We Do It Because We Don't Want To

Urbanism, persuasion, and separating behaviors from preferences

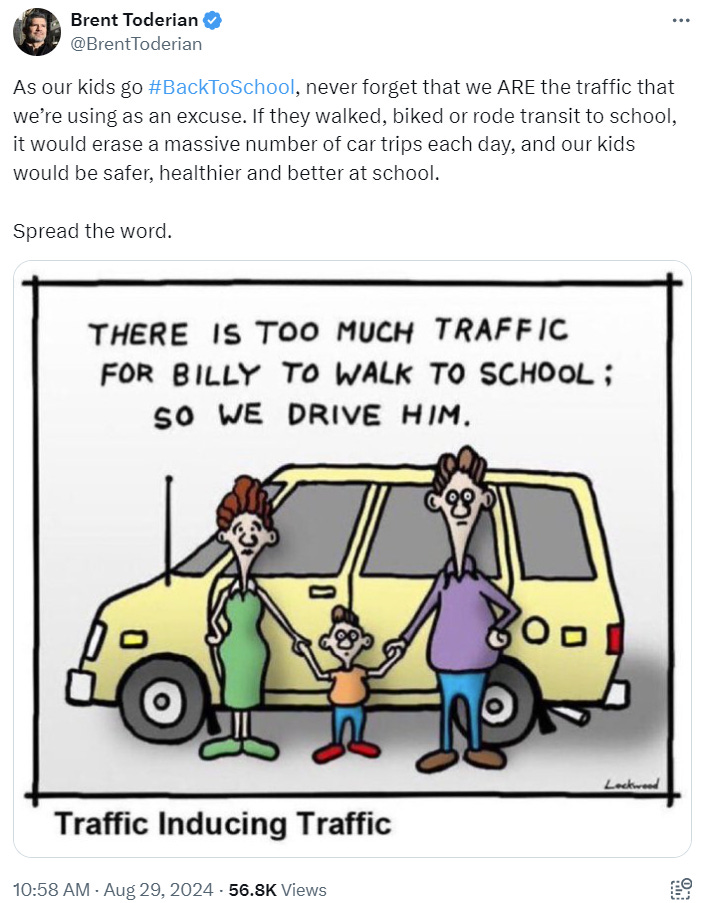

I saw this tweet the other day:

As usual, for these kinds of pieces, I have the obvious and the more abstract reaction. The obvious one is, yeah, of course we drive if it isn’t safe or convenient to walk. Maybe followed by, Why else do you think we like driving? Think about the reactions you might get if you talk about how it’s great to bike in the rain or haul furniture on a bike trailer and how a little weather and exertion never hurt anybody. It just doesn’t compute for a lot of people. Sometimes people perceive your cheerful description of your choices as an argument against them.

But the more abstract point is, you can’t necessarily determine people’s preferences from their behavior. “They do it because they want to do it” is not always a valid conclusion. Sometimes the truth is, they do it because they don’t want to do it. Looking at the school drop-off line and concluding that everybody must love it would be like concluding that everybody in East Germany must have loved queuing up for cabbage and stale bread.

The thing is, a lot of people may not even themselves realize that their behavior and preferences are distinct; or they may not have the language to describe that divergence; or they may not have any expectation that it could ever be resolved. And so even while on some level they would like to walk their kid to school in the morning, that possibility feels so remote from their everyday life that it doesn’t even assert itself as a preference.

It—the bundle of social joys and everyday conveniences of urbanism—might even feel like some kind of lazy escape or shortcut. I suspect a lot of us try to understand our hardships and frustrations as worth something, as markers of maturity. Some urbanists look at the parents lined up in their comfortable climate-controlled SUVs and see privileged, spoiled people. I see many people laboring under something they’re not really aware is or could be optional.

This is why so much of urbanism for me is about communication, discernment, perception: in a lot of ways urbanism is an unfamiliar answer to a question many, many people are asking and don’t even quite know it.

I wrote, a few months ago, about seeing America’s anti-urban commentary differently: “Think of how many people say something like, We might stay in the city if there was less crime, or if we could afford it, or if the schools were better… This isn’t a preference against cities. It’s a preference for cities as they could be.”

That phenomenon of car-dependent land use in turn encouraging car trips, in turn making the car not a convenience but a requirement, cannot be taken as evidence of an affirmative preference. Maybe some people like the things they have to do. But when they have to do them, it can be hard—even for them—to tell.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,000 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

I love this reframing and think it applies broadly to so much of our daily life. We don't necessarily love highly processed foods- we literally don't know any alternative. We don't love our careers but can't imagine making money outside of our chosen field (or even questioning the value of money at all). When somebody presents an accessible, viable alternative, we suddenly can't live without it, but we can't always imagine the alternative on our own.

This is a fascinating thought experiment. Keep sending out these threads. Some parents in the schoolhouse lineup love their cars. They just washed the red Mazda. They love a purring engine, the assurance of comfort, climate control, splendid brakes, and nimble handling. The cockpit of a new vehicle is an awesome chamber. Especially delightful for a lazy sally across the Great Plains on an empty highway. There's more to America than the schoolhouse pickup line.