Once in awhile, I probably forget that there are folks on my email list, and certainly who happen to see my pieces online, who don’t know or have never heard some of the arguments, analogies, or facts that underlie my thinking about urbanism.

Here are a couple, for example.

One: the insight that cars make up a large portion of the noise in cities, and yet—because we take cars so for granted—we often think of that noisiness as being characteristic of cities, and not of the cars that fill them up. In a lot of ways suburbia, despite being built around car mobility, also allows an escape from the car. Think of quiet cul-de-sacs (“no thru-traffic!”), or giant box stores that almost resemble enclosed, car-free shopping districts.

In other words, the realization that the omnipresence of cars, and the twinning in our mind of mobility and people with the cars they occupy, makes it difficult to perceive the ways in which cars can (can, not necessarily do!) degrade our places.

Here’s another one I think about a lot: what we call a “car crash” is the same thing as two people bumping into each other, or a cyclist sliding on some gravel and getting a scrape or bruise. It’s just that cars amp up the cost and risk of a collision. That helped me, fundamentally, to see car crashes as something we very much choose. We choose, in designing so many of our communities around auto-mobility, to bake in a high level of danger into everyday life. Bumping into someone barely registers; crashing a car can destroy thousands or tens of thousands of dollars in property, ruin your life, or someone else’s, or even end it.

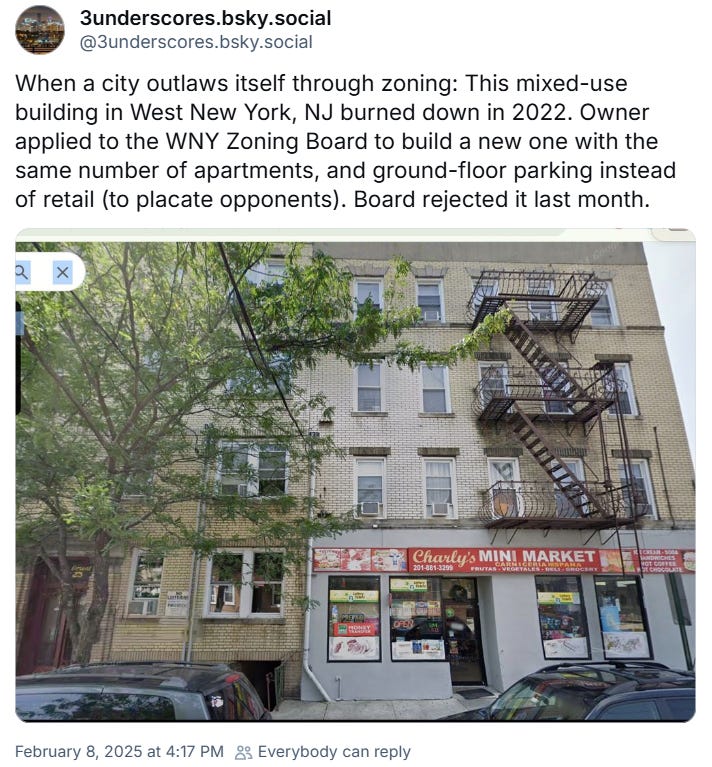

Today, I want to point out another major thing that helped make me an urbanist. This:

My understanding is that what’s happening here is that the existing buildings are, obviously, grandfathered in under whatever the current zoning code is—i.e., a zoning code will never require a pre-existing, nonconforming building to be demolished (to my knowledge—I wouldn’t be too surprised if some municipality somewhere had tried a provision like that).

But, in many cases, there’s nothing that says an existing, grandfathered, non-conforming building can be precisely rebuilt. That doesn’t mean it can’t be rebuilt, because the variance process exists, and boards have a lot of discretion—more than they should, probably. But it means that there’s no guarantee of being able to replace a structure that burns down.

This has nothing to do with writing up zoning codes for new communities, or stopping suburbs from densifying by having single-family zoning only. These are urban places which currently have zoning codes on the books which don’t even allow people to build what is already there.

It seems to me it would be pretty low-hanging fruit, but also kind of a big deal, to advocate for zoning reforms in existing cities that amend the code to say that buildings irreparably damaged or destroyed can be rebuilt as they were, probably with certain modern building-code additions. I’m sure that some codes allow this, but I’ve heard many stories from many different places of destroyed buildings not being allowed to be replaced. I believe this is a non-trivial issue.

It’s also a principle of the thing: I’m much more sympathetic to suburban NIMBYs who want to preserve the way their place is than I am to people in cities who don’t even want the city to be a city.

I wrote about this here:

One map, produced by the programmer Vadim Graboys for his website DeapThoughts.com, shows every structure in San Francisco with the city’s current zoning code overlaid. The map reveals that one third of all structures now standing, and more than half of the city’s homes, would not be permitted under the current code.

This might seem like just a bit of bureaucratic idiocy, as a lot of zoning seems. But it goes beyond that: there’s something really disquieting about a society turning on its past, altering the DNA of the built environment to stamp out what exists, turning it, artificially, into a scarce, dwindling resource. The equal parts nuttiness and scariness of this is one of the foundational things that makes urbanism feel to me like a kind of lost normal.

If you know more about zoning than I do, I’m curious if you can add to this point at all: how common is it for codes which allow less than what exists on the ground to make exceptions for burned-down buildings? Is there a common clause or provision that allows or doesn’t allow this, specifically, or is it not something the people writing the codes think about that much?

Leave a comment!

Related Reading:

Three Generations of Separated Uses

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,200 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

We analyzed our city’s beloved historic downtown against its current parking regulations alone and found that 1/3 of the existing buildings would have to be torn down and replaced with surface parking lots to make the district comply with the parking requirements. The building regulations had been fixed to permit the historic building types, so that wasn’t the problem, as in many places. It’s the other regulations like parking, landscape buffers, or pervious area or use restrictions that often kill urbanism in a more unseen and pernicious way. And that’s before Building Code and insurance and capital sources take their bites out of the apple.

They way I see it, regulations that prevent existing urban buildings noncompliant are like the government saying to a building “we wish you would just die.”

That’s a pretty messed up attitude of a government towards its economy and citizenry.

I know nothing about zoning, so can't help. I just want to express my appreciation for your setting out a couple of reasons for your being an urbanist. Great point about car noise and car accommodation, too.