The other day I had a piece at Discourse Magazine, out of the Mercatus Center. I’ve made the general point before, over the years, but I think I’ve finally gotten it just right in this piece.

A little preface. What inspired me to write this was a drive out to Winchester, Virginia, during which, on my ride back home, I drove through a couple of very small towns. One of them was the tiny village of Boyce, which looks like this, including this plain building with a grand parapet/false façade, and a train station.

I found this very interesting: the bare outline of a city that might have been. When I got home I looked up Boyce on Wikipedia. And I found an excerpt from a fascinating—and unlinked, uncited—newspaper article from 1912. Here’s Wikipedia:

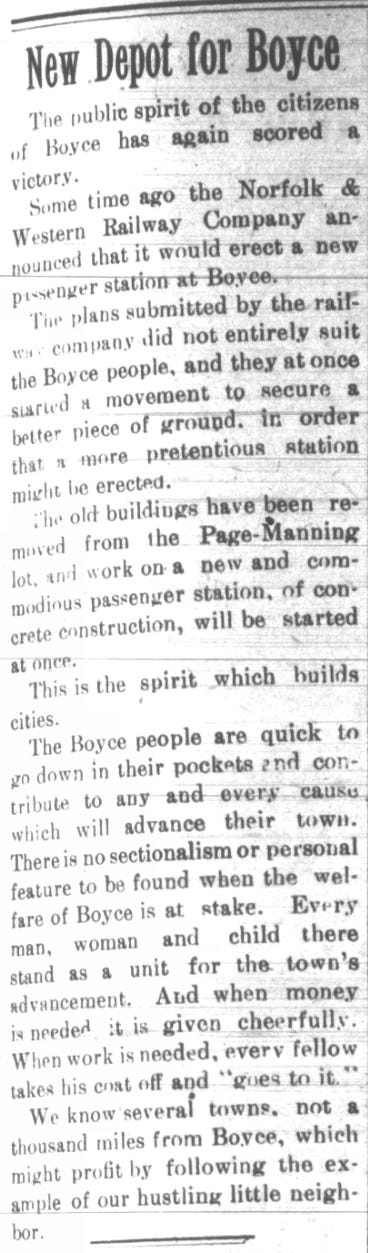

A December 11, 1912, article in The Clarke Courier entitled “New Depot for Boyce” states:

“The public spirit of the citizens of Boyce has again scored a victory. Some time ago the N & W Railway Company announced that it would erect a new passenger station at Boyce.

“The plans submitted by the railway company did not entirely suit the Boyce people, and they at once started a movement to secure a better piece of ground in order that a more pretentious station might be erected.

“The old buildings have been removed from the Page-Manning lot, and work on a new and commodious passenger station, of concrete construction, will be started at once.

“This is the spirit which builds cities.

“The Boyce people are quick to go down in their pockets and contribute to any and every cause which will advance their town....”

This is the spirit which builds cities.

Is that a sentence anyone today would think of writing in reference to a rural village of 300 people? And would anybody living in such a settlement today agitate for a bigger train station?

This was a piece of evidence proving my intuition that the way we think about towns and cities today is very ahistorical—that the largely cultural divide between “small towns” and “big cities” is basically a modern innovation.

But first, I needed to confirm that the newspaper article was genuine. I searched various bits of it on Google, but no hits—either it wasn’t digitized, or it wasn’t real. So I emailed Boyce’s official email, and asked if anyone in the town hall could help me out. Someone there responded quickly, and told me that the libraries in Richmond and possibly Winchester had microfilm archives of the Clarke Courier.

So I started an online chat with the main Winchester library, and their receptionist directed me to archives. I emailed archives, and they were able to point me to the Clarke County Historical Association, which had digitized archives of the Courier. (Not searchable text, just scanned images.) That was good enough. I searched for the right date—Wednesday, December 11, 1912—held my breath…and there it was!

There’s something satisfying about (digitally) holding a piece of evidence in your hands that proves something almost unbelievable. And that unbelievable thing is that the desirability of growing and getting on the map was more or less taken for granted. This is the polar opposite of today’s NIMBYism.

And what it shows, not just conceptually but literally, is that Boyce is not a distinct thing called a “small town”—it is, or was, the first iteration of a city. And with that I wrote this piece for Discourse.

When scientists find a piece of evidence that does not fit a hypothesis, two things can happen. Either the evidence, upon further study, does in fact turn out to fit into the hypothesis, or it voids or alters it.

It is a widely held “hypothesis” today that what we call the “small town” is a sort of lifestyle amenity; categorically, we tend to think, it belongs to the suburbs or exurbs. And both the suburbs and the small town stand against the “big city,” an entirely different, and perhaps slightly frightening, creature.

But this taxonomy may be wrong in a fundamental way. Yes, it is a roughly correct accounting of how we think about towns, suburbs and cities today. But it is mistaken about what the small town actually is, in an ontological sense. (Disclosure: I’m Catholic, and we use words like this.)

A place like Boyce is the evidence which jams the hypothesis. What the small town is, in essence, is an embryonic city. And what the big city is, in essence, is a small town all grown up. They are the same creature.

I write, in particular, about how these became cultural distinctions, with all kinds of culture-war baggage and grievance, which obscured our urban history:

Discussions of cities, towns and suburbs tend to be cultural, as do so many of our contemporary debates. Cities, in a circular argument, are where “city people” live. I wrote once about Staunton, a small city in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley with a beautiful, classically urban downtown. I praised Staunton’s architecture and urban form, but somebody replied that I was barking up the wrong tree. It isn’t Staunton’s buildings or land use that make it great, the commenter wrote; rather, it’s the patriotism and religious faith of the people.

Perhaps. But I find it curious to see people—inhabiting a town whose old commercial blocks are visually almost indistinguishable from those of Brooklyn or Philadelphia—insisting that “the city” is not an actual thing with characteristics, but a vague idea. Our town is not a “city,” because we do not like “the city,” but we like our town.

But it makes very little sense to define a city based on a nebulous cultural outlook; it makes much more sense to focus on the land use and development pattern. If you strip away the culture-war overlay—“coastal elites” and “flyover country,” debates and conspiracy theories over “15-minute cities,” identifications of “cities” and “suburbs” with political ideologies generally—you will find no evidence that there is actually any such thing as a “small town,” as we currently conceive of it.

Finally:

If you look at the history of towns and cities, in the 18th and 19th centuries, you will not find any clear demarcation between those settlements which we now call “cities,” and those which we now call “towns.” You will really only find urban settlements, which grew or shrank or stagnated or died for any number of reasons. You will find large, lovely civic buildings; the mixing of housing and commercial uses; a variety of housing options; and dense settlement patterns. And you will find these bits of urban DNA in places ranging anywhere from a few hundred people to hundreds of thousands of people; while these places’ sizes may differ, these characteristics are constants. The places which went on to become big cities did not collectively choose to do so, and those which never grew beyond the scale of a town or village did not decline to become cities.

There’s more. Read the whole thing.

This single newspaper article is not an aberration. I wrote about this on Twitter, and people offered more evidence in the same direction.

One person, in Springville, Utah, replied, “In 1895 my small city boasted of ‘a population increase of over 25% against any other city’s 16%. With this magnificent showing we hope incoming officers will look well to maintaining Springville’s reputation.’”

Another person searched the phrase in a newspaper database and found this:

Plus four more instances of that phrase, just in 1912!

Now, did people debate particular projects? Did people lament changes, demolitions, traffic, crowding, etc.? I’m sure they did. Those tendencies are natural. But nonetheless, something resembling today’s YIMBYism was simply the default understanding of how human settlements worked. Of course we want a train station, and a grand one at that. Of course we want our population and economy to grow.

Again, it’s almost difficult to read these old newspaper articles and not wonder if you’re being pranked. I read “December 11, 1912” over and over, making sure it didn’t really say “April 1.”

That article doesn’t say, “In a surprising twist, the residents of the quiet, peaceful village of Boyce have banded together not to stop the extension of rail, but to welcome it—and, what’s more, to demand even a larger station than the railway is planning to build.” There is nothing at all to suggest that this is unusual, or anything other than obvious. That is such a departure from today’s default views on development that it makes me think I am reading about a different civilization:

Today, when we talk about “towns” and “cities,” we make the same error as the paleontologist who accidentally categorizes a baby dinosaur fossil as a small dinosaur, and an adult fossil of the same species as a large dinosaur. There’s almost something spooky here: When I look at a small town today, I feel a little bit like an archaeologist who finds a strange artifact and puzzles over what its use might have been….

Some time between then and now, we underwent a revolution, which not only transformed American land use, but also wiped out the memory of America’s urban settlements, and the mindset which built them and understood them as such. America’s small towns today—to return to the religious analogy—are something like the old cathedrals and archbishoprics of the Church of England, inherited from Catholicism but no longer meaning quite the same thing. They are in some sense historical artifacts, all around us yet revealing a vanished world.

We may never build in exactly this same way, because our economy is very different. And the car probably demands some changes in land use. But this old spirit is recoverable. It isn’t just about land use, per se; it’s about devolving power and scale, letting people build things and do business, letting them be stewards of and participants in their place.

What we did some time in the 20th century is we outlawed this pattern, wiped out its memory, and then used that suppression as evidence that nobody wants it or mourns it anyway. It is true that cities fell deeply out of favor at that point in time. But perhaps the age of suburban sprawl will turn out to be a mistaken blip. Meanwhile, the work of urbanists is fundamentally the work of rediscovery and restoration.

Related Reading:

America’s Urban Heritage: Culpeper, Virginia Edition

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 600 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Thank you for writing this. It puts into words a feeling I have long had. I was really into American history long before I found urbanism in college. I have long struggled with a sense that we lost something truly great about the past times where virtually everywhere wanted to *be* somewhere. It was prosperous and productive and worthy of bragging to build a railroad or a new town hall or a paved street or some sign that you were living in the next big place.

"Devil in the White City" details this late 19th century obsession and adoration for dynamism perfectly. St Louis wanted to beat Chicago for "biggest Midwestern city". Chicago desperately wanted to show it was a competitor to New York and not a cold, small burned down has-been. Dozens of other cities all wanted the prestigious title of having had figured out how to handle millions of tourists and hundreds of thousands of temporary construction jobs in a race against time. Now it is a generationally-defining event to get cities with good jobs to begrudgingly allow some new houses to replace parking lots and shuttered storefronts.

I grew up in a small town which does usually come with the benefit of being instilled with a little sense of wonder at growth. It was the talk of the county for almost a decade that the old bowling alley was going to be converted into an In-n-Out. But outside of the wonder of a new fast food chain, or a new store (we were equally impressed when the 8 years of planning and negotiating brought a Costco to the county seat) you just don't have that feeling that growing and getting bigger, while challenging, is good.

Much is made of the southwest and red states for being "better" on land use than California. I think there are specific examples where this is true (quick, someone mention Houston) but you see most of the planning apparatus is there, the cities have just not yet run out of nearby virgin land and highway funds. I'm sure rezoning and upzoning Dallas and Phoenix and Florida will be just as hard when their strip malls struggle and their housing is no longer so cheap. What does seem to make those places (or at least the one I now call home, Las Vegas) different from coastal liberal cities is that there is a much stronger air of celebrating growth. Overwhelming, the people of Las Vegas are happy that we are poaching Oakland's teams (conveniently for me I moved from the bay area at the same time, so they are coming with me) and California's housing money (though people are increasingly blaming Californians for all their problems and the traffic on I-15.)

I have to wonder how we can re-ignite this desire to grow, to be big, to be better and to achieve things in the cities already in great positions to do so. That's my hope with the YIMBY movement and the fledgling "supply side leftism" that I see trying to establish itself. Let's make a better, bigger world.