So my wife and I visited Seattle a couple of weekends ago. It’s one of those cities I’d never had any particular interest in visiting, but I was sure it was one of America’s great cities, and I had the impression that it was quaint, walkable, and historic. I guess maybe it’s one of those things.

Like so many old cities, a freeway runs right through what must have been some of the loveliest and most classically urban blocks, or at least that’s how we’d see them today if they’d survived. The touristy parts of the city, as far as I can tell, are limited to a couple of areas around the market and the Space Needle, separated by the emptied-out, office-heavy downtown. The nightlife and culture is supposed to be in “the neighborhoods,” and while that might be the case, Seattle lacks the sort of unbroken, continuous urban fabric that makes me love a place like Montreal or Philadelphia. (Or Cincinnati, which I just visited for the Strong Towns/Congress for the New Urbanism conferences, and which I’ll be writing about later.)

I was a little bit underwhelmed, and more so because I wasn’t sure why Seattle gets talked about so much.

The restaurant scene is sort of like D.C., but worse. Lots of places that may or may not be good restaurants, but which all have a gimmick. There’s the Southern-style biscuit joint Biscuit Bitch, where they say “bitch” and “bitches” a lot, including to you when you pick up your order. I’m sure it’s the best Southern-style biscuit joint at Pike Place Market.

Or The Pink Door, which has no sign or obvious entrance aside from a pink door in a wall, and which has a dress code but doesn’t tell you what it is, and which makes a point of refusing to serve ketchup with French fries, which for some reason it serves despite being an Italian restaurant. (I see a pink door, and I want to paint it black.)

There’s the potato restaurant, which serves only potatoes, and there’s the Sri Lankan restaurant run by two white guys, which wouldn’t matter except that it unfortunately confirms the stereotype about white people and flavor. Sure, a lot of the food is good, but I prefer it without the self-conscious “concept” nonsense.

The real issue, though, is the homeless problem, which is not exaggerated here. I was in New York City recently, I’m in D.C. often, and I’ve always felt that this narrative of urban decline was exaggerated. However, I did not feel that way in Seattle.

These are not down-on-their-luck people begging at a corner or sleeping against a building. These were groups of people, some of them obviously high on something or other, that causes them to bend over and stare intently at their shoes—not great drugs. Every time I got a whiff of weed, in comparison, I breathed a sigh of relief. Normalcy! I’ve never been on a city street where the homeless people were actually a large percentage of all the people out on the street. Usually it’s an empty street you don’t want to end up on.

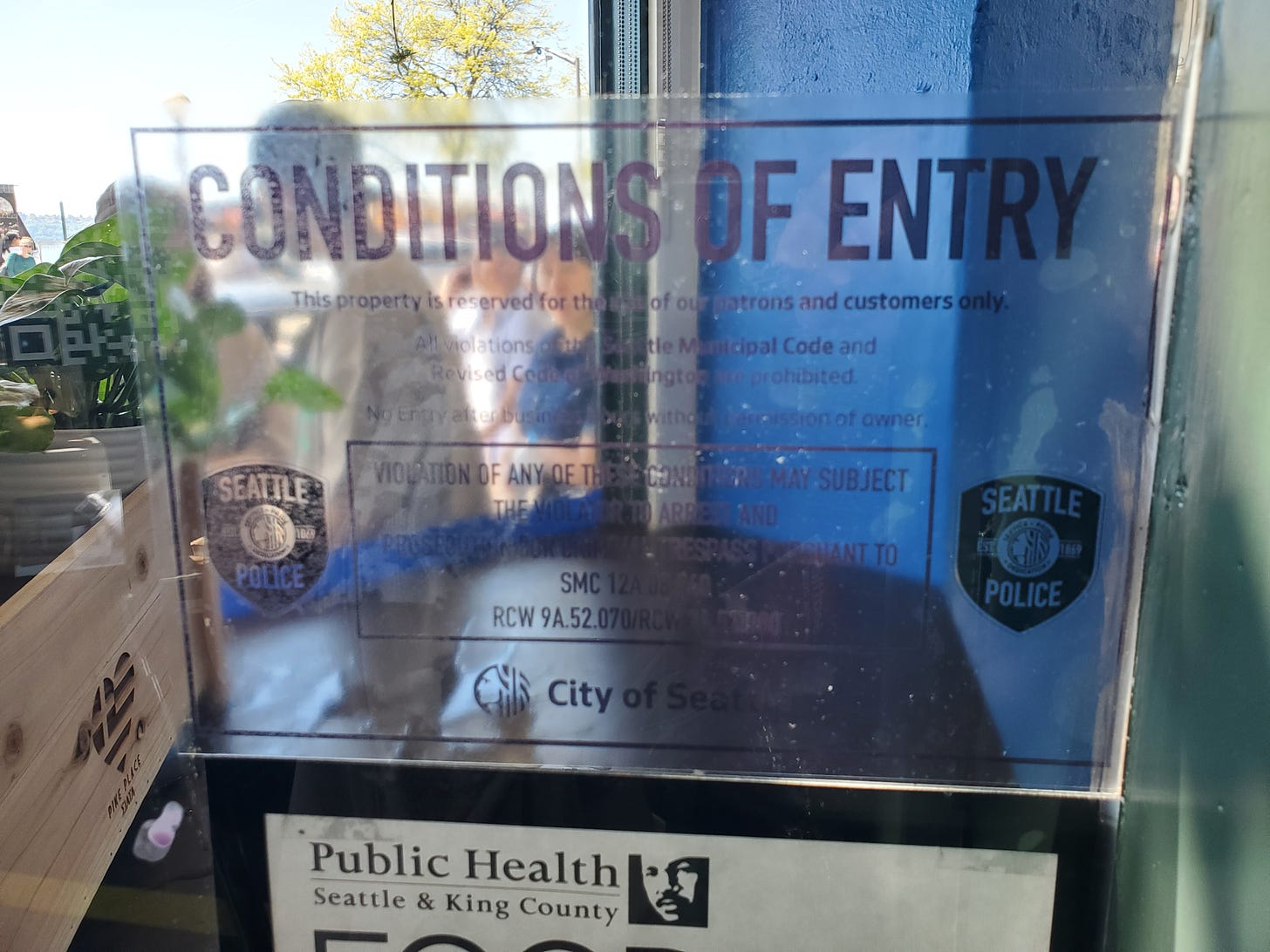

The problem is apparently enough that there’s a police program to help business owners fight “trespassing,” resulting in almost every business having an Orwellian “Conditions of Entry” placard at the door.

Of course, they have that right, just like they can demand shoes or a shirt for service, just like they can call you a bitch for buying their biscuits. But it strikes me as one of those ways in which the implied social order becomes harder-edged when social problems go unresolved.

Now nobody bothered or threatened us—homelessness is not crime, after all—and nobody even asked for money. It was more alarming than that—as if none of them even saw us. It’s shocking to see a parallel society of desperate, troubled people, with nobody doing very much about it except to wish them all to prison on the one hand, or to pretend that tolerating this kind of inhumanity is a mark of broadmindedness, on the other.

If every big city were like Seattle, I’d sound like the Boomers.

But Seattle did remind me of Europe in one respect: there wasn’t enough air conditioning.

Really, though, I’m not joking about the homelessness. This was my first time seeing this problem at this scale. Hell, it was probably my first time seeing people high on hard drugs. Maybe I’m sheltered. Maybe I should be more aghast at their condition than my own feelings at having to see it. But you can’t handwave it away. “Alcohol is a drug too,” or “People with means shoot up at home,” or “they’re more upset at being in their position than you are at having to see them”—it just doesn’t ring true. The best possible reading of these responses is that they mistake human charity for good public policy.

It’s shocking—scandalizing, really. I guess I think it’s a kind of vice to harden yourself to it and go about your day. People think saying “Oh, the city is fine except for the tent encampments and open drug use a block from the city’s main tourist attraction” is sort of like saying “It has a few dents and scratches, but it still does the job!” But it’s more like asking, “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?”

I wrote about some of this once, trying to take in the complexity of the issue—in particular, I thought about the distinction between preventing people from ending up on the street versus getting people on the street back into normal society—but what sparked that piece was this conversation, which I thought of again in Seattle:

I had an interesting conversation with my best friend as we floated in his backyard pool on a recent New Jersey evening, behind what was practically my second childhood house.

He was telling me about a road trip to California, which was supposed to involve a few days in L.A. When he and his girlfriend got to the city, he wanted to see if Skid Row was really real. This was at the height of the pandemic, and, as my friend discovered, it was realer than ever.

Every city has homeless people, he said; that didn’t bother him. But this was “tents as far as the eye could see,” a phrase he used twice to emphasize the extent of the desperation—which he saw expressed there in homelessness, of course, but also in petty crime and prostitution.

Two things really stood out, he said. One was that it felt as though the law had broken down there, like it was a parallel society where the normal rules didn’t reach or apply. The other thing was how separated it was from the obscene wealth concentrated just next door. He would see a stylish woman dressed in designer brands and a homeless man walking past each other on the sidewalk as if the other didn’t exist. The homeless man wasn’t soliciting; the woman didn’t conspicuously avoid him. They were just living in separate universes on the same little stretch of street.

I asked my friend if he’d been reading commentary about California from right-wing sources, which tend to exaggerate how severe these problems are in the state. He said he hadn’t read anything; these were just his unfiltered observations and impressions. He and his girlfriend left L.A. the same afternoon they arrived.

That’s what’s so uncanny and unnerving about it. You’ve got all your tourists and hip locals queuing up for the fake “first Starbucks” or walking around with their food from the market—gotta say, the homemade Greek yogurt gelato for $7 a cup is pretty damn good—right on the same block as the woman with the gangrene arm and the man screaming profanities at nobody and the guy shuffling along the sidewalk occasionally spitting on the ground, but at a little too high of an angle to want to get too close to him. You feel bad for these people, but you also know you should keep moving. You feel like you’re being forced to treat fellow humans as animals. Simply existing in such a space imposes a psychological discomfort beyond, and less selfish than, fear.

As I’ve said before, add kids to the mix, and suddenly this becomes untenable.

I’ve definitely been in cities that are more dangerous statistically, and more run-down visually and physically, than Seattle. Heck, lots of places I go shopping and driving around are more dangerous than Seattle. But perception is reality, and while homelessness and the public disorder that can go along with it is not the same thing as crime, it is unreasonable and self-defeating to insist that such problems are essentially inherent in the city itself. That’s an argument for people who don’t like and don’t care about the city to make, not for people who do.

Then there are the indicators of social progressivism: the safe space and anti-harassment signs, the Gaza protest with the woman crying “Intifada!” into a megaphone. And how all of that also simply coexists with a more visible and immediate problem.

This isn’t really what I wanted to write about Seattle, but it’s the only thing I really can write.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

The short version of it is that the homeless "advocates" want homelessness to be as visible as possible so they encourage very public encampments, gatherings, etc. It used to be that the encampments and loitering were fairly discreet but that all changed around 2015 (after the police shut down a very large encampment under I-5) and got far worse with COVID when shelters were ruled too cruel. You don't really see it in the residential neighborhoods because that would lead to a more meaningful pushback. The end goal seems to be to scare off enough rich people that rents go down but pre-Amazon Seattle was never like this and I doubt the progressive activists would enjoy it. You really see how quickly things can break down in a city with a populace that used to be famously law-abiding.

(The ban on solicitation is the one law police bother enforcing, so that's why no one asks for money. You have to go to Portland if you want that experience.)

Why Seattle should be talked about. . .

Seattle has a high transit mode share and is only one of only six major US cities in 2019 with a driving commute mode share of less than 50%. It's the only such city without a significant fixed guideway network. They do it all with buses.