Thoughts on the Meaning of Freedom of Movement

Traditional urbanism and public transit had no political valence well into the 20th century

Since a whole bunch of you have just signed up for this newsletter, I’d like to write a little intro for you. I originally came up with the name, The Deleted Scenes, to refer to the bits and pieces of my magazine articles that don’t end up in the final piece—didn’t fit, the idea went off in a different direction, etc. This post is one of those posts, a follow-up to something I’ve published in a magazine. I worked in magazines for several years, and now freelance and write this daily newsletter full time. So your signing up and reading is very much appreciated!

Most of what I write here has something to do with the built environment—urban and land use policy, commercial architecture, housing, illustrated pieces on walking around or exploring small towns or other interesting places, etc. I sometimes write about other topics, like old technology, video games, consumer issues, retail, and more.

This post is in my primary category, and bounces off a piece I wrote for The New Atlantis back in fall of last year on attitudes about public transit in America.

I wrote, in particular, about how high-speed rail is a sort of shiny object for a lot of left-leaning folks, while others are skeptical of the cost and scale of these projects—and also whether they would actually serve ordinary people in the communities they would run through. I argue that we should think not about cars/transit/high-speed rail per se, but rather about how to enhance freedom of movement for all Americans. An error that many on the political right make, and honestly anybody who unselfconsciously drives almost everywhere, is to conflate the car with freedom of movement itself:

There is a tendency in American culture, and particularly of conservatives, to associate the automobile driver’s freedom of movement with political liberty. Despite the ubiquity of trains, subways, and streetcars in our history, some view motorists not only as entitled to public roads and free parking, but as morally superior to transit users.

I’m also likely to annoy some conservatives with this observation, which I stand by completely:

Aside from these philosophical critiques, suburban car drivers sometimes reject transit for more troublesome reasons, worrying that the expansion of urban transit will also mean an expansion of (by their reckoning) the wrong kinds of people into their neighborhoods — the homeless, criminals, or simply minorities….By this logic, limited freedom of movement for those without cars is a kind of insurance against them having access to suburban neighborhoods. (emphasis added.)

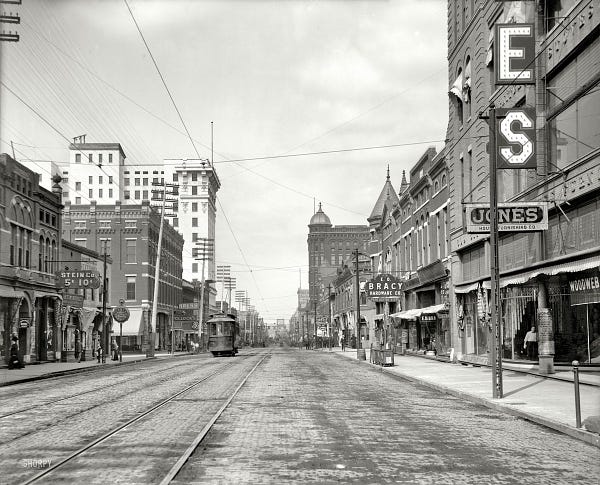

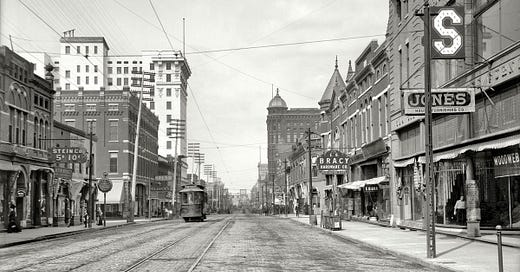

A lot of this, however, is scrambled—at least it was scrambled for me, despite having no background in any of this before three or four years ago—when you realize the extent to which America was once an urban nation. Look, for example, at this picture:

All of the standard talking points on these issues—you can’t raise kids in cities, cities are just for affluent young singles (or for poor people, go figure), Democrats want density and Republicans want privacy, blah blah blah—none of it really makes any sense when you consider that tons of places, even very small settlements surrounded by countryside, once looked like this. Traditional urbanism and public transit had no political valence well into the 20th century.

And, I argue, one way to recapture that spirit might be to eschew mega-projects like high-speed rail, to devolve scale and complexity, and to focus instead on more humble and local projects, whose utility is more obvious and, as the essay is titled, closer to home.

There’s another point here, which doesn’t require you to have any particular commitment to urbanism, but rather to allowing more economic freedom—including for folks like service workers:

Our economy depends on the ability of workers to live within reasonable commutable distance of all kinds of jobs. An expensive metro area still needs the janitors, parking attendants, and restaurant workers it has priced out of its housing market. Yet expensive cities are often no more hospitable to allowing low-income workers to commute there than to live there. How much growth — and how much tax revenue — is foreclosed because of weak transportation systems? How many opportunities for an entrepreneurial person with an idea and some cash are rendered unworkable?

This, for me, is a huge argument against restrictive zoning near urban cores. Many of the inner suburbs that are now quite expensive, like Arlington, Virginia, were once the countryside. It may have made sense to build them out mostly with single-family homes back then. But while zoning has locked much of Arlington’s land area in the 1950s (or, really, the 1930s), the metro area’s job market and population have exploded. Whatever it may mean for equity or affordability—and it isn’t good for those things either—single-family zoning, in places like this, artificially decouples the job market from the housing market.

Combined with less-than-stellar public transit, this is the result:

Consider Washington, D.C.’s Metro system, which currently ends service at midnight, even on weekends. This often forces the hospitality and service workers who power the city’s bars, restaurants, and nightlife venues to pay for rideshare to get home, whose prices are now elevated over their already expensive normal levels. In May, when the Metro was closing even earlier, some workers waited for hours after their shift for rideshare prices to drop below $50. The patrons at late-night venues are likely to have either a designated driver or the cash for an Uber home. Many live in the city. But service workers, priced out of the city’s housing market, and working too late to catch the final train, have fewer options.

You might not guess it from any of this, but I actually lean towards the political right. However, a lot of what I write is trying to get fellow right-leaners to think differently about urban issues, like land use (less sprawly), transit (better), and housing (more). Of course, there are also progressives who effectively take the same skeptical positions, even if their language differs.

I often explore these and related issues, from the point of view of someone who isn’t trained as a planner or activist. I hope you’ll check out the whole essay, and I hope my interested-layman’s take on this all has something insightful for you.

And for those of you who joined in the last week, thank you once more, and please keep reading!

Related Reading:

Taking Off the Car Blinders, Opening Your World

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive of nearly 300 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

I'm one of those new subscribers; I'd just like to say thanks so far, your essays have been very illuminating! 100% agree with you that there needs to be less restrictive zoning in the urban core. Something that Jane Jacobs mentions in "The Death and Life of Great American Cities" is the need for a stock of old buildings to promote residential density. Right now, my hometown (Omaha, NE) is experiencing a re-densification of its older areas - but it's all new construction, outside the price range of the service workers you mentioned. Also, Omaha has been chasing a new, "shiny" streetcar idea which just got approved last month and will be free for all riders, but which will run along a very high-density, mixed use corridor and will not service the low-income neighborhoods that have the hardest trouble with freedom of movement. You're right to say that such projects seem to just be shiny things that city planners sometimes like to chase, but do they really have utility for the people who need them most?

Have you ever written about raising a family in the modern-day urban core? It's something that's on my mind a lot, and would love to read more about. Thanks, again, for your writing!