Here’s a bit from a previous piece at this newsletter, titled “Housing and Deservingness.” I was responding there to people who reply, when I talk about housing affordability, something like, “I just think people should buy what they can afford.”

People aren’t necessarily arguing that this has to do with deservingness per se. I’ve heard the argument that (paraphrasing) “I don’t necessarily think that it has anything to do with deservingness; it has to do with the idea that if you want something, you pay for it. In other words, not do you deserve it but can you afford it? That’s economics, not moralizing.”

Fair point. But in many ways that’s a distinction without a difference. It depends on how you see those prices, and what you think they mean. Because some people aren’t just saying “if you want a nice house you’ll have to afford it.” They seem to be saying, even if they don’t say it outright, something closer to “It would be wrong to take actions to lower housing prices, because that would be giving people something they haven’t earned.” In other words, home prices for many people effectively serve as proxies for deservingness. They effectively view freeing up the housing market or the land-use regime as if it was giving a handout—a fallacy many such critics would readily see in any other context.

I want to think some more about this. What it seems like to me is that some people view prices not as market signals, but as metaphysical facts or revelations: This thing is valuable, and lowering its price would be to devalue it. Not in the obvious economic sense, but in some vague moral sense. In other words, “What you can afford” is a fixed thing, not an accident of market or regulatory forces. And wanting to lower prices is the same thing as demanding something—another fixed thing—that you can’t afford.

You could, I suppose, make a sort of argument along these lines—that housing prices should be high, because housing is some sort of reward, and the actual prices in the real world reflect the “real,” metaphysical, price. This is essentially a religious belief, but it could be argued. But any such argument disappears when you consider how we talk about prices in (almost) any other context.

Consider, for example, gas prices. The only people who think gas should cost more are environmentalists. The “normal” view of gas prices is basically that they’re always too high. Lowering gas prices is a key political activity: strategic petroleum reserves, pressuring OPEC, opening up drilling, various direct and indirect subsidies to the oil industry. The legitimacy of using market and even government pressure to lower gas prices is basically just assumed.

Or look at how we talk about grocery prices. Again, the idea that some groceries should cost more—that supermarkets and farm bill subsidies and factory farming externalize and conceal the “real” costs of food—is a minority and sort of ideological opinion, again coming from people like environmentalists. They’re probably correct, but the “normal” opinion is that those side effects are okay because cheap groceries are an obvious boon to the consumer.

The notion that lowering prices for these goods and expanding access to them would be morally questionable, let alone wrong, strikes most people as absurd. Yet that exact idea comes up when housing advocates talk about housing affordability.

In effect, the minority “ideological” view of prices you find with gas or beef has become the “normal” view for housing. And the “normal” view that housing is a necessity, and should be built, and should be affordable, has become the minority “ideological” view.

I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again: the very fact that there are “housing advocates” or “YIMBYs” is a symptom of a very deep problem. Something so universal and basic should not require this level of advocacy or particular identification. Can you imagine if people who believed in farming or grocery retailing were called “food advocates”?

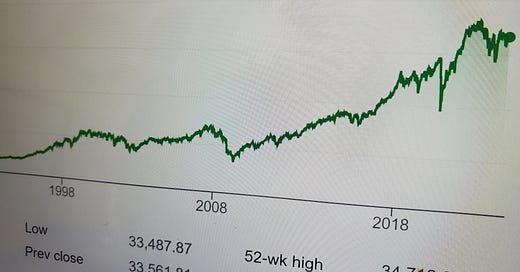

But there is one other thing you can buy that people generally talk about this way. Stocks!

Homeowners talk about housing prices the way stockholders talk about stocks. This dynamic is (broadly) referred to as the “homevoter hypothesis,” after a book by William A. Fischel arguing that homeownership and its interests heavily shape local government. A house is the largest asset most people will ever own, and they have an obvious interest in maintaining its value.

That isn’t wrong. But what is weird is how that economic self-interest morphs into a moral argument: how the fact that lowering housing prices might hurt some people’s investment turns into the judgment that young people are entitled for wanting to be able to afford housing—and that, like not rewarding a toddler for a tantrum, it would be wrong to give the entitled young people what they demand.

I think it’s important to understand people’s arguments and logic, so that you can understand how they arrive at their conclusions. But it’s also important to recognize when you aren’t dealing with an argument, per se, but an ex-post-facto rationalization.

I know I knock conservatives here frequently, but that’s because they’re the folks I grew up with and interact with most (I didn’t really even know left-NIMBYism was a thing until I got on Twitter.) And so, it reminds me of something you sometimes hear about controversies over voting rights and voting access: something like, “It’s good to make it harder to vote, because that selects for people who really care and are invested in our democracy.”

In other words, the adversity is not merely a side effect of trying to make the process more secure; it is the point. Or at least, that’s how the argument goes. I do not think many people really believe this. I think they probably just don’t object to making voting harder (which, for a variety of reasons, intentional and not, often selects against Democratic voters.)

These are strikingly similar arguments. In both cases, you take something obviously good and widely considered good; artificially restrict it for matters of raw self-interest; then construct a moral argument which characterizes the good thing as too good or too important to make easily available. And, finally, cast those who want more of the good thing as entitled, lazy, or asking for a handout.

In other words, when people talk about “building character,” “life’s not fair,” “school of hard knocks,” “beggars can’t be choosers,” pop open the hood and look for the self-interest underneath. These are not arguments at all. They are cynical attempts to conceal entitlement with a veneer of social concern.

Now, of course, homeownership and its economic interests are not partisan. Often, you can hardly tell the difference between a socialist and a right-winger when it comes to housing. As long as homeownership is the norm in America—and, to be clear, I have no problem with it—homeowners and housing advocates will to some degree be at odds.

But the expectation that housing prices, like stock prices, should always go up, is an antisocial expectation arising from a broken status quo. It is not a moral revelation.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 600 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

> Some people view prices not as market signals, but as metaphysical facts or revelations: This thing is valuable, and lowering its price would be to devalue it. Not in the obvious economic sense, but in some vague moral sense. In other words, “What you can afford” is a fixed thing, not an accident of market or regulatory forces. And wanting to lower prices is the same thing as demanding something—another fixed thing—that you can’t afford

This seems to me a specific instance of a much more general mistake, which is that people are unaccustomed to thinking about humans as embedded in a large and extremely complicated network of essentially institutional-psychological hacking techniques, meant to enable humans to co-operate in enormously large-scale complicated ways despite of having behaviors and subjectivities prewired for much smaller societies.

In default human society, resources are gained and held by convincing other people that you deserve them on a very individual granular level. This works acceptably because the group has relatively simple and easy-to-understand objectives and everyone is around to directly monitor everyone else's contribution to the group. Therefore, if a person persistently complains, with all apparent sincerity, that they are unable to live within their resource allocation, the most likely explanation by far is that they have an exaggerated impression of their personal worth and need to be psychologically checked back from their arrogance.

Attempt to apply this to capitalism and you get obvious nonsense, but it seems intuitively plausible because the alternative correct explanation requires first absorbing an enormous amount of fairly obscure and counter-intuitive information, and the path to finding that information is littered with people who honestly think they are doing so but are really just repeating the simplistic tribal nonsense from one side or the other.