Back during one of the two snowstorms we had in January, I saw this video on Twitter:

I also saw this one:

This reminds me of the insight that cities aren’t inherently loud (at least not in the present day); cars and engines make cities loud. Lots of people gathered together make noise, but usually not the kind of stress-inducing, hair-raising noise we associate with “cities.” One of the tricks of suburbia is separating human activity from motor traffic—huge stores that function as enclosed, car-free street grids; homes on “quiet cul-de-sacs”—such that an entirely car-dependent built environment feels “quieter” than a city, where it’s actually possible to get around without a car but where people are constantly exposed to car traffic!

Once you grasp this—that cities are degraded by cars despite not relying on them, while suburbia captures some of the elements of car-free urbanism while being utterly reliant on the car—you see cities differently. You no longer groan “this is the city” when tires and brakes screech and horns honk and intersections get jammed up and some jerk speeds by and splashes you with a muddy puddle (at least he didn’t jump the curb and hit you). It took me until well into my 20s to realize any of this.

The idea that car crashes and their property destruction, cost, injury, and death toll are not simply inherent in mobility is one of those similarly striking and arresting insights. If 99 percent of the trips you ever take growing up are in a car, you probably think that’s completely normal and that there’s no realistic alternative. Walking and walkability are little treats, or otherwise exotic or elitist. Sometimes on social media you’ll see folks slot concern over traffic deaths into “wokeness”—as if “40,000 Americans shouldn’t die on our roads every year” is indistinguishable from, say, “words are violence” or “I need a safe space.”

We’re culturally trained to see driving as basically inherent in doing things. And that sense of inevitability makes us blind to its downsides. A lot of urbanist ideas first sound kind of immature, trite, and slogan-y to me—and then I realize how deep they are. As I noted, “Cities aren’t loud, cars are loud” is one of these. This bit about crashes is another one.

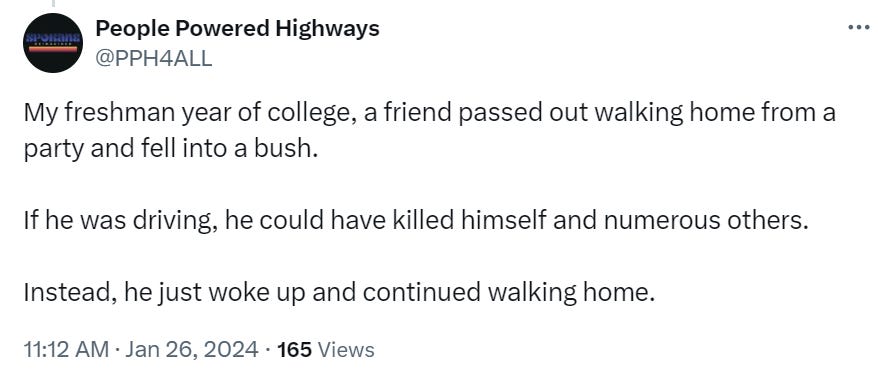

The idea that wiping out on your bike or tripping while walking or falling into some bushes while drunk is essentially a “crash”—that the automobile transforms a fairly common, mostly harmless, low-stakes event into an expensive, frightening, violent, life-and-death one—is a way of seeing this that would never, ever have occurred to me. My initial reaction would be, or at least would have been five years ago, “Oh, come on. A crash is a thing that happens when a car hits something. When you’re not in a car, it’s not a crash. What point are you even making?” And yet I can’t unsee it.

Cars up the ante of everything—the distance, the speed, the noise, the danger, the potential for violence. As I wrote about business and development in a recent piece:

Parking—and by extension, the car as the default mode of transportation—sets the minimum cost of doing business above the level of the individual. It forces the scale of commerce “up,” towards more size physically, more concentration financially, and more distance geographically. We think of the car as an engine of opportunity, permitting someone to easily move across the country or access jobs relatively far away. But the effects of the car on housing, land use, and entrepreneurship reduce the value of that mobility.

The car cannot be used as a “cheat” or a “hack,” because the car itself alters the landscape which it would help you navigate. Using the car to access opportunity ends up being a little bit like printing more money to buy more stuff. And the inflation that money-printing causes manifests itself, in the case of cars and the built environment, as this “embiggening” of scale.

Something about the car is simply not scaled to the human individual. Once you start to grasp this, you see it everywhere. This distortion is almost omnipresent but invisible—only visible in its absence, in those seemingly magical spaces and situations where the logic of the car does not set the tone.

Related Reading:

“Streets Closed to Vehicular Traffic”

Cities Aren’t Loud, Cars Are Loud

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Reminds me of the critiques from Ivan Illich. He divided technologies into convivial and non-convivial. The telephone was convivial because it brought people together in communication. The automobile was non-convivial because it disrupted human interaction and dominated and replaced the human landscape. He died in 2002 but was apparently not enamored with the internet, the ultimate tool of communication. I don’t know the details.

"A man with a car in a world made for feet is a god; a man in a car in a world make for cars is in traffic." - a great pithy line from Marc Barnes. Cars, like all things we make, absolutely change us (our habits) and our environment.