The other week I gave a talk at a public library in Woodbridge, Virginia, a mostly suburban community about 40 minutes from Washington, D.C. I outlined what I would be talking about here, and I stuck to this pretty closely.

This is really the core of my argument:

“People cause traffic” is almost like saying “Cooking causes the fire alarm to go off.” Only if you cook badly! People cause traffic only if you force them to rely on cars. And the further we put new construction and new housing away from the urban core, the more we separate and isolate everything, the more people will end up causing traffic.

And in my talk I quoted another article:

It’s a self-reinforcing problem: in order to dilute traffic, we dilute development, which intensifies traffic, which intensifies the desire to dilute development.

In other words, the common objection that new housing causes more traffic is only true if your land use requires people to drive everywhere. Which, in most of America, it does. But true towns and cities and good mixed-use development (plus transit) are like magic: they decouple people from traffic. That feels impossible if you live somewhere that forces every single errand or trip to be a car ride.

Read the whole thing.

What I’m writing about here is the Q&A discussion we had at the end. It was a small crowd, which meant we had some real conversation.

I’ll start with a woman who lived out in the Fredericksburg area, in Stafford County, which is growing rapidly in a dense but almost completely car-dependent pattern: apartments, townhouses, detached houses very close together but not near anything. There’s no incrementalism here: these places go from country/semi-rural to dense suburbia overnight. Fredericksburg is about a one-hour drive from Washington, D.C., no traffic. And there’s never no traffic.

“They’re building these big apartment buildings in the middle of nowhere on country roads,” she said—more than 20 recent large housing developments, by her count. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Now, given the incentives and constraints that builders and residents face, it does make a kind of sense. But it certainly doesn’t make sense in theory. Nobody thinks it’s ideal. It isn’t designed. It makes sense in the way that the platypus makes sense.

That feeling, that question—why are they putting these big apartment buildings here in the middle of nowhere?—that’s the little crack where the conspiracy theorists stick the crowbar and start prying. That’s the origin of ideas like “Barack Obama instructed HUD to identify nice suburbs to ruin with affordable housing for undeserving poor people.”

I think you have to understand a lot of older folks in these semi-rural communities look at these 5-over-1 apartment buildings sprouting up the same way we’d look at an alien ship landing in a cornfield. It’s completely foreign to their understanding of how people want to live. They are often unaware that this is a symptom of a housing crunch in other places closer to the city. It’s like the shrapnel thrown from an explosion. They don’t see the explosion, and they wonder if they’re being targeted with the shrapnel. (That’s just an analogy; building housing isn’t like bombing a community!)

The point is that I basically think NIMBYism in these outer communities is somewhere between defensible and actually correct. I don’t think these are good places to warehouse people, away from everything because the places with everything want everything but more people. Those places are the expensive, underbuilt inner suburbs in Arlington and Alexandria and the analogous communities in Maryland. Places that were built in a very different era and whose land use no longer matches what the region has grown into.

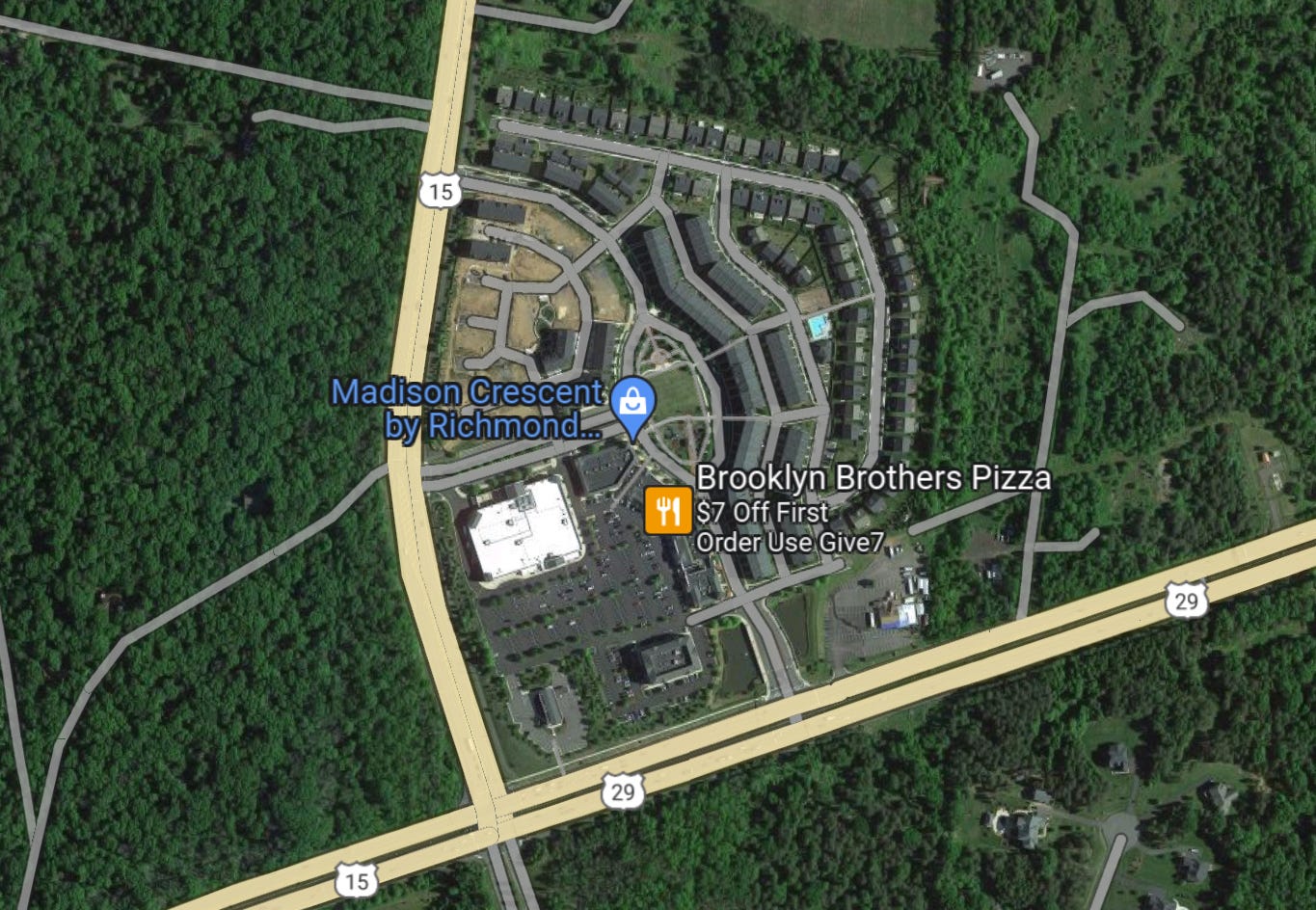

In my discussion of how denser, mixed-use development could alleviate traffic, I made this point: that it’s a good thing we’re trying to reform and improve land use to some extent, but maybe it shouldn’t be going in remote places. This was my example: a mixed-use development in Gainesville. That’s Prince William County, the same county as Woodbridge and two counties away from D.C. About 40 minutes, no traffic.

Look at the development versus its surroundings:

Someone observed that even if you could walk to the store and drive less, the people living in these new developments are almost all working in or near the city, so many of them are still commuting and contributing to rush hour crunches. (There’s no rail in Gainesville. There is in Fredericksburg: a station on the VRE commuter train. But the times are relatively infrequent and inconvenient for a lot of commuters, and driving is the common way to commute.)

This housing you see sprouting up in outer communities is not mostly for people who live in those communities, per se. You have places with more jobs than housing—which means there are places with more housing than jobs. These bedroom communities exist in the same space as pre-existing communities, but they are not of them. Frequently people do not particularly want to be there. It’s a kludge. It’s the best combination of prices and values they could find. It doesn’t make any sense.

Normally, when looking for a home in a metro area, you would choose between more space and a long commute, or less space and a short commute. Do I want to live in a big house with a little land and drive an hour or two a day? Or do I want to fit my family into a townhouse or condominium and have a short commute and access to a lot more stuff? That is the choice that our regional land use should present to people.

But this housing in these far-flung places is effectively inner housing which has been transposed into outer communities. It is a result of zoning—not the zoning that permitted it in Fredericksburg, but the zoning that did not permit it in Arlington.

We’ve inverted the natural density curve of metro areas. You have people moving all the way out to Fredericksburg to live in a townhouse or an apartment and then commute in gridlocked traffic back to the immediate D.C. area. And you have most of the land area in Arlington looking like it did a century ago. These inner communities are holding onto the jobs while exporting urban housing to the countryside.

One woman said that her daughter and five other girls rented a single-family house together in Arlington. Legally, she said, that’s defined as a brothel. This is a market failure. It’s the market telling us something is wrong. Those six young women living in a suburban McMansion a few miles from downtown Washington D.C.—that should be reasonably affordable apartment units. But those do not exist unless you leave Arlington for Fredericksburg. The people who insist on a 2023 economy but a 1930 zoning code are imposing an economic and social tax on the entire region and its current and future people.

Look, I’m not bashing Arlington. It’s just the most pertinent example, on the Virginia side, of this phenomenon. They are building some housing, and they just passed a big “missing middle” housing reform, which allows some low-intensity multifamily in single-family zones. I think that’s a reasonable compromise. My point is broader: if we sat down and planned the whole region, we would not build what we currently have now.

Another person asked about dedicated bus lanes. There’s a proposed project on Route 1 in suburban Alexandria—the Richmond Highway BRT (bus rapid transit), which acts like a tram or subway line with less required infrastructure. And further north there’s already such a bus line, implemented in 2014. It’s popular now and has relatively high ridership. But in the beginning it shut down a prime highway lane despite garnering relatively low ridership. And the result was that this person moved further south, to a much more car-dependent area.

So, he asked me, playing a little bit of devil’s advocate, should we screw tens of thousands of motorists for a few thousand bus riders, with the idea that the bus will eventually fill up and help alleviate the longer-term traffic problem?

I don’t think in terms of screwing people; I think in terms of trade-offs. I think of a tough decision my dad’s college had to make when he was there: shut down the football team. It wasn’t winning or making the school money, they determined it was a liability, and they axed it. (He didn’t play football, thankfully.) For the students who played, or who went there to play, it seems horribly unfair. But it’s also unfair to privilege what is only at any given moment a handful of students over the long-term health of the college.

I guess I think of reserving a lane of a main highway for buses—or upzoning single-family neighborhoods in inner suburbs—as “shutting down the football team.” It’s not “screwing” people; and if it is, it’s “screwing” a lot fewer people than get “screwed” when narrow interests hold the long-term health of the region hostage.

And besides, we get used to change. The transition is the hard part; the final state on the other side of the transition is usually fine. That uncomfortable but brief transition period is all that prevents us from doing the better long-term thing.

I ended the same way I ended my piece here outlining the talk:

We need to build more places, and fewer spread-out, disconnected, sprawling bits and pieces of places, all five or 10 minutes of driving apart. We need to preserve the contrast between urban and rural, instead of eating up the countryside with low-density suburbs. And when the jobs and people come, we should be pleased. We should take people wanting to live in our communities not as an insult or an imposition, but as a compliment.

Because what the hell is a city or a community for if it isn’t a place for people to live?

Related Reading:

Taking Off the Car Blinders, Opening Your World

No Housing Please, We’re a Community

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 700 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!