I wrote up my notes and further thoughts last week on a book talk with housing journalist Jerusalem Demsas. It went longer than I thought—which should stop surprising me, probably—so I’m doing a shorter follow-up on the rest of my notes/topics/extended thoughts.

The next one where I left off was homelessness. Most housing scholars believe that homelessness is fundamentally a housing problem, at least more so than it is a drug addiction/alcoholism/mental health problem. Those are obviously elements of why and how people end up on the street. But the key thing that correlates with a place’s homelessness numbers isn’t its substance-abuse or mental-health problems, but its (lack of) housing.

This is one of those areas where the judgment of people who study this stuff conflicts, sometimes wildly, with the impressions of a lot of regular people. It’s very easy to see someone suffer from addiction, lose their job, and end up homeless. When an expert says “Homelessness is a housing problem,” a lot of people think they’re being told, Who are you gonna believe, me or your own eyes? But what we see and what we’re looking at are not always the same. This goes back to Demsas’s point up at the top of her talk/my last piece:

Demsas opened with a point that I think people think of as being “left” or “progressive,” but which is really just…true: she said that it’s very easy to turn your life into a narrative and see your choices as determining your life trajectory, but so much of where you end up is your surroundings and your opportunities. The housing issue—which really means who can live where, in which kinds of places, at what price, with access to which schools, etc.—truly does affect our lives, and the lives of our children, in a lot of invisible ways. Ways that feel “natural” but which are downstream of policy choices. Zoning, she put it, “is about what kinds of lives are available to people.”

What you see is the addiction, the erratic behavior, maybe the public drug use. What you don’t see, at least not directly, is a housing market that bottoms out much higher up on the price/income ladder than it used to—that offers few last-resort options for semi-functional people to get back on their feet or stay housed while also struggling.

Demsas made the point about homelessness being downstream of the housing crunch. But she also identified overcrowding and sprawl as symptoms of the housing crunch. Overcrowding isn’t the same as density. Overcrowding is people subdividing houses with a bunch of roommates, or more than one family living together in a unit. Density, in terms of multifamily buildings, is how you fix overcrowding.

Sprawl is also downstream of high housing prices/too few homes in the most desirable (which is to say job-rich) places. The Arlington, Virginia housing advocates have a thing they say: one tree saved in Arlington is 50 trees clear-cut in Prince William County. Think of one of those toy squeeze-balls where you squeeze the middle and part of the ball stretches way way out. That is what happens to land use at the periphery when you restrict supply at the core.

One of the themes of Demsas’s talk and of her work at a broad level is that so many of our problems are housing problems; that opening up the housing market in job-rich places would just make so many things better. I often contend with a sort of opposite impression: that the problems you see in cities are fundamentally urban problems, and that building more housing in other places will spawn those urban problems there. In other words, the operating principle for a lot of NIMBYs is “If we build more housing we’ll end up with all the problems of the city.” A big part of what animates my work is trying to answer that anxiety, which is absolutely not always cynical or bad faith or racist or classist.

One thing Demsas said is basically, if we build it you’ll like it. By which she means that a lot of the acrimony over development is about the unknown and the imagined, and not the end result itself. This is a really, really important point. In some ways, you could say, the public input process is not discerning NIMBYism but actually generating NIMBYism—because it makes the possibility of disruption loom large. The more you delay a change, and the more veto points and choke points you design into the system, the more going through with the change feels like a big deal.

One of her data points is astounding: in 2022, 20 percent of all new homes in California were accessory units, i.e. “granny flats,” mother-in-law suites, etc.

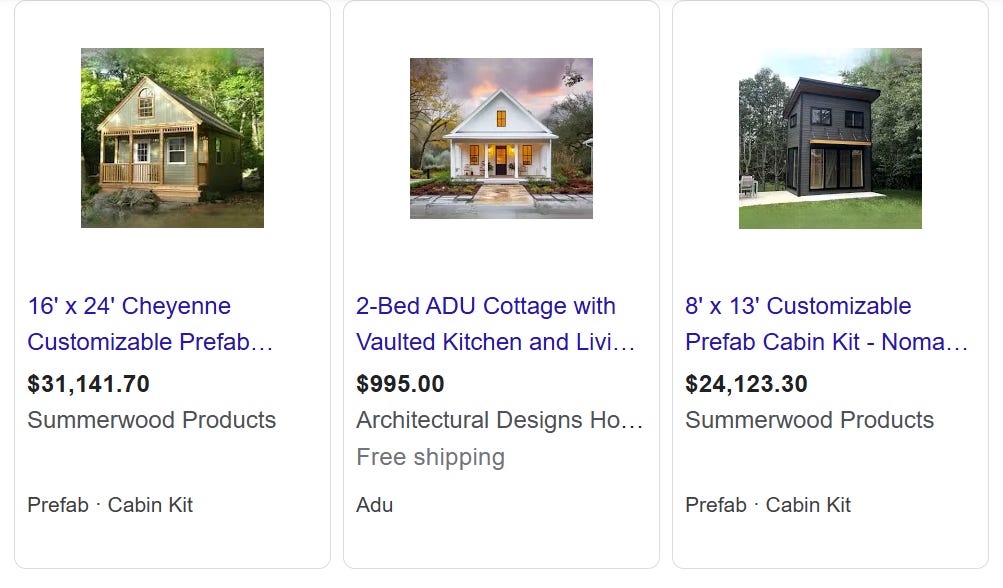

Look at what California’s (and some other states’) opening up of the ADU market has spawned:

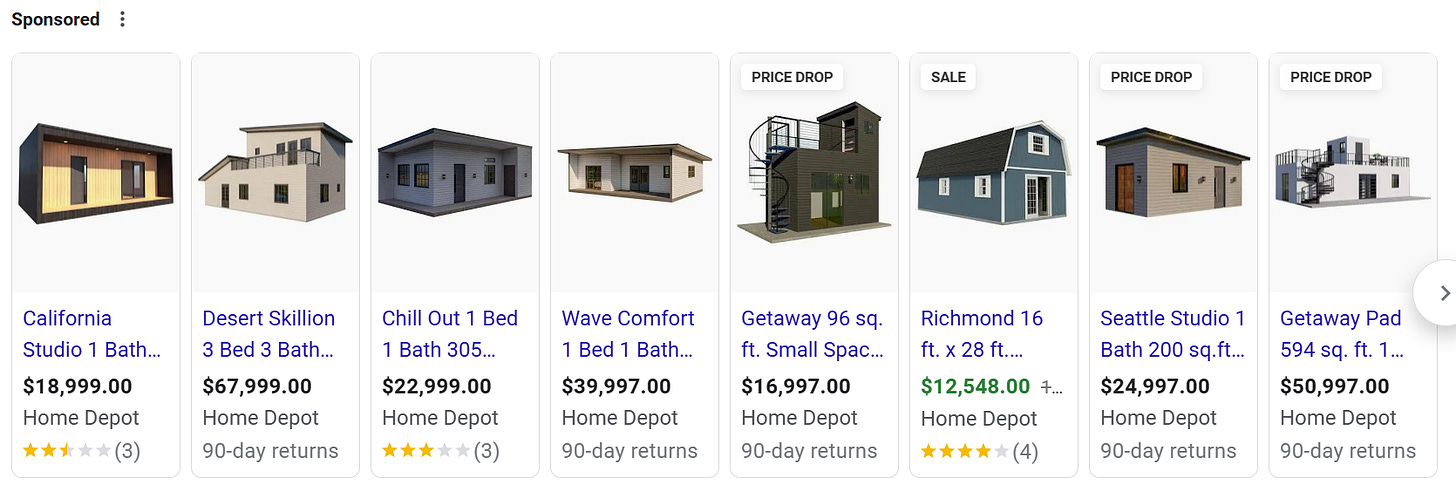

Home Depot now effectively sells houses:

Home Depot sells houses! Which means that what is/was stopping Home Depot from selling houses all along was a line in a zoning code. Is there any more spectacular example of arbitrarily, artificially impoverishing ourselves than housing policy?

Still, though, even with examples, a lot of people will default to “Well that one worked out okay, but the next one will be disruptive!” I previously wrote about the build-it-and-they-won’t-care point and the why-don’t-successful-examples-dispel-fear point. I basically think that once a thing exists it’s no longer looming, so instead of thinking “Well that thing I was unsure about turned out fine,” we just sort of stay in the “what exists is fine and what doesn’t exist I’m unsure about” mental space. There’s a reason I say that so much of urbanism is about understanding and resisting our own psychology.

One way out of this, Demsas said, could be for local governments to really focus in on legitimate pain points of new development. Things like chewed up streets, noise, snarled traffic, or even height, i.e. too-tall buildings. Take the biggest objections seriously and do that visibly and publicly. The costs of development/construction are real and concentrated. The benefits are real but diffuse. This fundamental asymmetry is a real thing. Maybe how you deal with that—as a good local government, or as a person—is a kind of test of character.

But the point is not building enough is a problem. And it’s a problem for small towns and cities as well as the big metro areas known for their housing crunches. During the pandemic, when a lot of people went to small towns and more remote places like Idaho or Montana, it didn’t take a very large absolute number of people to inflate housing costs in those places. There just wasn’t enough slack inventory to absorb a demand increase. This is a kind of analogous point to something we learned during the pandemic about hyper-efficient supply chains. Hyper-efficiency might reduce costs by reducing waste, but when something disrupts those finely tuned mechanics, you can’t do anything. You have no slack, no spare capacity. Our housing market is like that. Except chronically underbuilding isn’t really efficient either.

Then, semi-relatedly, Demsas talked about gentrification. Either in regard to gentrification discourse, or NIMBYism, or even much of the law, there is a foundational assumption that new housing is a burden to be carefully distributed. This is a fundamental, misanthropic error. The law, at least going back to the Supreme Court decision that found zoning constitutional, treats density, which is to say people, as a nuisance, a problem. This “isn’t based in anything real other than our historical understanding of what a ‘good neighborhood’ is,” Demsas said.

NIMBYism in the form of anti-gentrification might be more noble than NIMBYism of the keep-my-property-values-high-and-keep-out-the-riffraff variety, but in no case does not building anything keep prices affordable. Construction is a lagging indicator of low supply. The solution isn’t to build nothing in working-class communities, but, Demsas said, to build enough so that newcomers aren’t financially harming long-termers by bidding up scarce housing. This makes sense when you think about how many expensive places that have not kept up construction-wise are now expensive.

A final important point for left-NIMBYs is that strict zoning and a regulatory environment that makes building difficult time-consuming, and expensive isn’t just sticking it to greedy developers. Nonprofit and social housing builders are affected too. That stuff raises the costs for everyone, not just the “bad” guys.

At the end of the day, it just comes down to the fact that the housing market has to be dynamically connected to 1) population and 2) the job market. Zoning effectively severs the housing market from the rest of the economy. No feeling or argument or appeal to nostalgia or neighborhood character can overcome that. That doesn’t mean we can’t or shouldn’t plan or accommodate growth in various ways. But it means there is a certain absurdity in treating housing as a free-floating, abstract policy consideration or an optional preference.

Thanks for following along with these two sort of meandering pieces. I try to go to all the relevant events in the D.C.-Maryland-Virginia region and when one of them is interesting, I like doing these reporting-commentary pieces. And since there’s so much here, leave a comment elaborating or disagreeing, if you like.

Related Reading:

Which Housing Is “Housing Crisis Housing”?

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Addison, one of the things you seldom mention is the draconian height limitation inside WDC. Nothing can be more than eight stories tall so that the skyline of the city is not ruined. In a normal city, one would expect to find gigantic high rises at every subway stop, beginning with the city center and marching outward. That would do a considerable amount to make more housing available in the Washington DC Metro region.

Re: "In some ways, you could say, the public input process is not discerning NIMBYism but actually generating NIMBYism—because it makes the possibility of disruption loom large":

I've had similar thoughts about whether the administrative state treating new development as a big deal acts as a self-fulfilling prophecy. When virtually any additional housing is treated as a major event, with signs on the property, months/years-long approval processes, and individual public hearings, maybe it's not a surprise that people react to it as an existential issue.

Not to be overly simplistic and say that if governments gave people more freedom to build that it would just be something that happens in the same way that businesses move in and out of commercial spaces, but I can't help but wonder if we prime people to overreact.