Technology, Delayed Gratification, And Cities

Urbanism is a physical manifestation of human needs

So this piece—“A Time We Never Knew,” on smartphones and society—made the rounds recently on social media (which I guess is ironic). I read it with a bit of trepidation, because I never know what the provenance of an independent writer is, and often this stuff veers off into…questionable territory. (I’m thinking of the “LED lightbulbs are a symbol of the decline of the West” guy, for example.)

But this isn’t one of those pieces. It expresses what I think a lot of people my age feel about the ubiquity of phones, cameras, apps, location tracking, the internet, social media—all of it, the constant connectivity and the difficulty of extricating yourself from the things themselves, and also—a distinction with a difference—the expectation of them.

This is the core of it:

There were hard times, of course—the ‘90s weren’t all bliss; no era is. But the world we inhabit now is so markedly different. New technologies cheapen and undermine every basic human value. Friendship, family, love, self-worth—all have been recast and commodified by the new digital world: by constant connectivity, by apps and algorithms, by increasingly solitary platforms and video games. I watch these ‘90s videos, and I have the overwhelming sense that something has been lost. Something communal, something joyous, something simple.

Of course, we have so many material comforts and conveniences now. I can follow the news all over the world, Google any statistic I want, write on Substack, and WhatsApp someone on the other side of the world. All for free. In a world like this, it’s easy to see why older generations might not understand why Gen Z is struggling to cope.

But God, that loss—that feeling. I am grieving something I never knew. I am grieving that giddy excitement over waiting for and playing a new vinyl for the first time, when now we instantly stream songs on YouTube, use Spotify with no waiting, and skip impatiently through new albums. I am grieving the anticipation of going to the movies, when all I’ve ever known is Netflix on demand and spoilers, and struggling to sit through a entire film. I am grieving simple joys—reading a magazine; playing a board game; hitting a swing-ball for hours—where now even split-screen TikToks, where two videos play at the same time, don’t satisfy our insatiable, miserable need to be entertained. I even have a sense of loss for experiencing tragic news––a moment in world history––without being drenched in endless opinions online. I am homesick for a time when something horrific happened in the world, and instead of immediately opening Twitter, people held each other. A time of more shared feeling, and less frantic analyzing. A time of being both disconnected but supremely connected.

I feel something similar when I talk about how America used to be a properly urban country, when I see these century-plus-old photos of bustling downtowns which are now freeway dead zones, streets full of people, trolleys running through the middle. This sense that we had something we didn’t know, but also this sense that it’s almost impossible to know that we’ll one day miss it.

Maybe it’s just grass is greener. Maybe it’s impossible to choose to forego something. Or as Katy Perry sang once, “I miss you more than I loved you.” There are these habits of mind that I run into that feel like looking at human fallenness. Things built into our human “operating system,” by sin or evolution or both, that we can discern yet can barely resist. The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.

Can we do anything about it? Maybe:

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can give future generations a real-world childhood. We can prioritize play. We can delay entry to social media platforms until at least 16. We can encourage young people to just hang out with each other, without supervision and without smartphones. We can take elements of childhood from previous eras and re-introduce them in modern life. But we have to remember what has been lost. When we are grieving record stores, mixtapes, old-school romance, and friends goofing around in ‘90s high schools, what are we actually grieving? Delayed gratification. Deeper connection. Play and fun. Risk and thrill. Life with less obsessive self-scrutiny. These are things we can reclaim—if we remember what they are worth and roll back the phone-based world that degraded them.

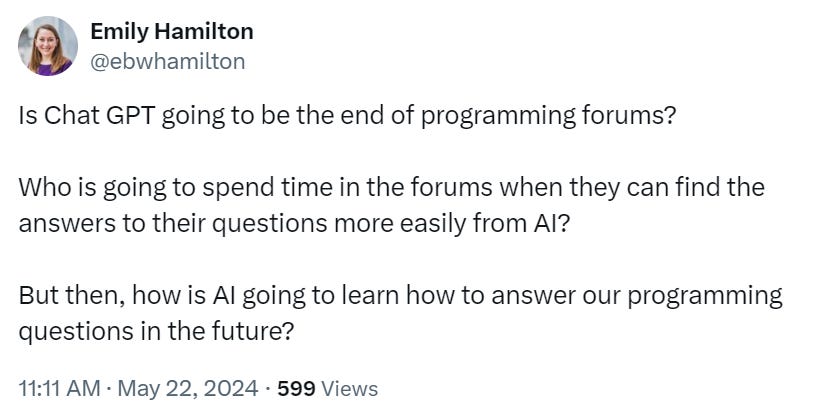

I just saw this tweet—literally as I was writing this piece—from Emily Hamilton, a housing scholar (though I’m the one who relates her tweet to anything to do with housing):

There’s something deep here, in that last question. Will this AI stuff and its subterfuge of “training” on human-generated “content” end up breaking the actual process of generation and innovation? Will it do to information—here’s my inevitable urbanism angle—what the advent of suburbia did to our traditional process of incrementally building up cities? An innovation too good to refuse, but which ultimately costs far more than we realize?

This all—the technology bit—seems to relate to this recent article in The Atlantic, on “cultural arbitrage”:

The most commonly cited disadvantage to this extraordinary societal change, and for good reason, is that disinformation and misinformation can use the same easy pathways to spread unchecked. But after three decades of living with the internet, it’s clear that there are other, more subtle losses that come with instant access to knowledge, and we’ve yet to wrestle—interpersonally and culturally—with the implications.

To draw from my own example, there was much respect to be gained in the 1980s from telling friends about video-game cheat codes, because this rare knowledge could be obtained only through deep gameplay, friendships with experienced gamers, or access to niche gaming publications. As economists say, this information was costly. Today, the entire body of Punch Out codes—and their contemporary equivalents—can be unearthed within seconds. Knowledge of a cheat code no longer represents entrée to an exclusive world—it’s simply the fruit of a basic web search.

The article is largely about taste-making and things like innovation in music, but it touches on this idea of the process itself—slow, inefficient, fickle—being key to the things that are eventually generated. Maybe in the long run it simply isn’t possible to take the work out of things.

This, in turn, makes me think of something else. I remember—pre-smartphone, pre-unlimited-data-plan—when you’d be chatting with a group of people and you could kind of propose a question or wonder something out loud, and everyone would submit a guess. It could be something as small as “What’s the capital of Alabama?” “Uh, Memphis?” “No, that’s Mississippi!” “No, that’s Tennessee!” “What is the capital of Alabama?” You could get some gentle comedy and teasing out of these things. And you might learn something.

Sometimes working through a question you can’t answer with someone, or the answer to which you know but don’t recall, is productive. It kind of forces you to stretch your brain, and it can help you connect with people. Now that you can just look these things up, a question is often not a conversation-starter but a conversation-ender: “I don’t know, look it up.”

The removal of these friction points ends up being isolating; it cuts out something in and of itself unnecessary, but necessary to the bigger things of forming relationships, sharing information, making something together.

What’s the proper analogy for this? Something potentially unpleasant, frictional, difficult to choose to do when it is optional—but integral to things we deeply need? It’s something like trying to get to a cooked dish without the heat and work of cooking. It’s not realizing that the result is necessarily embodied in the process.

Finally—one more link—I want to go back to something I wrote awhile ago, but which I think about a lot (I only wrote up what a presenter said, at an event):

A gas or electric fireplace is trendy, easy, and marketable. A real wood-burning fireplace is messy and requires more work (though I guess it’s also pretty salable.) But the thing about a real fireplace is that once you start the fire burning, you don’t know exactly when it will end, and you can’t turn it off. It creates a kind of pleasant, productive friction. “Let’s put on one more log.” “Oh, let’s just stay till the fire goes out.” That uncertainty is binding. It creates a setting for socializing that the gas fireplace doesn’t. “Alright, guess it’s time to wrap up,” you might say, as you flick the switch off.

There’s something subtly alienating, isolating, and anti-social about the smooth, frictionless operation of the thing. The good friction of the real fire draws people together in a way that is awkward to do entirely on your own, when circumstances are working against it.

Maybe the right analogy is trying to get to a fire without starting one.

I think of all of this as adjacent to urbanism, because cities and towns are a physical embodiment of the idea that people are inherently social, and that we need each other. Even more philosophically, urbanism is a reminder that we are physical creatures; that our needs and feelings and actions are mediated through the real world, and that digital technology is doing something metaphysically deceitful in concealing the physicality of the world.

The perseverance and resurgence of cities is evidence to me that we still know what we need, and that—our fallenness, again—the very difficulty sometimes of affirmatively choosing it is evidence that we need it.

Related Reading:

You Never Know How It Falls Apart

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,000 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

"it touches on this idea of the process itself—slow, inefficient, fickle—being key to the things"

Just as an aside - I think this is the joy of something like playing an instrument or learning a new sport or skill of hand - that a book can only take you so far, and you have to train your mind and muscles to it. That you start off bad, and there's usually an initial bar that's difficult to clear, and then there's rapid improvement, and then you hit a plateau...and decide on whether you want to keep improving or are ok with just being "intermediate." And if you decide not to cross the plateau to get back to skill acuiqisition (usually because of life intervening), you find that the hunger to do the things sometimes dissipates - the fun of it is the learning and getting better. Sure the destination of playing the instrument or surfing a wave is fun - but it's so much more fun when it's NOT automatic, when there's drama in whether you'll get there. It's riding the highs and lows of that experience that makes it worth it.

And typically, to really improve, it helps to have people around you who can help critique and improve your technique, trade tips, ensure your equipment is in good shape. A naturally developed community. I love reading - I read books as often as I can - but they tend to be a bit anti-social (as are personal screens) unless you join a book club. But a sport, even individual sports like biking, or running, or surfing and backpacking - almost invariably require being a part of a community. (Team sports definitely get tougher the older I get and the more other commitments of life intervene).

The New Yorker had a recent article that you'll be interested to read. It's sort of about these issues but also sort of orthogonal, in a very useful way.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/05/06/the-battle-for-attention