I’ll be giving a talk at a library in Woodbridge, Virginia in June, on the (broad) subject of development and traffic. Which means land use and transportation. I’m going to lay out/think through a rough preview/dry run of my talk here. Tell me what you think!

Woodbridge is not adjoined to Washington, D.C.: it belongs to Prince William County, which borders Fairfax County, which borders Arlington County, which borders D.C. Parts of Prince William County have been heavily settled since the postwar era, chiefly Manassas and Woodbridge. And Manassas has an “old town” which goes back much earlier, as do some other settlements. But much of Prince William is still rural, and much of the growth and population there now is recent and takes a typical suburban-sprawl form.

Like most of this development in and around Woodbridge:

This is also in Prince William County: a mixed-use zoning district in which townhouses are sprouting up—in the middle of a rural-exurban stretch of U.S. Highway:

Like many of the region’s outer counties, creeping, radiating sprawl has pulled Prince William County into the metro area, bringing more people, more traffic, and cultural changes that many old-timers are uncomfortable with. In Prince William, this exurban sprawl is even controversially reaching the “Rural Crescent,” a semi-protected rural-agricultural area of the county, almost 50 miles from downtown D.C. “Don’t bring the city with you,” some people say; “Leave us alone, just let us live in peace.” (Someone said that to me when I praised his small town.)

But one of the most common objections to building anything, especially housing, is traffic. “Our roads can’t handle more traffic,” “We already have too many traffic jams,” etc. But this sort of assumes cars and people go together—that they’re almost the same thing.

“People cause traffic” is almost like saying “Cooking causes the fire alarm to go off.” Only if you cook badly! People cause traffic only if you force them to rely on cars. And the further we put new construction and new housing away from the urban core, the more we separate and isolate everything, the more people will end up causing traffic.

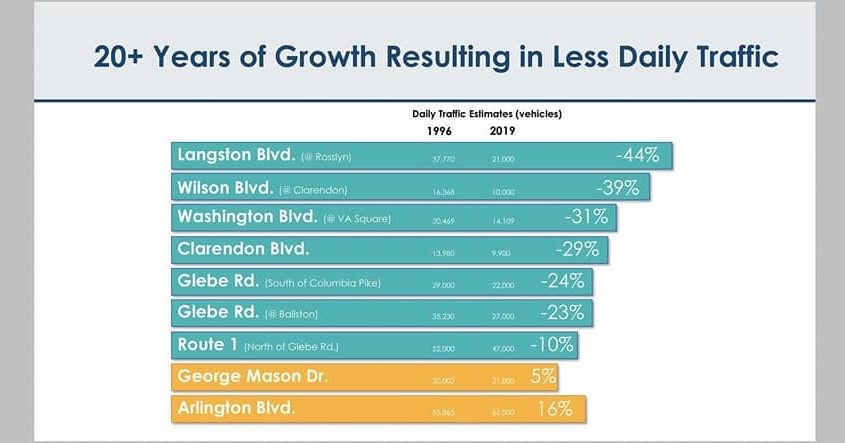

There’s a really interesting graph from a traffic study in Arlington, which, yes, has a lot of traffic. But what it shows is fascinating: despite growing tremendously in the last two decades, Arlington has not seen more traffic along with those new people. Most major thoroughfares have seen a considerable decrease in traffic!

Arlington did this because it has density along a transit corridor—the Metro, and lots of bus routes—and many walkable and bikeable (or scooter-able) neighborhoods. Many people still own cars. But every single errand doesn’t generate a car trip. Density doesn’t cause traffic; distance does.

I wrote about this bouncing off a story about the proposed redevelopment of an aging strip plaza in Virginia Beach. All of the typical objections were raised, especially traffic. “It’s a self-reinforcing problem,” I wrote. “In order to dilute traffic, we dilute development, which intensifies traffic, which intensifies the desire to dilute development.”

It doesn’t work—huge areas of low-density, utterly car-dependent development generate traffic even as they spread people out, add time and friction and expense to every trip, and dilute the critical mass of people that make places complex, interesting, enterprising, and productive.

So the way to reduce traffic and the sense “overcrowding” and “overdevelopment” is, counterintuitively, to build more densely. But what if folks in the outer counties just don’t want growth—not suburban sprawl, not “city-style” dense development either?

I think the case can be made that urban growth should not be this far from the urban core—that the contrast between country and city should be preserved. The attitude of people here should be more nuanced than “stop development” or “leave us alone.” The fact is, folks in these outer, exurban, formerly or partially rural counties—parts of Prince William and Loudoun, Fauquier, Clarke, Culpeper—need to be housing advocates for housing in Arlington, Alexandria, and in Maryland, Silver Spring and Takoma Park.

You can go to your own development hearing and NIMBY the proposals in your own county. But you should also go to the hearings in Arlington and Alexandria and Fairfax. When the NIMBYs in those localities talk about, for example, losing tree cover, what they mean is, “One tree in Arlington is worth 50 trees in Prince William.” When they talk about “neighborhood character,” what they’re saying is that a community a stone’s throw from downtown D.C. has more of a right to preserve a land-use pattern from the 1930s than small town and rural communities 50 miles from the city have to preserve theirs. The people and the jobs are not going away. Somebody has to hold the bag.

But of course, while I think inner communities close to the city should—and, in the absence of restrictive zoning, naturally would—densify and “hold the bag,” I don’t think urban growth is bad. It isn’t “getting left holding the bag.” Communities in America used to compete to build and grow. More than a century ago, a newspaper article about a small village in western Virginia described the effort of a few wealthy town families to upgrade the train station. And it contained this line: “This is the spirit which builds cities.”

Today—largely because of the car and traffic, not because of the people themselves—our attitude has flipped. There’s a line we have about people who move to a distant suburb and then turn into NIMBYs: “Everyone wants to be the last person to move in.” That isn’t possible. That is, in a way, the negation of a human settlement; the negation of a place.

We need to build more places, and fewer spread-out, disconnected, sprawling bits and pieces of places, all five or 10 minutes of driving apart. We need to preserve the contrast between urban and rural, instead of eating up the countryside with low-density suburbs. And when the jobs and people come, we should be pleased. We should take people wanting to live in our communities not as an insult or an imposition, but as a compliment.

Thank you.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 600 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Which library?!

I don’t think you are taking into account the changes in the working environment that is resulting in migration away from big cities. Hasn’t it led to more people moving to the smaller urban locations you like to describe?