Last week, I wrote about Bassett—the furniture company, and the town in Virginia, which is named for the family who also founded the company.

Bassett has lost a lot of population and a lot of furniture jobs, and the big old Bassett plant sits empty right outside the town’s tiny downtown area. The company is still headquartered there and has a small number of jobs there, but it isn’t like the old days.

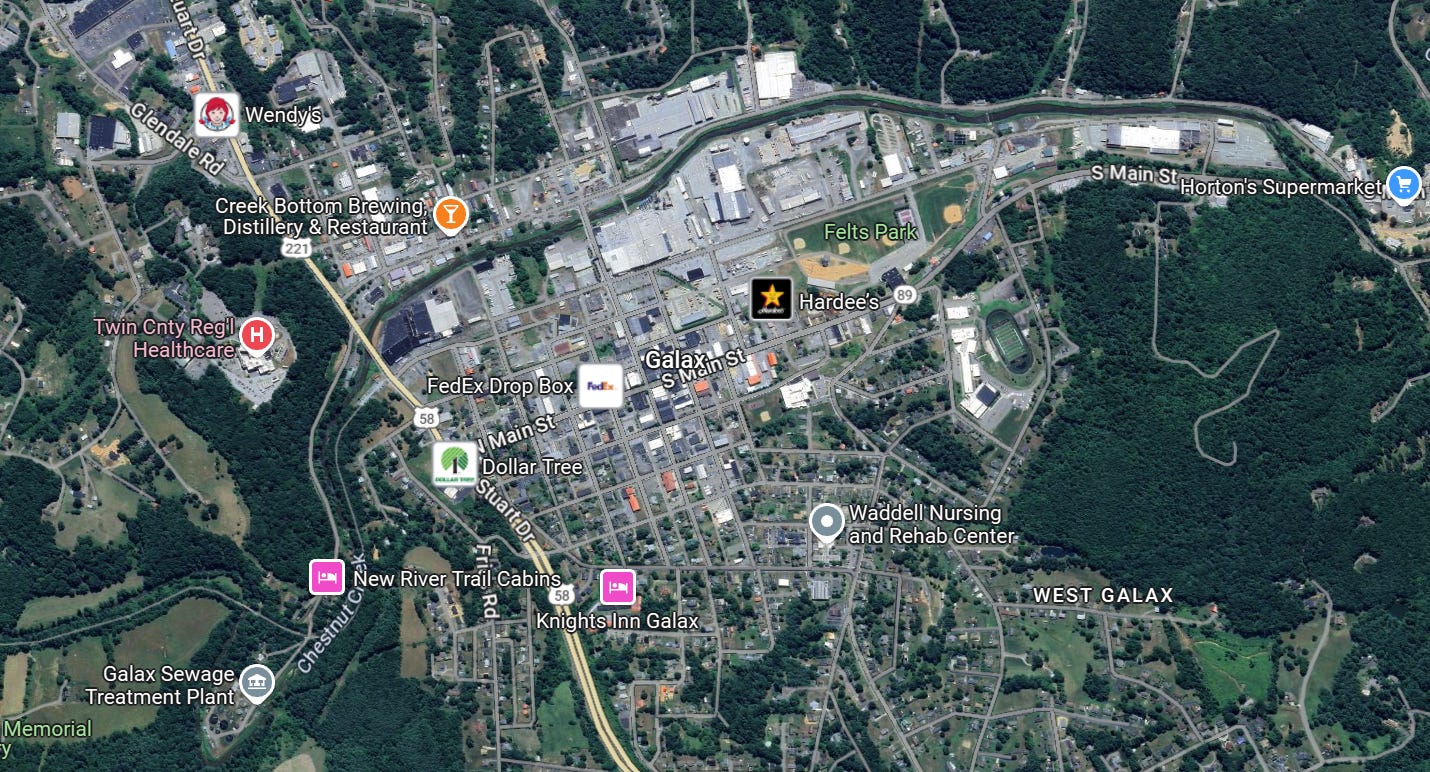

Today, I’m featuring the town of Galax, 66 miles from Bassett, and Galax’s own furniture company, Vaughan-Bassett Furniture Company. The Bassett of Vaughan-Bassett is the same Bassett who founded Bassett in Bassett! …

So you have two very similar places in the same region of the same state, sharing one founder, making the same basic products. While one of them went the familiar way of outsourcing and globalization, the other is a very different and heartening story.

In the 1950s, Bassett was home to about 3,000 people; today it’s under 1,000. In the 1950s, Galax was home to a little over 5,000, and today it’s close to 7,000. A town in southwestern Virginia actually growing between the postwar years and the present day is pretty unusual. Galax has more urban fabric, and a much larger downtown area, so it probably had more staying power because there was more of it, earlier. But that’s hardly a guarantee of economic fortunes.

It’s more than a company town, too, and furniture isn’t the only business. For one, Galax is known for instrument-making, perhaps an adjacent but distinct industry. But most importantly, the Bassett-founded company that ended up here didn’t switch to importing cheap overseas furniture. In fact, they claim:

Employing over 500 craftsmen in factories based in Galax, Virginia, we are extremely proud of the fact that 100 percent of our furniture is crafted here in the United States by American employees. In fact, Vaughan-Bassett is now the largest manufacturer of wooden adult bedroom furniture in the United States.

Most of the furniture we manufacture consists of wood solids and wood veneers grown and is harvested near our plants in the Southeast. Pine, oak, maple, cherry, ash, poplar, birch, and beech are the primary species used in Vaughan-Bassett's bedroom collections.

At one time, this would not have been unusual. This is one of those “lasts”—something that becomes notable simply because it keeps existing during a time when most things similar to it change or disappear.

Here’s a really interesting article from The New Yorker, published back in 2014. I don’t think I realized that these globalization-related closures were still happening so recently. Bassett’s Bassett-based plants only closed in the late 2000s.

The Bassett factory closings came not long after many of the region’s textile plants had closed for the same reasons. Between 2001 and 2012, more than sixty-three thousand U.S. factories closed—furniture and clothing mills, shoe and machine-tool factories. There were few places in America where the job losses felt as concentrated as along the eight-mile stretch of the Smith River that is home to Bassett, in the red-clay foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. In that area, some nineteen thousand workers in the region were displaced between 1990 and 2013.

The situation in Bassett is unusual, though. Unlike in many mill-towns-turned-ghost towns, Bassett workers know about a group of workers similar to them, in a town much like theirs, that has managed to thrive despite the effects of globalization.

And there was another point, in the 1980s, at which a Bassett family member went from Bassett to Vaughan-Bassett:

That town, seventy miles away, is called Galax. It is the workplace of John Bassett III, a onetime heir to Bassett Furniture who, in 1982, was elbowed out of Bassett—the company and the town—by his older brother-in-law, Bob Spilman, who had visions of his son, Rob, succeeding him as C.E.O.

There, John Bassett resurrected a struggling furniture company called Vaughan-Bassett. In 2003, he organized the filing of what was then the world’s largest petition against China over “dumping,” the illegal practice of selling exports to the U.S. that are priced lower than the cost of their materials. He won. (I document the battle in my forthcoming book “Factory Man.”) Vaughan-Bassett ended up with forty-six million dollars in anti-dumping duties, a development that allowed John Bassett to keep his factory going at the same time as his relatives in Bassett were closing most of theirs. (Bassett Furniture received $17.5 million in duties but used most of the money to buttress its retail expansion.)

Today, Vaughan-Bassett is an outlier in its industry—one of the last bedroom-furniture makers left, as well as the largest. Vaughan-Bassett employs seven hundred people in Galax.

This might have something to do with these divergent stories: “Vaughan-Bassett, in Galax, is privately held; Bassett Furniture is public.”

And what a different world the ‘90s was:

Economists, politicians, and others had predicted that trade liberalization, in the nineties and aughts, would help American workers whose wares would theoretically be exported to China’s growing consumer class.

Here’s a cool program in Galax, offering grants to building owners in town to restore old facades. It’s chicken and egg, investing in a place and having economic vitality. They’re lucky, whichever way that goes. I don’t know if the folks in this town are actually called Galaxians, but it sure looks like another world.

Related Reading:

Why Can’t Every Day Be Like a Christmas Market?

How Far to the City That’s Not on the Map?

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Great post! Appreciate the research.

It’s interesting to think about how the fortunes of whole towns could turn out so differently based on the choices (and perhaps luck) of individual businesses. There are probably stories like this in small towns all over the country.