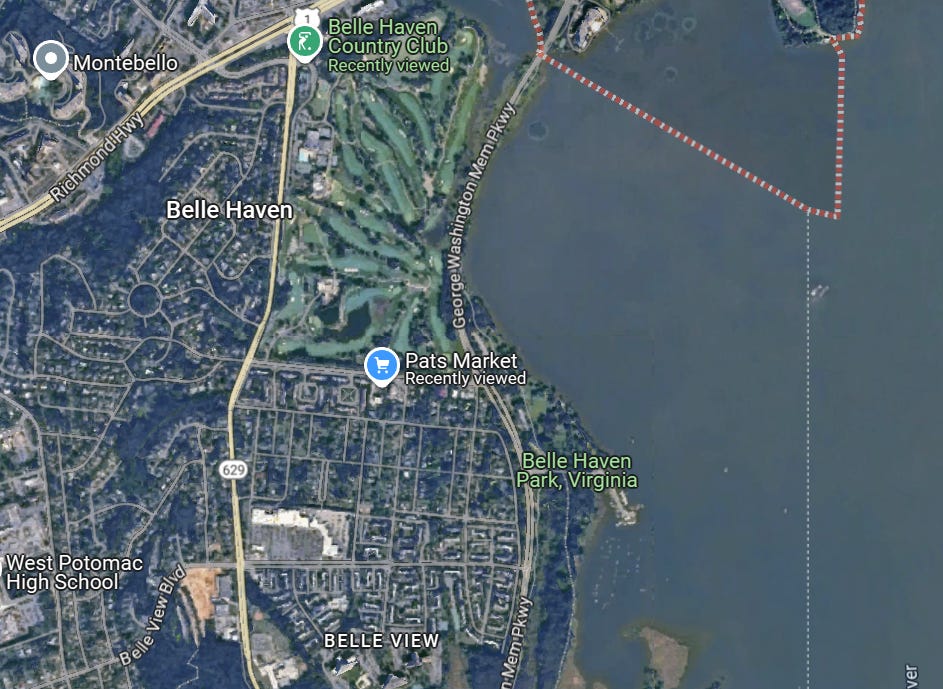

We’re taking a look today at a residential neighborhood, south of the city of Alexandria, Virginia, right below the Pat’s Market icon:

You would assume—as any motorist passing through this little suburban enclave probably would—that this was one of many postwar subdivisions that went up in this area. Or maybe late prewar, like many of the region’s streetcar suburbs.

You would not likely guess that 1) this neighborhood dates back to the 1800s, and 2) it used to be home to more than one factory!

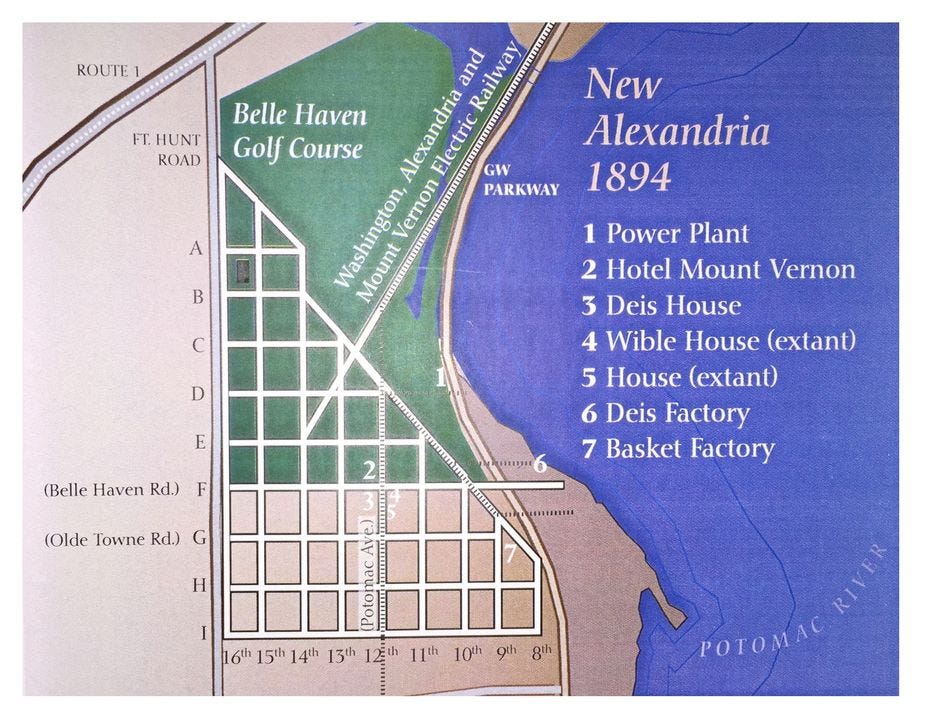

This is New Alexandria, a new town formed for both residential and industrial (manufacturing) purposes by a group of businessmen in the early 1890s. New Alexandria was formed not only alongside the electric streetcar, but by the same people:

Led by Griffith E. Abbot, a doctor from Philadelphia, a group of businessmen from Pennsylvania and Alexandria built both the town and the railway line. In 1892, Abbot, along with Luther W. Spear and Jacob K. Swartz, arrived in Alexandria. They signed on Park Agnew, a shipping magnate of Scottish descent who rose to become one of Alexandria’s most respected citizens. His ambitions extended to the political arena when he ran for Virginia’s Eighth District of Congress in 1887 (he lost to Fitzhugh Lee, second son of Robert E. Lee and 40th Governor of the state).

Given its industrial aspect, it’s really more of a failed new city attempt than it is a typical suburb, though today it’s just a purely residential suburban neighborhood. Streetcar operators sometimes built homes and neighborhoods as well, and often built amusement parks and other attractions along the lines to promote ridership. Factories is pretty uncommon.

However, New Alexandria never really took off:

That year [1893] the Wooden Ware Company signed on. 125 workers manufactured splint baskets.

New Alexandria’s detached location had advantages and disadvantages. Recruiters touted the fresh air, cleaner water, and less-crowded conditions. Alexandria fire and police serviced the town, since it was within one mile of the city limits.

At the same time, the Fire Department was almost two miles away. Fires destroyed the Deis Furniture Factory, the Carson Handle and Spokes plant, and the hotel.

Later on the streetcar went bankrupt, and by the 1930s, there was not much left. The earliest aerial imagery available, from 1949, shows a pretty sparse grid.

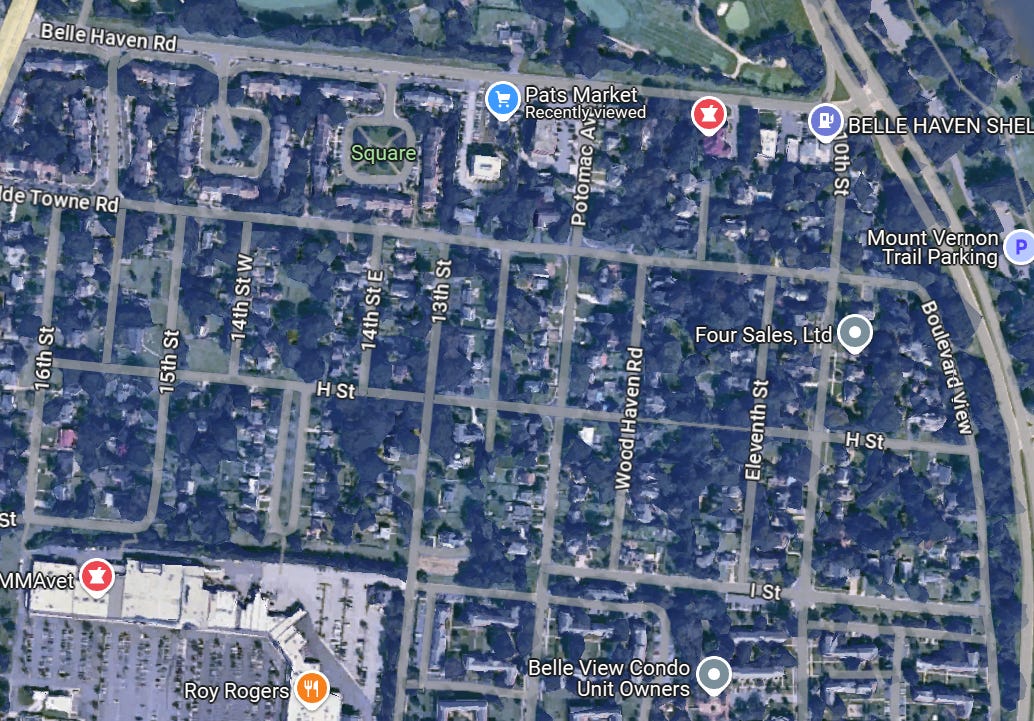

As the postwar suburban boom took off, that grid was filled in again, and as you can see from this zoomed-in current satellite image, there are plenty of homes in the erstwhile New Alexandria today:

That golf course north of the old town bought some of the town’s initial land, too. Here’s a map of the full grid overlaid on the modern boundaries:

Here’s a 2001 Washington Post article on the remnants of New Alexandria. It’s partially quoted in the blog post which the blockquotes above are from. Someone is quoted in 2001 remembering when that Pat’s Market store (now itself closed) operated under a different name in the mid-1930s.

What a perfect example of invisible history right there to be discovered anew.

Related Reading:

A City’s a City No Matter How Small

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,200 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Great historical example that I did not know about. Hit me up for some citations on the history of industrial development if you are interested in reading more. I did not start to understand this phenomenon until I read a story about the redevelopment of the Highland Park, St Paul (I am not finding the article which included a history of its original development). Present-day urbanists romanticize former street car systems. The service would not meet the standards of a present-day transit buff. While streetcars expanded the range of commuting, they did not expand it much by present-day standards. The residential enclaves were still located close to the factory, even if they were beyond a comfortable walking distance. In Houston, most factory workers were probably walking to their jobs, even as late as 1880. In Warner's study of Boston, streetcars were not affordable for factory workers until electrification. Another factor: how many factory workers returned home for meal breaks? If so, they weren't streetcar riders.

Very cool - I've worked in Old Town Alexandria for many years and had no idea that Belle Haven originated that way.

On a related note, 3 major buildings being destroyed by fire is a sobering reminder of the risks our ancestors faced. It's easy to take containment of commercial structure fires for granted after ~60 years of sprinklers being mandatory in new buildings, but that obviously wasn't the historic norm.