The U-Turn Not Taken

Europe's ultimate settlement with the car could have been, and could be, ours

Quick note, readers: today’s piece is the thousandth piece I’ve published here at The Deleted Scenes! Go ahead and upgrade to paid for 20% off, just today! Thank you for reading and getting us here!

There’s a famous—to urbanists—story about Amsterdam in the 1970s. Today, Amsterdam is the poster child, almost the byword, for a quiet, clean European city that makes lots of room for pedestrians and bike riders. When people talk about “Europe” in terms of land use, they often mean, or you imagine, Amsterdam.

To the extent that the average person knows about Amsterdam’s urbanist reputation (they’re more likely to know about its other reputation), they probably think it was always like that, and that most of Europe was always like that. That’s fine, but those cities weren’t built for cars, while American cities—at least to a greater extent—were. This is what I used to basically think. It’s the default, inherited American viewpoint.

But it isn’t quite true.

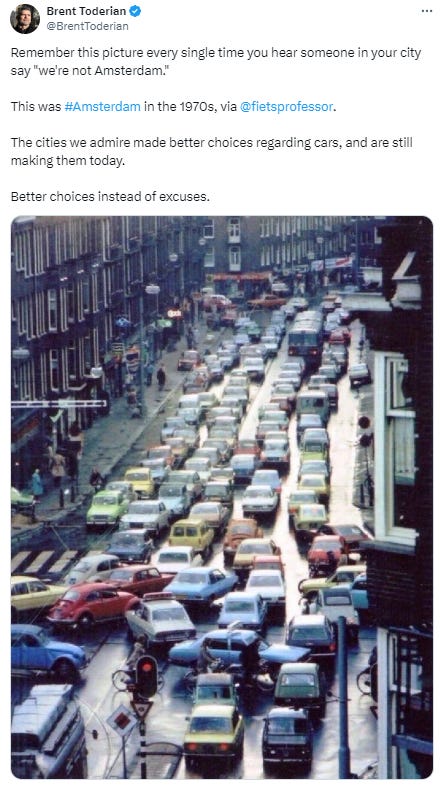

By the early 1970s, cars had deeply degraded the city. Look at this picture in this tweet:

In addition to the nuisance of urban traffic congestion, traffic fatalities reached very high levels:

In 1970, the Netherlands had a traffic fatality rate that was slightly lower than that in the US [meaning, very high]. That year, 3,200 people died on Dutch roads. Many saw this as an outrage and thousands took to the streets to protest, calling for the government to “Stop the Child Murder.” Since then, government at all levels in the Netherlands have worked diligently to improve traffic safety.

What changed in the Netherlands? Well, first we should recognize and celebrate those that triggered the changes — the thousands of people who took to the streets in the 1970s in Stop de Kindermoord (or “stop the child murder”) demonstrations. This advocacy forced an initially reluctant officialdom to take traffic fatality seriously. Activists also led the way in showing that the necessary change was in societal thinking about the role and function of streets — and they took it upon themselves to show how streets could be re-configured for safety and pleasant living. Eventually, these grassroots interventions were codified into new rules addressing how streets were designed, funded and governed. As a result, separated cycle tracks (not painted bike lanes) and other design changes that control speed on automobiles were implemented to give bicyclists and pedestrians dominant roles on Dutch streets.

A society that could still be moved by the violent death of children. The 1970s were a time when it was possible to fully see what the car had done and would do to cities, but also to remember a time before it. We’ve lost that first-hand clarity in America, but we can still learn history.

And the history says that up until the 1970s, much of Europe had gone all-in on cars and on the urban problems they brought with them. The ugliness, the noise, the pollution, the traffic fatalities. But when these problems reached a certain point, the Europeans were shocked and spurred into action. And they actually rolled back the primacy that the car had earned itself, and meaningfully circumscribed its place in the city.

In other words, contra the received narrative—that America broke with Europe at the onset of the car era—Europe and America both increasingly accommodated the car in the 20th century, but Europe chose in the middle to give up the experiment.

So what you probably think of as “European” land use/transportation—intact old cities, cars permitted but not dominant or completely prioritized, other mode shares, functioning transit and high-speed rail, a real concern for pedestrian safety, a love and appreciation of cars as machines but not a total reliance on them for everyday use—isn’t “European.” This settlement with the automobile was not inevitable in early/mid-20th-century Europe. And the flipside of that is that such a settlement was—and is—possible in America.

Let me spell it out again: both Europe and America had beautiful pre-car cities and towns. Both Europe and America embraced the car and began to reorient legacy cities around its needs. We were on the same path not until the 1920s, but until the 1970s! If the definitive divergence with European land use/transportation happened that late, I think that changes how realistic such a transformation could be in America.

The car exists, and it can’t be put back in the bottle. It can’t and shouldn’t be banned, not even, probably, from cities. But it is possible to countervail its logic, its ravenous desire for speed and space, which are incompatible at a very deep level with the city.

We know that, because it isn’t a pipedream. It has been done.

Related Reading:

Always Treat A Car Like It’s Loaded

Speeding and the Eucharistic Prayer

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter, discounted today! You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,000 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

It should be noted from the picture that while they had a super wide road, the setting is a proper city. It's much easier to roll back car dependency if your environment allows for it. In other words, Amsterdam in the 70s look much more like New Amsterdam than Breezewood, PA.

Closing Lincoln Road in Miami Beach for cars was easy. It is impossible to close any road a few blocks north of it.

And maybe you can remove I-5 from crossing Seattle (as they did with many roads in Europe), but you won't be able to remove I-30 from Dallas.

So any talk about removing car dependency needs to go through changes in urban settings. In a sense, Amsterdam (or Paris, or Madrid, or Istanbul, or Rio de Janeiro, etc.) wasn't built for cars indeed, unlike most American cities. Cars took over, but the urban conformation made it easy to scale them back.

Fascinating! I've definitely shared those assumptions about cars. I've enjoyed learning about how we can challenge our assumptions about urban design. The big problem does seem to be that many people want cities to look differently, but they don't want to personally change.

My own city, Indianapolis, has horrible public transportation, and the city's ambitious plan to create rapid bus transit has been met with fierce opposition from our state legislators, business owners who are frustrated at the requisite construction, and the seeming low-adoption of the program among passengers, because, frankly it's just not as convenient as driving.

Interested to keep learning about solutions to these problems! Thanks for your work.