Most people won’t drive an hour to take this photo:

But I’m not most people, and I love putting this idiosyncratic work into this newsletter.

Do you know what store this is (was)? I knew the name, but I didn’t necessarily know the logo, and I certainly didn’t think there were any of them left just sitting vacant like this.

Here’s the whole entrance. Note the URL in the bottom left, which had only fairly recently been registered! It still works, too, because the name was acquired and used to brand a new online-only store.

Here’s the whole building:

This is an old Montgomery Ward discount department store, rebranded “Wards” in the chain’s final years. They were originally a full-line department store along the lines of Sears, but later focused in on a Walmart/K-Mart style version of the brand—one of many such chains that failed in the 1990s/2000s as Walmart aggressively expanded and consolidated this retail segment.

This is one of the only, if not the only, Wards locations to remain completely untouched, ever since it closed with the chain in 2001.

This vacant store was the erstwhile anchor of the eponymous Ward Plaza on the outskirts of Winchester, Virginia. The sign and name remain. As do a few tenants.

What convinced me to drive out here was, first, someone else’s more or less identical photo of those door handles on a Virginia Facebook group. “Oh wow, I want that photo!” I thought. Retail is one of my longtime interests, and finding a frozen-in-time location of an old-school chain like Montgomery Ward is striking gold.

And then, not long after, I saw a news item in the Winchester Star about the sale of this old shopping plaza to a new owner who intends to demolish it and redevelop the property.

So, at long last, the whole aging, half-empty thing, a semi-living piece of early suburban history, is destined to become a mixed-use development.

That’s a good thing, pretty much full stop. This is a deeply underutilized property in an area that is seeing some housing pressure—including from the D.C. metro area—and is seeing sprawling subdivisions popping up. Meanwhile, a lot of older, inner-suburban properties sit like this, partying like it’s 1950.

Or 1964—that, from the Winchester Star, is when the plaza opened: “Ward Plaza, anchored by a popular Montgomery Ward department store, was Winchester’s first shopping center when it opened in 1964.” (My emphasis.)

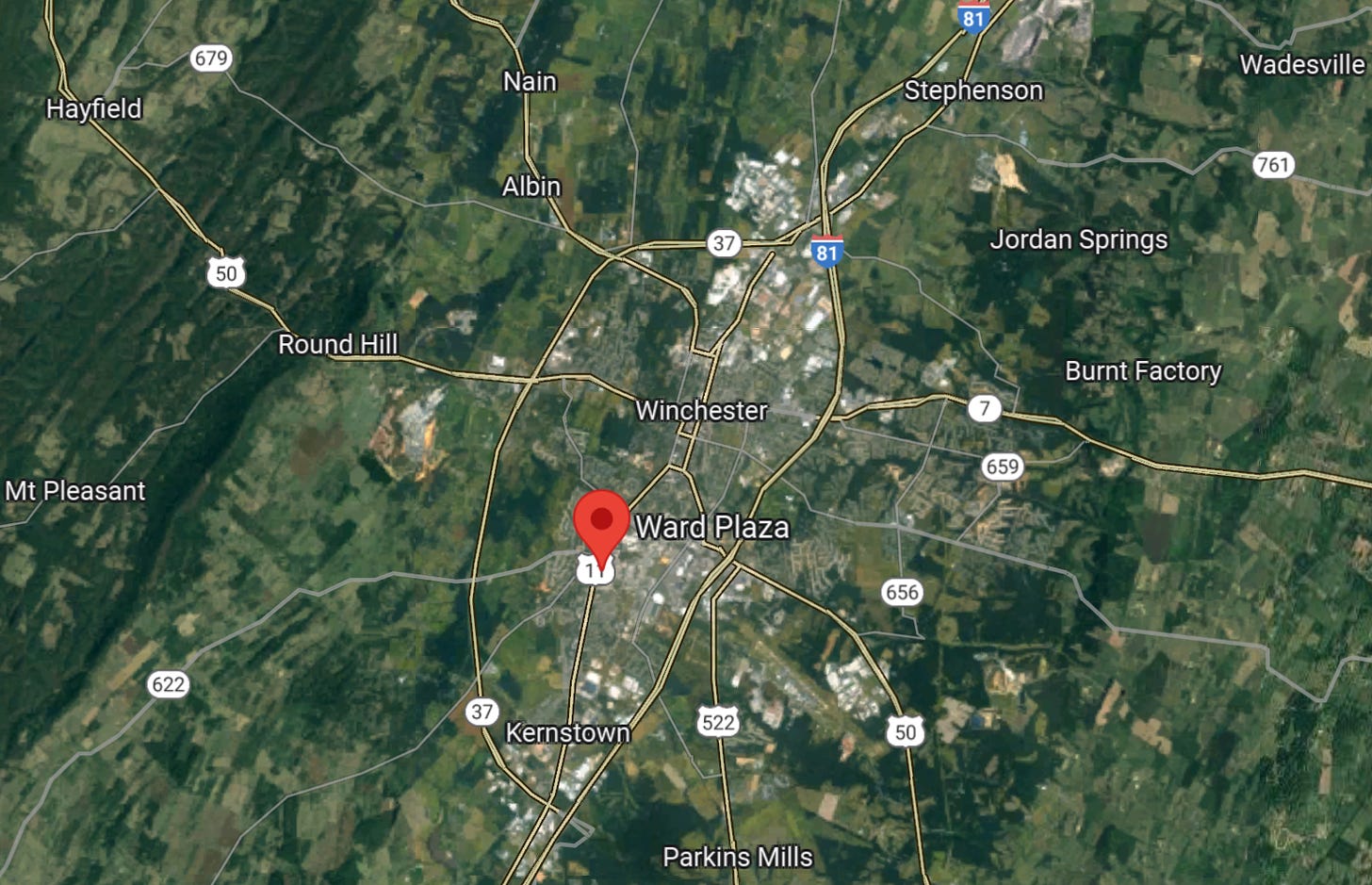

Here’s the whole Winchester area, with Ward Plaza marked:

It’s relatively close to downtown because it was built relatively early in the suburban era. You can see newer development radiating out further. (Given that the first suburban-style shopping center only arrived in the mid-1960s, this is all relatively recent, unlike the D.C. suburbs, which date back much earlier.)

This is one of the weird and distinctive things about suburban-sprawl land use, and one of the tip-offs, in my view, that there’s something economically unnatural about it. Which is to say, unnatural in terms of human behavior.

You see this pattern of the oldest or earliest properties in the suburban periphery being run down, neglected, unchanged, almost fossilized. And you see newer development on the edges. And when the now-aging inner properties were developed, of course, they were the “edge.”

This is a distinctly suburban pattern; you don’t see it in cities, or you see it much less. Of course, you have neglected urban neighborhoods. But the “bad neighborhoods” aren’t always the old ones; age is not a clear predictor of anything about an urban neighborhood or a city. The city doesn’t radiate out in this pattern of build, neglect, abandon, build more, whereas that is pretty much encoded into the design DNA of suburban sprawl.

Among other reasons, because of the rigid zoning regime, the decline of these old properties does not automatically trigger redevelopment, as it might under normal circumstances. Unless the problem is that we’ve developed too much land, making any particular piece of land too worthless to develop intensively. (Strong Towns has argued that this is why so many magnificent urban buildings were demolished in the 20th century: suburbia cratered land values, undermining the financial basis for dense urban development.) Depending on the economic situation of a place, either one of these might explain the decay or underutilization of seemingly prime properties.

There is really quite a lot here. I’ve hardly covered it all, but I’ll leave you with this point: if an outcome doesn’t make sense, dig in to it and ask why. It probably reveals a distortion that we don’t explicitly think about much.

Uninhabitable ranch houses selling for $2 million? Dense mixed-use development going up at the edge of a metro area? Semi-abandoned commercial properties a stone’s throw from the urban core? They’re all outcomes—distress signs, warning signals—that follow from our attempt to force housing and land use to conform to unnatural constraints. They are not unlike the economic oddities or absurdities that emerged in the communist planned economies of the 20th century.

All that from a set of door handles. (And by the way, I kind of want those door handles.)

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 600 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Enjoyed the read. Spotted this pair on a tire shop in Phoenix, Arizona. I believe it was a Montgomery Ward Automotive Center in a prior life.

https://flic.kr/p/2j4bZw9

You should get the door handles. I am not sure what you would do with them, but...!