Housing, YIMBYs, and "Luxury Preferences"

We need to build housing not just for people, but for cities and metro areas writ large

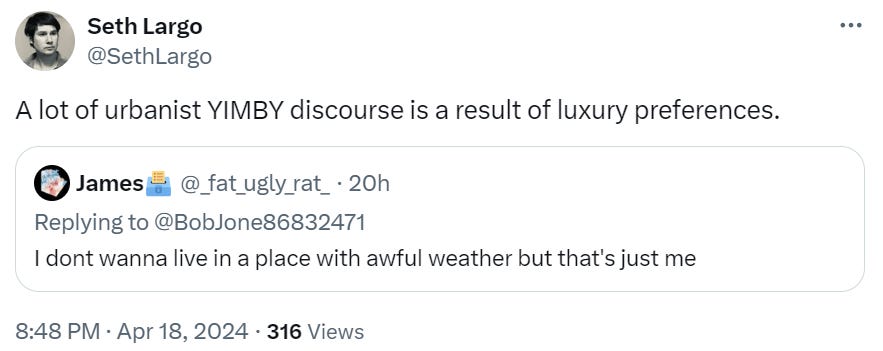

I saw this tweet the other day:

I saw it because this fellow then asked me, “@ad_mastro What’s your rebuttal here? The history of humanity is a history of people moving for greener pastures instead of whining about why they can’t live where they want.”

Well, thanks for asking!

And you won’t be surprised that I have an answer. I’ll start by saying that I don’t particularly care for the individualist YIMBY framing that goes something like “I should be able to live anywhere I want.” This is not really consistent with reality or history. There have always been and always will be more affordable and more expensive cities, and neighborhoods within those cities. There will always be people who are too affluent to need or qualify for subsidized or affordable housing, but not affluent enough to afford their dream home in their dream neighborhood.

Building a lot more housing in lots of places may control or even bring down rents—10 or 20 percent, maybe, eventually. Something significant for people and families who are not very rich. It might return housing to an asset that generally appreciates a decent amount over time, so you can sell and trade up with your accumulated equity. It might return markets like my own in Northern Virginia to something expensive but sane—a house, for example, that just sold for a whopping $950,000 might go back to costing $600,000 or $700,000. (Even that’s an extremely high price, when you look at all the country’s regional housing markets.) Building housing isn’t suddenly going to crater housing prices.

Building smaller units might, which is a trade-off that some folks may want and others may need to make. These tiny apartments in Tokyo—less than 100 square feet—rent for somewhere in the $400-$700 range, monthly. That strikes me as something that might work for a lot of young people, for a year or two, or maybe a few. I’m not sure the folks who think YIMBY means unlocking every neighborhood at every age and income level are imagining 95 square feet of space for themselves.

All of this is to say that there probably are some 20-somethings on social media who think a spike in homebuilding is suddenly going to mean they can live anywhere at a price they can afford. And for a number of reasons, that probably won’t happen.

I can imagine, if the only YIMBY stuff I saw was this sort of “build housing so I can live cheap in Manhattan!” stuff, that I might think YIMBYs were spoiled brats. The answer—that everyone should be able to live in Manhattan because Manhattan is awesome—doesn’t quite feel emotionally satisfying. There’s some part of me—the conservative in me, I guess—who just wants to say you can’t always get what you want. Maybe I’m just traumatized from my mom singing that Stones lyric at me when I wanted something she didn’t want to get me. But I’d like to think it’s a little more than that.

This is why some folks interpret YIMBY as being about handouts—they seem to have trouble distinguishing “build more housing and raise the supply so prices come down” with “give me a house!” They’re wrong, but there are some housing advocates who in my opinion blur that line.

On the other hand, “you can’t always get what you want” or “life’s not fair” are observations about the vagaries of life and the trade-offs we inevitably have to make—like maybe living in a tiny apartment if you want a prime location. They’re not public policy prescriptions. I sometimes get the sense that conservatives think the role of public policy is to reinforce the unfairness of life, rather than to reduce it where possible. I also get the sense that we start to see the effects of our policy failures as inherent slings and arrows of life, and begin to feel that there is some sort of “cheating” involved in remedying them.

I see this in myself with silly things like using a colander and a bowl instead of a salad spinner to wash veggies. I reserve the salad spinner with its easy mechanical advantage for special days. I get used to dealing with some semi-broken implement and start to feel like it would be vaguely wrong to replace it. If you deal with adversity long enough, you make your peace with it. But breaking out the salad spinner is morally neutral. It’s using the right tool for the job. Building housing and driving down our artificially high prices is likewise using the right tool—the market—for the job of aligning our housing market with our broader economy.

There is no more “cheating” involved in recognizing the economics of land prices and building smaller, denser housing in core locations than there is in using a chainsaw to cut down a tree. Density is not political. It isn’t a culture war or an ideology. It’s simply the natural response to expensive, in-demand, scarce land. When you’re running out of room in your office, and you buy a desk hutch, or a taller bookcase, you are doing the same thing for the same reasons.

I sometimes say housing is a practical issue, not a culture-war issue. What I mean is, all of the suspicion and ideology and politicking is an overlay on top of the basic economics at play.

So. Let me now pivot a bit. If you—like me—think there’s something a little galling about “I should be able to live anywhere I want!”, what do you think the proper opposite of that is? In other words, what would it mean for somebody not to be able to live anywhere they want?

Here’s an example of what might look to some folks as “entitlement” on this question:

What would it mean, however, to say that living in New York is a luxury? To determine that the sky-high housing prices in that city, and in many other desirable, job-rich metros, are simply fixed and unalterable realities, and that the only realistic options are to work harder, or to move somewhere cheap (with fewer jobs)?

I suspect most of the folks who stop at “What a spoiled brat!” aren’t thinking about this inverse. They’re mostly folks for whom the housing crisis is not an urgent matter. It’s easy for them to imagine the issue isn’t “real”: just another complaint from the youngs.

But the opposite of “I should be able to live anywhere” is it is good and appropriate for entire cities or even entire metro areas and regions to be closed off to entire ages, income levels, and groups of people. This is not how cities work. This is not how economies work. Some will counter that the young people must make trade-offs. But the real housing advocacy point here is that zoning doesn’t even allow us to make those trade-offs. There are no 95-square-foot apartments to test the thesis that what we really want is a lot of cheap space in the middle of everything.

This is why I’m so fascinated by language and framing, and in doing what I once called here “urbanist ecumenism.”

Is “I should be able to live anywhere I want at a price I can afford” actually different in substance from “Cities must be able accommodate people at all ages, stages of life, and income levels”? I don’t really think so, yet I feel like the average person would be put off by the entitlement of the first statement while at least theoretically sympathetic to the second one.

In other words, in addition to pointing out how urbanism, broadly understood, can function as a bundle of lifestyle amenities, we must also convey how they benefit our places writ large.

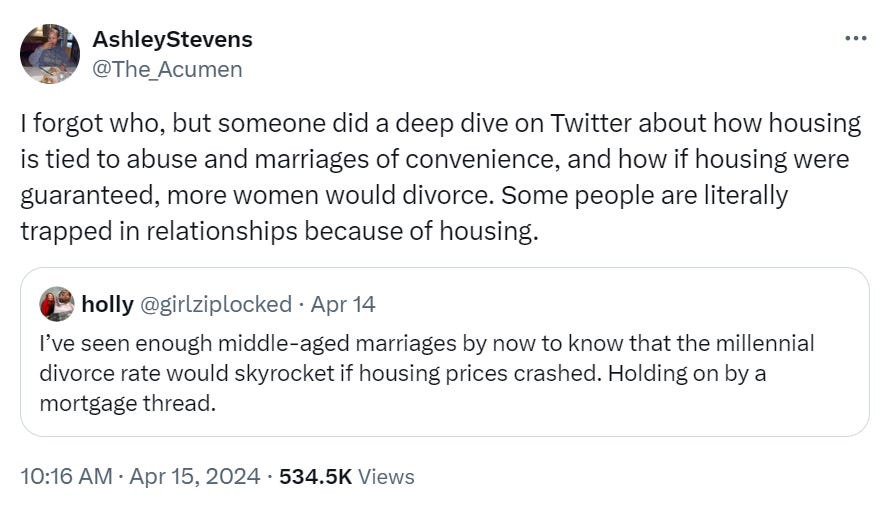

It reminds me of this:

I can hear some of my conservative acquaintances saying Ah, so you people want to build housing to help break up families! or some such. That’s a bad-faith reading of the point, but be that as it may, the thing is housing also makes it easier to get married and start a family. It makes both of these things easier, because it simply makes life easier. Our argument isn’t that housing is a subset of family policy per se, but that housing should not be an arbitrary and artificial choke point in people’s personal lives. This is one of those artificial, imposed adversities with which we’ve unfortunately made our peace.

Some people’s politics is simply the knee-jerk opposite of the views of people they don’t like. That way of doing politics is how “maybe we should build more housing in extremely expensive markets” has transformed from obvious and reasonable to suspicious and entitled.

So that’s what the actual opposite of “I should be able to live anywhere I want” is—that some cities are only for some kinds of people. That students, young singles, young families, retirees, and the folks who cook and clean and teach and police and make cities run simply have no place. No city or metro area can run like that. No city is ever rich enough and expensive enough to stop needing its working class or its starving artists or the assemblages and cross-sections of people that make a city what it is.

You can resist or oppose new housing because you don’t like the tone of some of its proponents. But you’d be cutting off your nose to spite your face. And some of us don’t have that luxury.

Related Reading:

Apartments, Ownership, and Responsibility

Still Renting After All These Years

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

The luxury goes the other way. If you live within a 20min drive or 30min transit ride of the center of a major city, why would you expect to live in a neighborhood of exclusively detached houses? That would be nice, but should there really be laws to enforce that luxury. Maybe if you don't want to see any apartment buildings, you should move further out of town.

I think that the sanewashed version is not that everyone should be able to afford every neighborhood in Manhattan, but that everyone should be able to afford to live IN Manhattan.

Like the 95-sqft Tokyo apartments, there should be enough building and diversity of options that there's an option for everything.

I liken this all to cars. Housing should be like cars, IMO. Even now since the used-car market has gone insane, it's still vastly more affordable to buy a used car than a new one. Some people prefer new cars, so they pay extra. Some people prefer luxury cars, so they pay INSANELY extra. Some people DGAF and they just ride out $500 hoopties every year or so until they break down.

But most people just buy what they can afford with some mix of features they need/want, and tolerate the lack of features they can't afford. I really wanted a sunroof on my current car, but I couldn't find any coupes with one on the time frame I was looking for, especially since my old car's registration was expiring. So I put up with not having one!

The point of building the supply isn't to magically give everyone a house. [Ed: Carmakers don't give everyone free cars just because we allow them to clear the market!] Rather, the point is to give people *options*.

Generally speaking, the auto industry tries to build as many cars a year as people will buy. They dedicate entire teams of economists to estimating that number, and they spend vast sums on advertising and relentless improvement of features in order to capture as much of that number as possible. They separate into dozens of production lines, even multiple badges, just to make sure they're catering to every single possible taste. [Ed: At no point are they doing ANY of this for charity, even when they're making "affordable" options! They simply know that their market is free enough that there is a profit to be made EVEN off of selling cheap cars to poor people.]

At one point, that more or less was the approach of the homebuilding industry. I think going back to that isn't conservative or liberal, progressive or libertarian, and doesn't even inherently necessitate "YIMBYism" -- _except_ to the extent that NIMBYs forced YIMBYism into existence in the first place...

... no, it's just *sane*.