Thinking Bigger About the Housing Crisis

Urbanists need to make cities not just livable, but great

Today’s piece is a guest article by Luca Gattoni-Celli, the founder of YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, an official chapter of YIMBY Action. I know Luca and I belong to his group. Much of the content of this article will be familiar ground for many of you, but not for all. Aside from economic arguments for housing and urbanization, Gattoni-Celli argues that we should make cities so great that their greatness as places to work and live will speak for itself, and overwhelm the ability of critics to breezily denigrate cities and urban life.

Housing policy and urbanism are going mainstream, ostensibly because housing affordability has become a crisis personally affecting most Americans, particularly the upper-middle class who set the agenda in American society and politics. It is no longer a working-class problem or a largely non-white problem. And it is no longer a coastal crisis, but rather a crisis everywhere with a reasonably healthy job market—and even in many cities with weak economies (think places like the Rust Belt or amenity towns that cater to tourists).

This New York Times article about Spokane’s struggle to absorb population growth fueled by remote workers and people fleeing high-cost metros crystalized for me that our model in the United States for how cities grow and how we view other people is fundamentally broken.

“Am I a burden?” asked Jane Green five years ago. She felt unwelcome as a new resident of Arlington, Virginia, D.C.’s innermost suburb. Jane became a housing activist and is now president of YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, a grassroots pro-housing group I founded in August 2021. Our ultimate goal is to help build a new model for population growth: not just socially and culturally but also institutionally. Otherwise, newcomers will continue to bid up local housing prices. Addison has written insightfully about how the distorted housing market corrodes our collective ability to coexist, politically and in daily life.

I hope to nudge my fellow housing advocates and urbanists to think bigger about what it will take to make housing affordable, and to build a new, sustainable model for cities to grow. Spoilers: cities will have to be allowed to grow a lot bigger, and urban places must function better.

We will be focusing on housing unaffordability as a supply problem. If you are skeptical, I have two responses. Firstly, the housing shortage is the only plausible root cause of the affordability crisis, even granting the importance of other factors. Secondly, barriers to market rate housing weigh even more heavily on subsidized housing.

It was a veteran affordable housing developer who told me that Arlington’s site plan process costs $1 million dollars a pop. Nonprofits and charities are not exempt. And it was a staff member at a homeless shelter who explained to me and a member of my team that rising rents have increased the local population without stable housing, and that the shelter struggles to simply find unoccupied homes to place its clients in.

As Addison has masterfully argued, cities are different in degree, not kind, from towns. If a community is minimally built up, i.e., not rural, it is best understood as existing on a continuum of size and density. One of my favorite aphorisms is that God punishes us by giving us what we want. If YIMBYs got what we want, a housing boom might exacerbate problems — some perceived, others very real — in relatively dense places in America, as cities moved up that continuum. The backlash might take root in influential suburbs. And the political center might not hold.

But before getting into that, we need to discuss agglomeration.

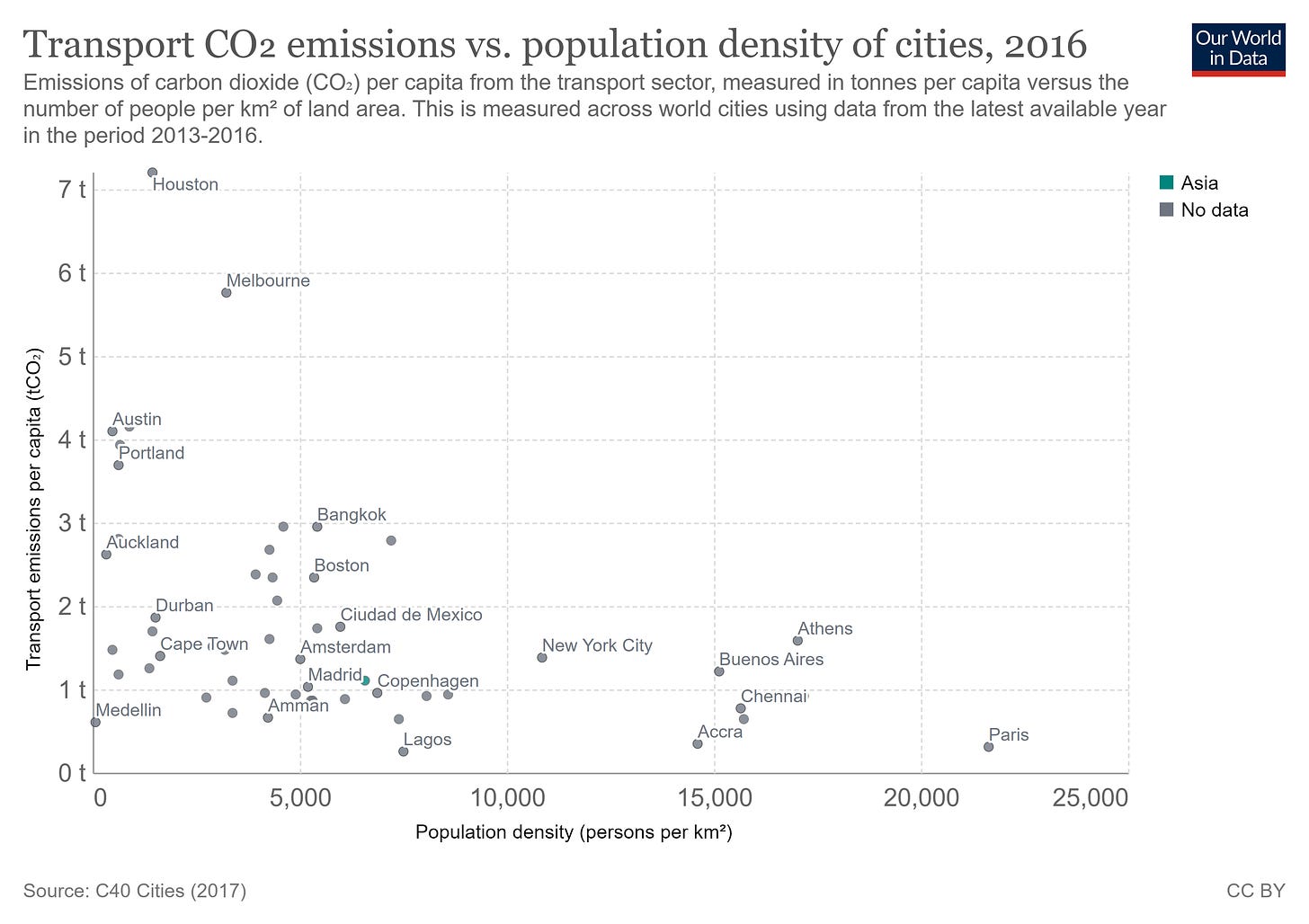

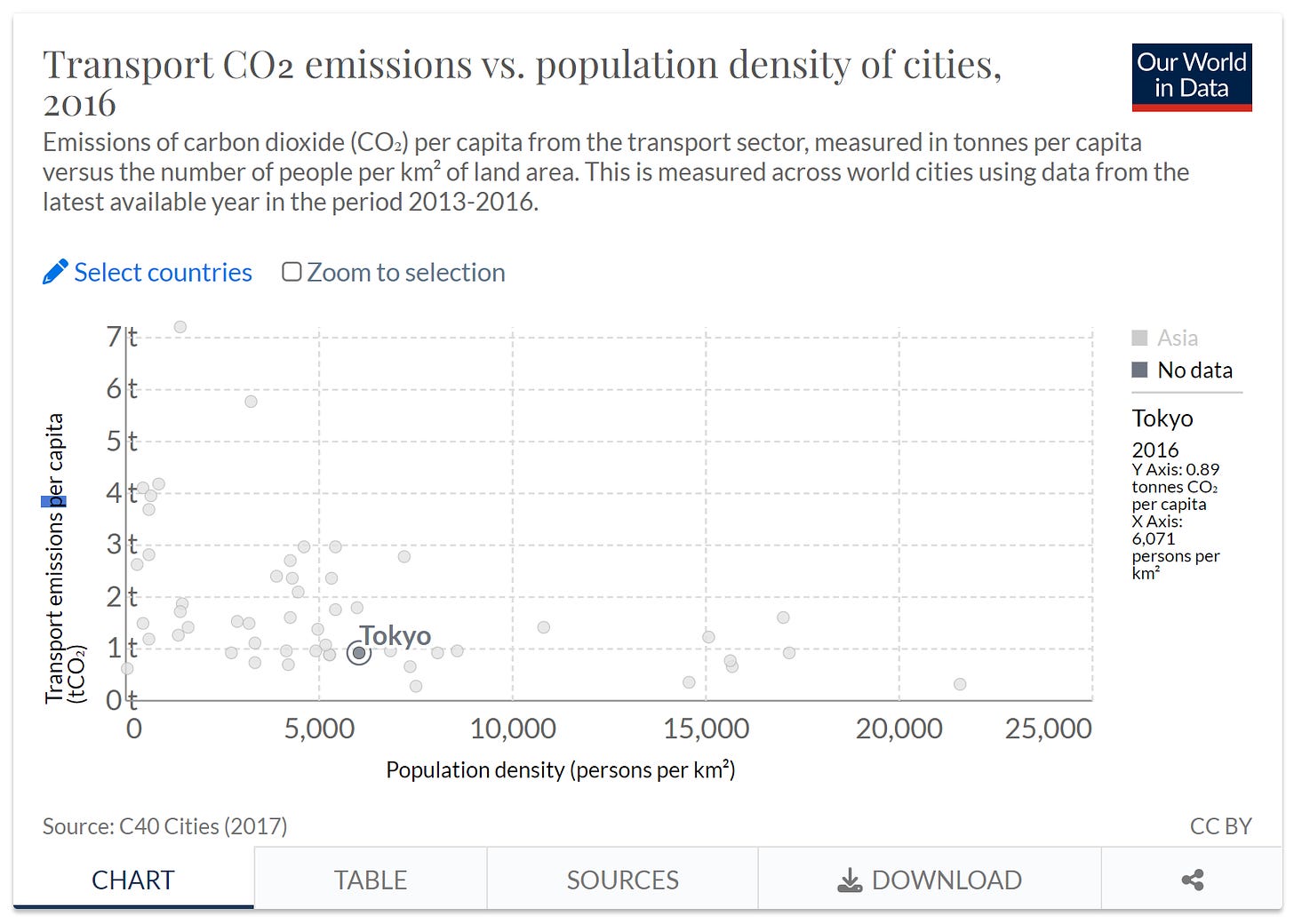

Agglomeration is the economics term for the positive, i.e. self-reinforcing, feedback loop of productivity growth and innovation from many people being in close physical proximity. Urbanists tend to think in terms of complex systems, which they should. But I would argue that population density largely dictates everything urbanists care about, from housing costs to carbon footprints to mass transit’s viability. (Chart source here.)

The U.S. is probably short many millions of homes. For example, Annie Lowrey’s recent article in The Atlantic, The U.S. Needs More Housing Than Almost Anyone Can Imagine, dug into a somewhat controversial but directionally correct paper by economists Enrico Moretti and Chang-Tai Hsieh, which estimated huge economic and migratory effects if New York, San Jose, and San Francisco had the housing permitting standards of Atlanta or Chicago.

Despite the affordability crisis’s geographic ubiquity, that massive shortage is still concentrated: in the places people most desire to live. Places with many other people, which have jobs, opportunity, big institutions, diverse amenities, and cultural vibrancy, from the immigrant-driven international cuisines Addison and I love to prestige haute cuisine, museums, and performing arts venues. Some of the D.C. region’s best food is in the suburbs, as Addison has documented, but those suburbs exist because of D.C.

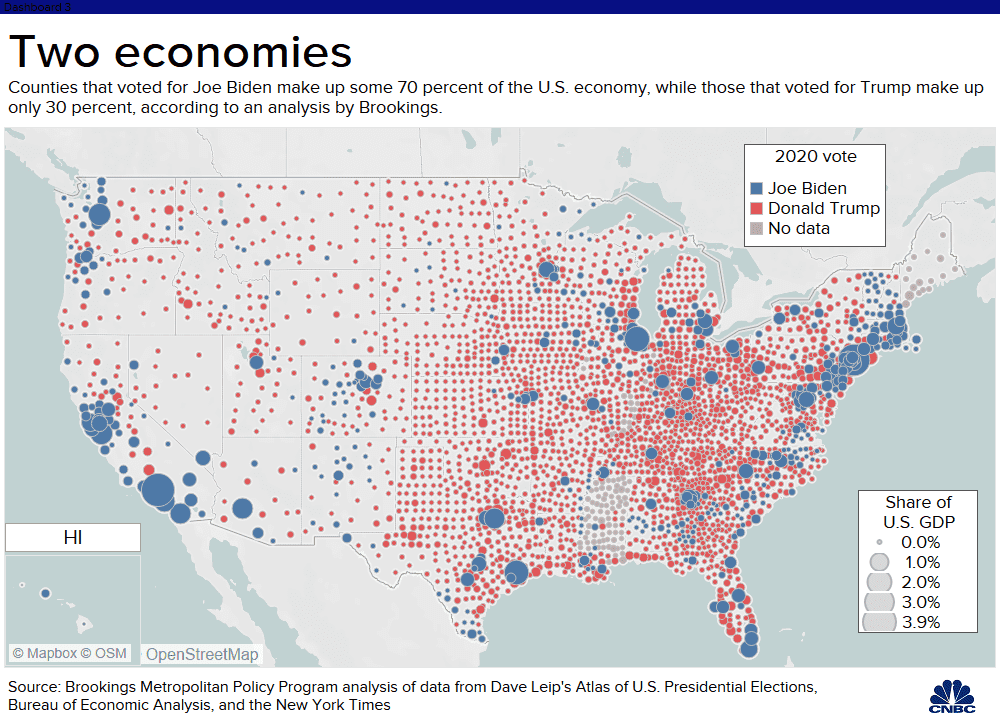

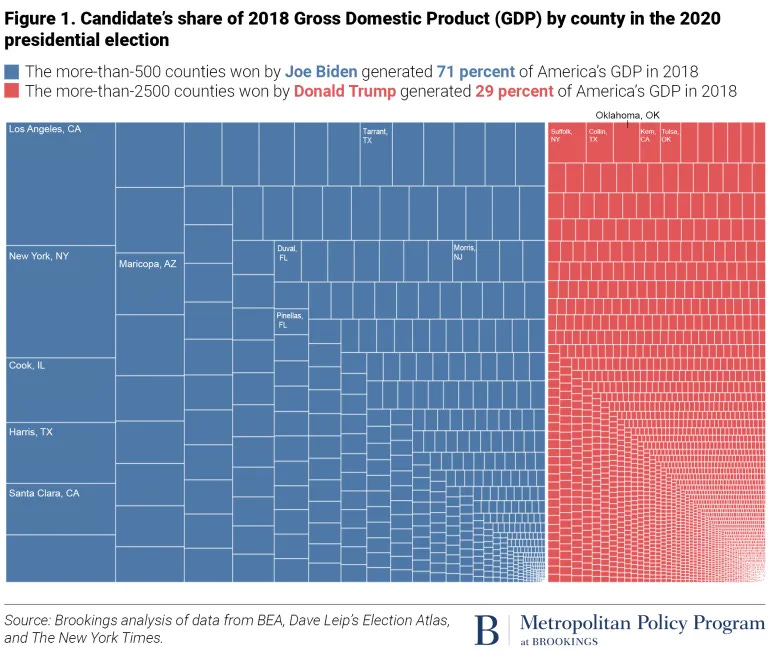

The U.S. housing shortage is most concentrated in superstar cities with the most opportunity. And cities really do have the lion’s share of opportunity. Below is a map of U.S. GDP. Blue dots are counties that voted for Biden in 2020, red dots are where Trump won. But as the map title suggests, focus on the economics, not the politics. The blue dots comprised 70 percent of U.S. GDP in 2018. And they are very obviously our urban centers. The U.S. economy is urban, by a landslide. (Biden received a comparatively modest 51.3 percent of the popular vote.)

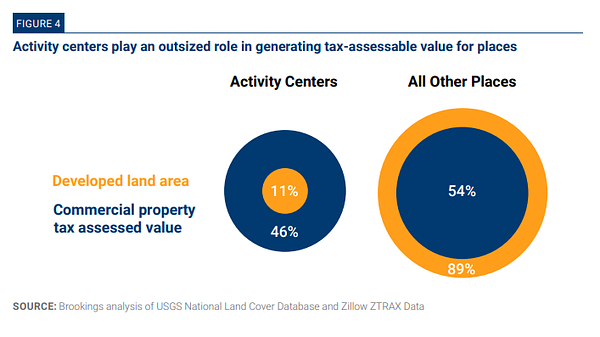

What about suburbs? The original Brookings Metro graphic that went semi-viral after the 2020 election makes pretty clear that economically, suburbs are hangers-on. Cities are the undeniable engines of the U.S. economy.

Thus, we must allow cities to grow. Recall that agglomeration is a positive feedback loop. Opportunity and jobs attract new residents, who together create new opportunity and jobs, and so on. New enterprises form, the rate of scientific discovery will hopefully accelerate, we can expect to see new cultural expressions and of course lots of good food. The economic boom from simply letting cities grow is incredible to contemplate.

Letting the supply of homes grow to meet the quantity demanded will also make them less expensive, to a point that the housing market functions like most others, instead of the cruel tournament of scarcity we have now. The upshot is that abundant affordable housing in a region rich with opportunity will attract many new residents to that region. Allowing cities to grow, as we must to enable people live near employment and opportunity, will cause cities to grow much larger than they currently are.

How much larger? How can we get an idea of the upper limit on a city’s size? Well, Japan is famous among urbanists for its permissive national zoning code. Just get a load of this. It is lightyears ahead of our zoning:

And Tokyo is the world’s most populous metropolitan area, with almost 40,000,000 residents. Its population is on par with the entirety of Canada, earth’s 37th most populous country. New York clocks in at 11th among metros. By the same 2018 UN estimates, New York City has about half the population of Tokyo. And Tokyo rents are roughly a third, or half as expensive as in major American cities. Remember that CO2 versus density chart? Tokyo’s per capita transport emissions are very low, despite fairly modest population density by global standards.

Now, to be completely fair, I am just a guy on the internet, right? But it sure is interesting that the largest urban center in Japan—the country with the most permissive land use regime, and the third-largest economy—is also the largest metropolis on earth. And it sure does suggest that if you let a city grow, it will grow a lot.

You know the factoid that a goldfish will grow larger depending on the size of its bowl or tank? In the wild, goldfish are a formidable invasive species. According to various sources they can grow anywhere from 12 to 24 inches long. One article reports multiple 18-inch four pounders. Right now our cities are like goldfish trapped in small bowls. Again, just imagine letting a city grow. D.C. has a height limit. Even Manhattan restricts residential density.

This points to the next-order consideration: we as housing advocates, and really as urbanists more broadly, should help better manage the basic institutions and negative externalities associated with residential density. The problems that jump out to us largely stem from cars. And they are real and serious problems: traffic congestion, air pollution, noise pollution, inefficient uses of land, danger for everyone involved to the tune of 40,000 Americans killed annually. Cars ruin cities, no argument from me.

But I challenge us, as urbanists, to be honest with ourselves about other urban institutional failures: schools, economic opportunity for poor residents, crime that disproportionately victimizes those same residents — stuff our antagonists love to lord over us, but that we as urbanists must engage with if we want cities to thrive. Thinking bigger includes envisioning a WMATA (the D.C. region’s public transit authority) where level of service and frequency are the north star, not chronic problems we make excuses for. Brake pad material (I hope?) clouds the air of some Metro stations. Is everyone supposed to just wear an N95 and act like nothing is wrong?

Riding the Metro should not be a political act. The trains should just work. When I came to D.C. in 2012, I thought the Metro was incredible. Some of that was having almost no prior exposure to public transit, but it really was awesome, so much better than it was even right before the pandemic. I abandoned a Metro commute that saved me a lot of money — even with my hourly wage as a proxy for my time value of money (yes I actually calculated that)—because it was so unreliable.

And now lines shut down for months at a time, hurting the people who rely on the Metro. Routine maintenance, following safety procedures — some of this stuff is basic. Even with WMATA’s spotty safety record, Metro is way safer than driving, but passengers need to have basic trust in the system. The Metro must become convenient, full stop. Randy Clarke, WMATA’s new GM and CEO, is saying the right things; hopefully he can really turn it around.

We urbanists understand how important institutions like the Metro and D.C. public schools are, but they still have a lot of problems. (Admittedly DCPS’s problems are not unique to it, even in the region as a whole, which opens up a whole other can of worms about institutional problems with the American education system.) Cities are a work in progress, granting that much of the work is outside of urbanists’ remit. I am not advocating that we wade into policy areas we do not understand. But we should find ways to support credible efforts to fix urban institutions.

I discovered urbanism less than two years ago, at just the right time. It felt like catching a wave. I happily watched as my passion gained acceptance. Of course there is a housing shortage. Of course America’s addiction to cars is toxic, and electrification is not a silver bullet. The New York Times and The Atlantic now have regular deep-dive stories about housing affordability. Fast Company is spreading the good news. CNBC’s YouTube channel is getting millions of views for videos about car-free cities and the housing shortage.

Most urbanists have been in this struggle for years, so by all means, enjoy the moment. But we must meet it with serious, tangible plans for making cities work for people who, as we see so often, do not realize they already live in a city, and do not want it to grow. Otherwise we will continue fighting the same battles, even if housing becomes affordable.

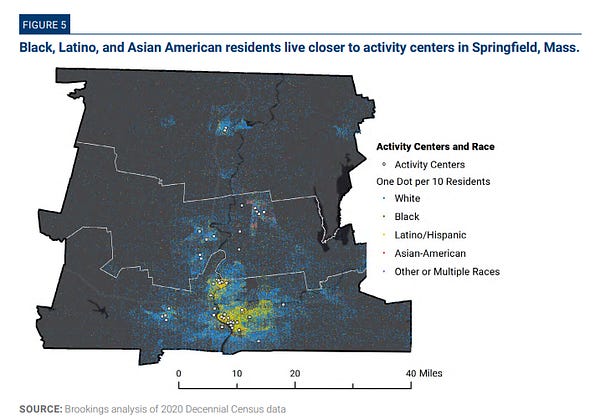

The best way to make the case for the city in American life is to make cities’ core institutions better. The city should make the case for itself. It should be an undeniable land of opportunity, a beacon of progress. Urbanists have very little control over the narrative about urban places in America, but we can help make them great. On the topic of hyper-local inequality of opportunity, I was struck by this recent analysis from a local YIMBY and incredibly talented researcher:

We all have a responsibility to square that circle. We cannot shrug off all accusations of urban dysfunction—granting that many are baseless political hackery—as cherry picking or bad faith. Tokyo is a shining example of a functional city. It shows that a better world is possible. The U.S. is still likely the only country capable of putting a human on the moon (sorry, EU), but lots of American cities could emulate the good and great things about Tokyo. We should at least try!

As we do try to make cities function better, there is still a moral imperative to love thy neighbor—however distorted the housing market, however institutionally incapable it is of accommodating newcomers. The Brookings Metro visuals throw into sharp relief the folly of resenting a basic fact of human existence: physical proximity to other people. You can live alone in a cabin in the woods, sure, but very few people would be capable of subsisting and surviving entirely on their own.

We have always relied on each other for survival. We still do. A driver saying “I hate traffic” implicitly does not view their car on the road as traffic (assuming they do not hate themselves). But we do engage in a kind of self-hatred when we are hostile to new neighbors.

The Christian themes here are impossible for me, as a believer, to miss. Not just of loving thy neighbor, but the centrality of cities in human experience. Early Christians gravitated toward cities. To be a fisher of men, you must seek people out. Jesus ultimately took His ministry to Jerusalem. Early Christians proliferated in, were martyred in, and ultimately triumphed in Rome with the conversion of Constantine—whose other great legacy was a new capital city.

Especially in the depths of a dire housing shortage and affordability crisis, figuring out how to welcome new neighbors is a necessity. We must learn to coexist. We cannot continue to view other people as a burden. Fortunately, YIMBYs and urbanists have a positive vision for the future, and are doing the work to try and make it real. So keep doing the work. Let yourself dream big. We need to dream a lot bigger.

Social card image credit Flickr/Derrick Brutel, CC BY-SA 2.0

Luca Gattoni-Celli is the founder of YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, an official chapter of YIMBY Action, a national advocacy network. He currently works as a business researcher. You can read more of his writing about urbanism at his Medium blog and follow him on Twitter at @TheGattoniCelli. Luca lives in Alexandria, Virginia with his wonderful wife and two children. They enjoy hiking, e-biking, and the stellar food in NoVA from around the world. Email Luca at LGCSDG@gmail.com. He would love to hear from you.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 400 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!