The Neighborhood Supermarket Never Disappeared

The less visible perseverance of a once-universal retail form

I was in Discourse Magazine last week with a piece on neighborhood supermarkets: small but modern supermarkets, 8,000-12,000 square feet, often in town or city locations. These were common in small towns and city neighborhoods up until the 1970s, roughly—some were still opening in the 1960s. Basically, at one time, they were simply supermarkets. But the combination of cheap land and a desire for less cramped locations, and larger parking lots and physical stores, led a lot of these stores to close or migrate from urban settings to suburban, car-oriented ones.

Here was one of the neighborhood supermarkets in my hometown of Flemington, New Jersey. Today, the mainstream American grocery chains have pretty much abandoned this retail format. My town actually would like a supermarket on Main Street, possibly in the very space that was once the old supermarket. The problem is, very few chains actually operate at that scale, and so this local land-use/retail desire no longer lines up with the way the industry does business. This a problem both for small towns and neighborhoods, and for actual or potential mixed-use developments in the suburbs:

This combined land use-retail evolution has been going on so long that there is now a key retail component missing in the American built landscape. Mixed-use developments are being constructed everywhere, with homes (often a mix of detached houses and townhomes or condos) in walkable proximity to retail and services. There are several of these developments within half an hour’s drive of my home in Fairfax County, Virginia. But the problem is that there are not enough large suburban supermarkets to anchor every desired mixed-use development. Put another way, the retail trend of supersizing grocery stores has made it very difficult to ensure that every housing development can have a grocery store in close proximity.

The evidence of this is right there on the ground: In the next county over, two mixed-use developments anchored by supermarkets lost their supermarkets! The supermarkets simply needed a much larger customer base than the immediate surroundings could offer. This is a fascinating problem: A development largely outside of land use, per se, now affects our ability to build amenity-rich communities.

This is an important point: recreating old-fashioned urbanism is not possible through land use alone. It also requires commerce scaled to Main Street—not boutiques, but real, boring, everyday retail. This is one of the more subtle things that the suburban revolution has made more difficult.

But.

It is true that supermarket chains have mostly moved away from this small urban format to a big-box suburban format. It’s also true that the German imports, Aldi and Lidl, have revived something like the small-format supermarket, though they are generally in suburban locations as well.

But that isn’t the whole story. Awhile back, I saw a neat post at the Northern Virginia YIMBY group’s Facebook page, highlighting a small-format Latino grocery store in Arlington called Megamart Express (Megamart is a supermarket chain whose stores are mostly larger). Here it is:

This is very small—under 6,000 square feet. Here’s the Facebook post about it:

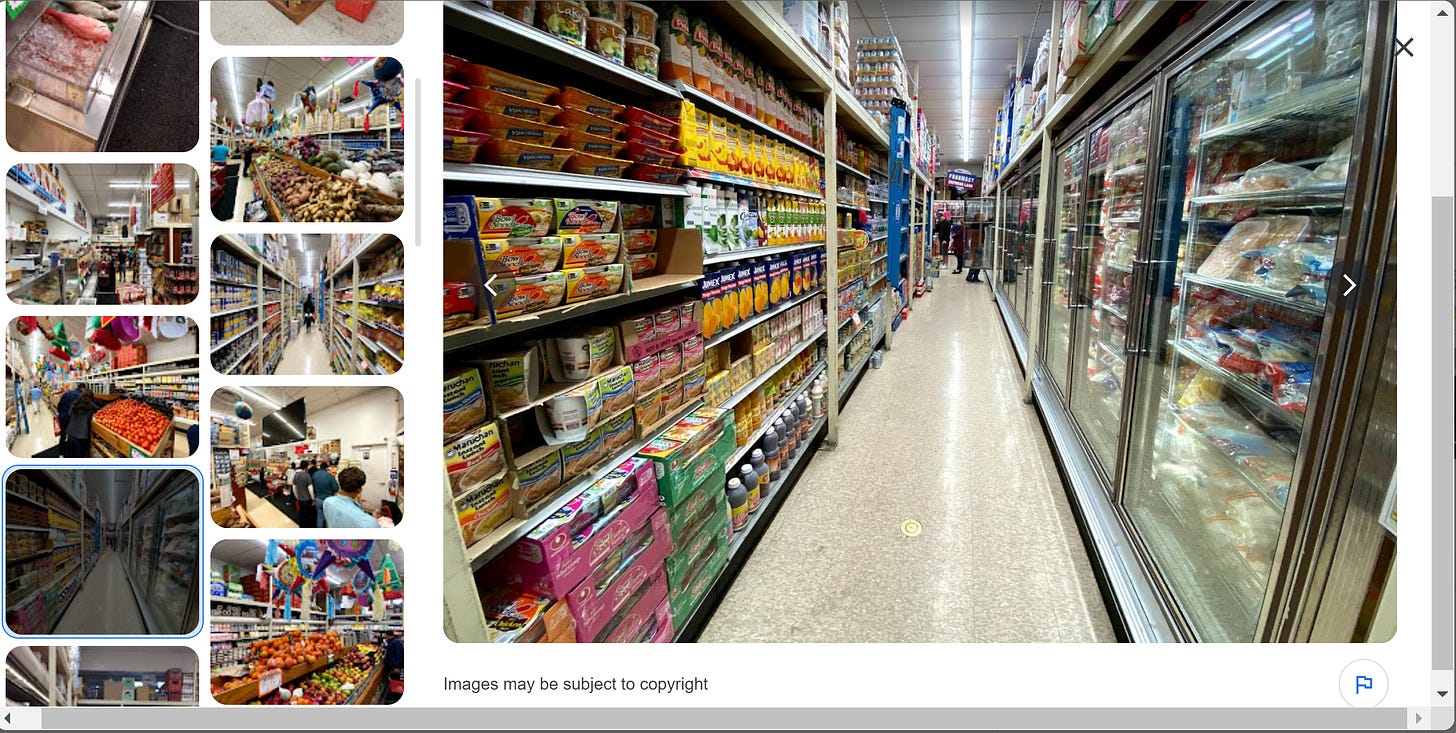

He’s not kidding about the aisles: here’s a screenshot of the Google photos for this store:

That’s a really interesting contrast to these aisles in a late 1990s/early 2000s typical big-box supermarket where I grew up, outside Flemington. Look at this:

This is subtle but very deep. What it means is that, say, a doubling of the sales floor doesn’t entail a doubling of the inventory. Small stores pack tightly; big stores luxuriate in all that space. More space has diminishing returns.

This is about scale, which is a key element of urbanism. As with cars, as with houses, as with streets, we see an increase in scale and a decrease in the efficiency of the use of space. In a lot of ways, that’s the underlying sociological and economic truth that suburban land use represents.

I once saw a fascinating thread comparing a Walmart to a suburb, with the shopping carts and wide aisles as cars and “stroads,” and a Trader Joe’s as a small town, with the narrower, densely packed aisles as streets and the baskets and smaller carts as bikes or small cars. I think about that a lot—how our perception of space and our expectations of room/privacy/crowding have changed over the decades.

There are any number of small immigrant-owned and patronized food stores—some like this, with a complete set of modern supermarket departments, others lacking fresh meat or fish but having frozen food, some having packaged groceries only with maybe a small freezer and a hot bar of prepared food. And also many single-category stores:

There are also lots and lots of small butcher shops, bakeries and food stores (without fresh produce or meat)—even older retail forms, in American terms, than modern supermarkets in a small format. I’m not talking about the handful of high-end boutique shops either. Rather, in the suburbs of major metro areas today, grocery retailing is still done in a format which predates not only the big-box supermarket, but the supermarket itself.

In the piece, I talk about how a lot of white Americans basically don’t see any of this, or think it’s kind of weird or “foreign,” because nowadays most grocery retailing in this format does seem to be “ethnic” and catered toward immigrant communities. But here’s the key:

Today, many immigrants are likely to settle in older suburbs rather than in big cities. And as they once did in cities—one of my great-grandfathers started a grocery store in America—and may have done in their own home countries, they start small businesses. It is true that immigrants tend to be more entrepreneurial than native-born Americans. But it is not true that small stores serving a local community, rather than a trade area of three or five or 10 miles, are somehow an immigrant phenomenon. All that these immigrant communities are really doing in America is what everyone did up until roughly half a century ago. We are seeing immigrants retaining something that was once universal.

One reason we don’t “see” them is because not every metro area has the diversity or the density to support these stores. In their absence, food shopping defaults to big-box chains for the most part. Another reason is simply that the foods they sell are not your mainstream “American” groceries, ingredients, and household supplies. Yet another reason is that these stores often have minimal reviews or photos online—I assume their customers aren’t the very-online detailed reviewing type—and so it’s hard to actually figure out exactly what’s for sale, or how good the store is.

In that vein, a little more on the Megamart. One Yelp review says:

I started taking photos and a manager came over to me and told me to stop. I tried explaining Yelp, he never heard of it but I assured him that I was not a competitor. He asked me what I needed to buy, and I answered candles and he escorted me to that aisle and watched me pay for them.

Sure enough, there are only a handful of Yelp reviews and photos. Nowadays an online-review presence is an important way of knowing a place exists. The fact that these stores are patronized by people who mostly don’t use Yelp—working-class Latinos, probably, in this case—makes them less visible to middle- and upper-middle-class people. (There are a lot more Google reviews and photos, which calls to mind a piece I wrote about how you can predict a community’s affluence based on the ratio of Yelp to Google reviews for its businesses. I’d like to revisit this idea.)

But the point is that because these stores exist, even in the suburbs, they can exist. Suburbia doesn’t truly force commerce at a larger scale, even though it generally has done so. It is a choice by the supermarket chains to abandon smaller stores for much larger ones with larger trade areas and greater distances between them.

And they could, if they wanted, make the choice to reintroduce the sort of stores they once built everywhere, sized properly for housing developments or Main Streets, and capable of generating a profit off a smaller and more local customer base. And we could really use those.

Related Reading:

Secondhand Supermarkets, Part II

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

This is a good post identifying a deficiency that can't, as noted, be addressed solely by changing the zoning scheme. I suggest sharing European models where large market chains have small outposts, like sub-brands. There are the large supermarkets, but the chain may also have the "express" local version catering to the neighborhood, including mostly pedestrian traffic. Migro v Migrolino in Switzerland, for example. Or, Waitrose and its smaller incarnation Little Waitrose in the UK.

I believe one of the reasons the "ethnic" small format stores can exist is their suppliers don't force them to "get big or get out" (to channel Earl Butz). Big ag and all of their food manufacturers don't want to deal with small players so they force all kinds of requirements on retailers that incentivizes large scale. My wife has worked in the food business her entire career and has shared stories with me of such strong arm tactics when she was in the retail end of the chain.