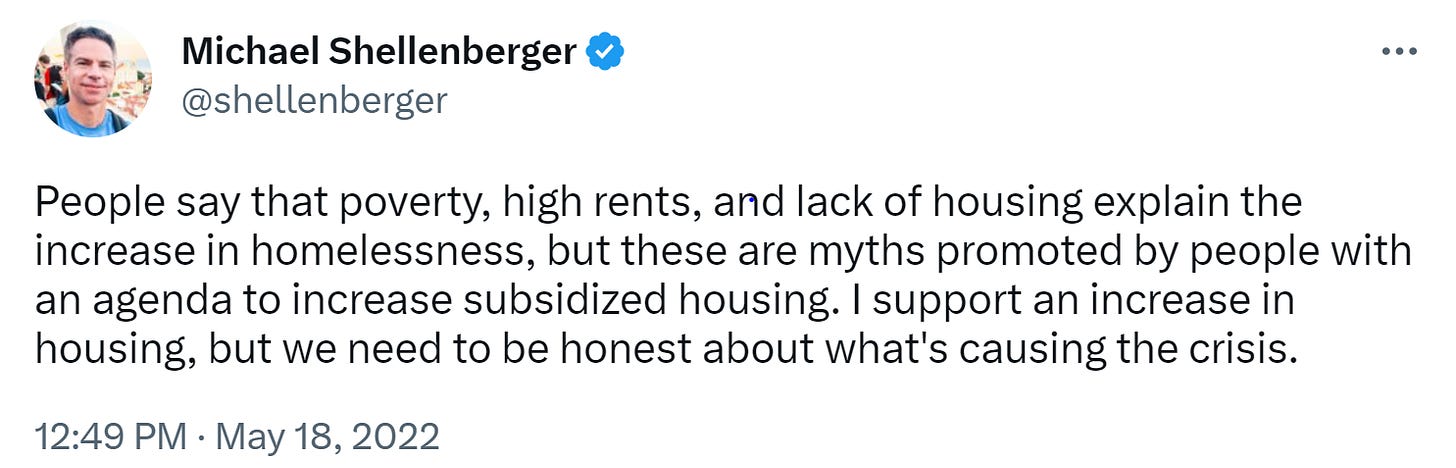

Michael Shellenberger, who went from market-friendly environmentalist to whatever he is now—he identifies himself in his Twitter bio as “pro-civilization”—has this to say:

In another tweet, he writes, “What does work? Shelter First, Housing Earned. This is known as ‘Contingency management.’ It rewards abstinence, working, and/or taking your meds.”

I’m not deeply knowledgeable on the policy wonkery here. I assume all of this depends on the sorts of homeless people you’re treating, and what, other than missing rent, led them to end up on the street. Maybe some of them need Shellenberger’s treatment.

But it seems to me that “abundant housing would reduce the number of people who end up homeless” is true no matter what is true of those who are already homeless. Yet folks like Voegeli and Shellenberger rarely say something like, “Look, housing fixes the problem in the future, but we need more to fix the problem now.” They instead make an idol of virtue. They make their perfect the enemy of the real good. And they conceive of a necessity like housing as a cookie jar, and the most desperate people in our society as toddlers to be tut-tutted about eating their vegetables.

And some, of course, do worse. When people tacitly defend vigilantism, up to and including killing people who make them uncomfortable, they are betraying a moral wickedness. But they are also betraying a deep cultural and historical amnesia, and a deeply constrained vision of what is possible.

Some of the minority of homeless people who are deeply ill may never live stably on their own, in proper housing. Some small number of people never will. No market solution or government policy will perfect us; human nature is a chronic condition. Conservatives are supposed to understand this. It doesn’t mean policy is useless or illegitimate. It just means it isn’t all-powerful. Zoning did not make Jordan Neely act strangely on the subway. Ineffective policing did not make an ex-Marine choke him to death.

But if American cities were allowed to breathe again, unconstrained by the accretion of decades of rules and regulations against doing things—bans on building boarding houses, bans on selling churros, bans, in many ways, on being fully urban and being fully human—they would be freer, finer places for everyone.

Related Reading:

Housing, Homelessness, and the Elephant in the NIMBY Room (The Bulwark)

Thinking Bigger About the Housing Crisis

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 600 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Similar pattern to the zero response on the gun issue and the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” economics, no? The more I hear politicians talk about their reasoning behind these things, the more I just keep hearing “generational trauma” in their personal stories. Not to be too broad, but in the end can a lot of this be traced back to the effects of WWII? Seems unrelated, but I’m not so sure.

Great essay. Thank you!

City Journal has a strong conservative slant from my viewing. If we knew the funders that could be made clearer.?

The comments about being afraid made me think of a purse being stolen from a car a decade ago or a murder within two blocks of my home and an area where I walk. Neither of these Lansing Michigan events make me fearful. Careful and vigilant perhaps, but life is full of randomness that we try to avoid realizing.