Last week, Shira Ovide, who writes a technology newsletter for the New York Times, briefly interviewed me for a piece she was writing about people who, for various reasons, like old tech. Guilty as charged. Here’s a little section of my clock radio collection, which I mentioned to her:

Here’s the bit about me:

Del Mastro said that he appreciates the creativity and craftsmanship that went into decades-old consumer electronics as well as the ability to understand how they worked.

“You can open up that spinning cassette player from 1970, and any layman can understand what is going on,” he told me. “It engages your brain and your hands. That experience is absent in a lot of modern technology or devices.”

I’d elaborate that final point this way: a lot of modern devices—anything from an Amazon Echo to a modern home theater receiver—is a literal and figurative black box. Literally, in terms of the sleek, minimalist design. And figuratively in the sense that most of the guts of modern devices are chips and software, not buttons, dials, knobs, and mechanisms. I do think there’s something kind of alienating about that. (Although maybe only if you think about it!)

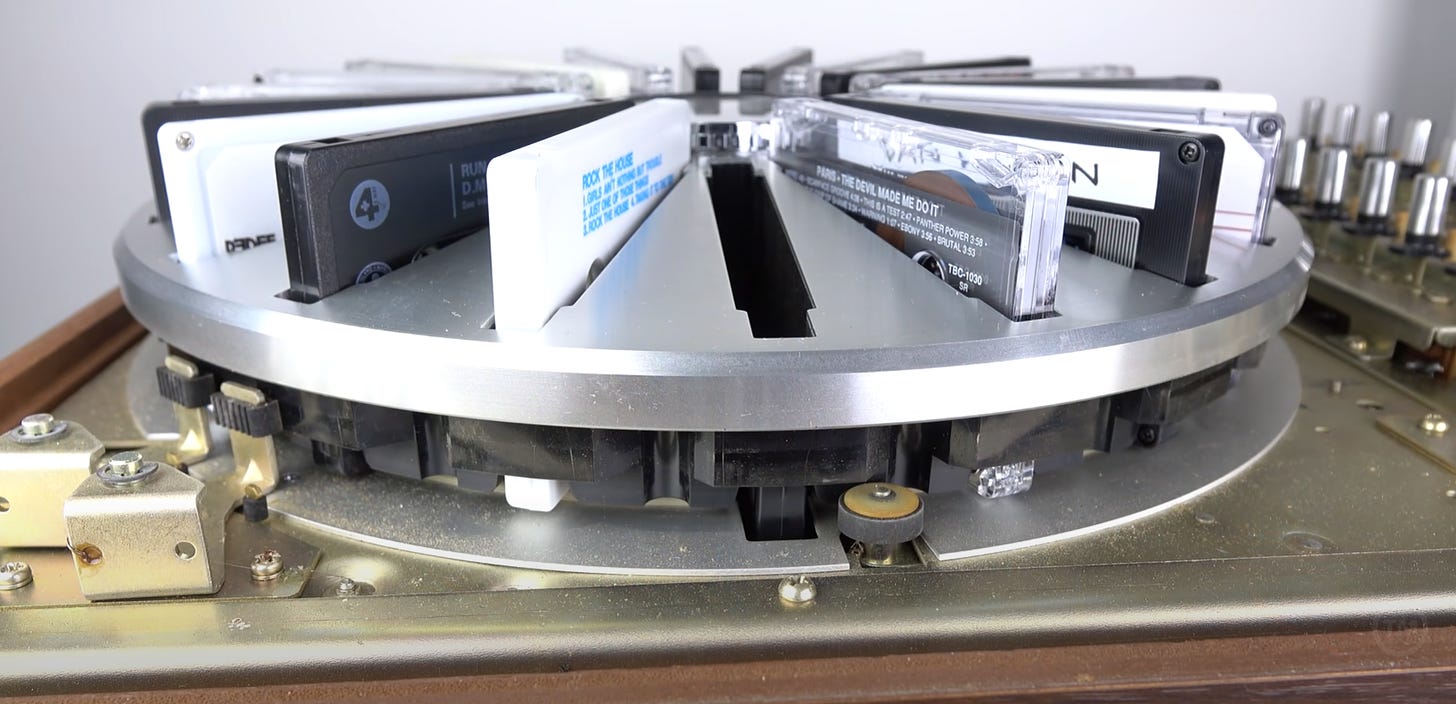

The device that I called a “spinning cassette player” was this Panasonic carousel cassette changer—i.e., able to play a large number of tapes in sequence automatically. I wrote about it after watching this cool demonstration video by Techmoan, a British YouTuber who features all sorts of old and often forgotten technology on his channel.

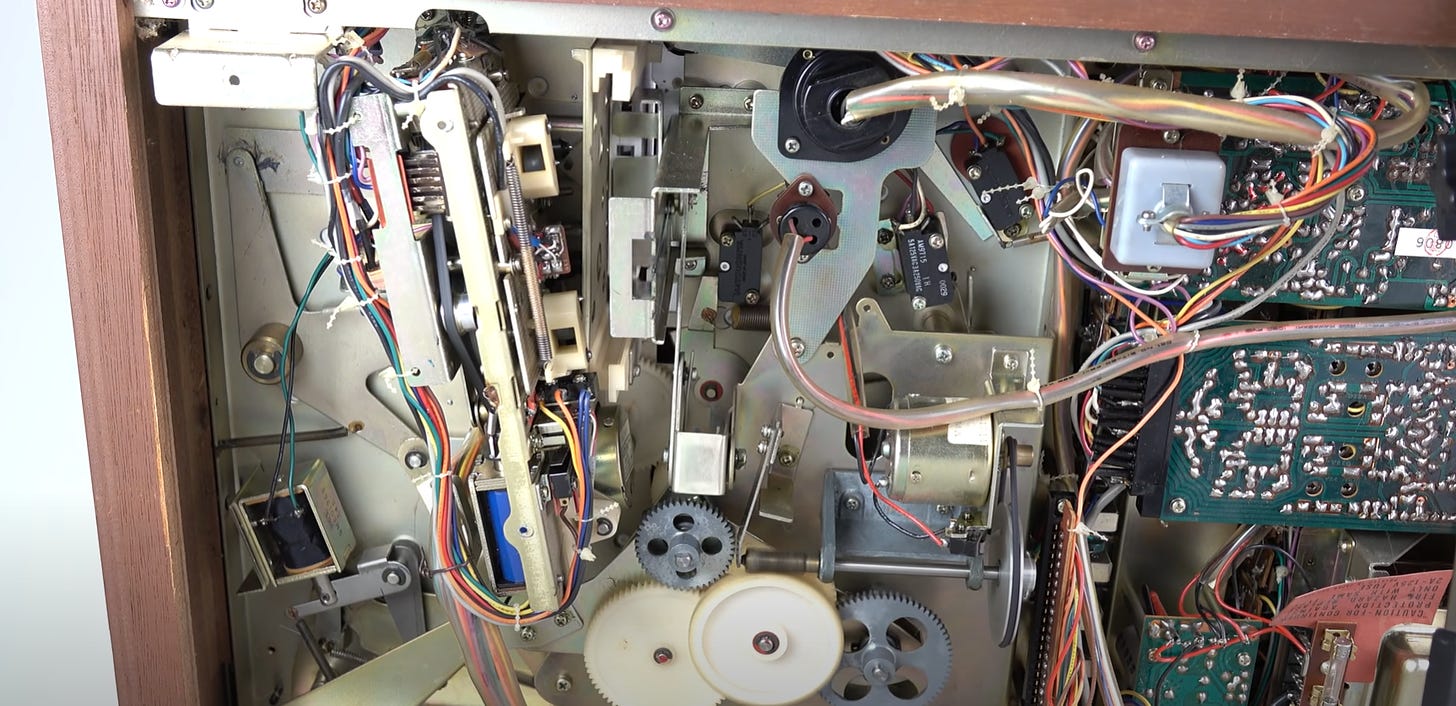

Here are a couple of screenshots showing the mechanisms inside, but the whole video is very cool and worth watching, if this at all interests you.

The quality and the complexity of the craftsmanship in devices like this is just astonishing. None of this, or very little, is digital. Everything about it is physical, and engineers and designers had to imagine, prototype, manufacture, assemble, and fine-tune this incredibly complicated mechanism to make 20 cassette tapes in a row play seamlessly.

Not for nothing, I once compared watching one of these things in action to attending Mass, as a Catholic—the interplay of concept and physicality, the tactile, almost ritual element of using a device like this—there’s something similar going on. St. Augustine defined a sacrament as “the visible form of an invisible grace.” If you generalize that idea, I think something like it applies here.

But beyond that—and beyond pure nostalgia or curiosity—I think something else explains the resurgence of analog technologies. And with vinyl sales increasing ever year for almost 15 years now, and other indicators of interest in more physical technologies popping up, I think it’s safe to say this phenomenon is more than a fad or an aesthetic. (This article is from 2015, and the trendline has only gone up.)

One thing that pops up, whether in articles about vinyl records, or against streaming television or music, or similar things, is that increasingly people welcome a little bit of friction and inconvenience. In fact, seemingly infinite choice, available instantly, is its own kind of inconvenience. Many feel that it makes us more passive, and blunts our ability to concentrate deeply. Having to actually do something to make the movie or the song play focuses your mind and makes you invest a little bit in the thing you’re consuming. (Not to mention issues of ownership and privacy.)

It’s interesting, because I doubt anyone really thought about this back when all technology was analog. Did anybody write such philosophical appreciations about cassette tapes in 1975? Maybe, but most commentary probably looked forward to the next innovation. So it’s interesting that the mere passage of time changes how we perceive these things, and even what effect they might have on us psychologically.

If there are other old-tech enthusiasts here, I’d love your thoughts on some or all of this.

Since a bunch of you came in after seeing me linked in that NYT piece, I wanted to share some of my other old-tech writing here as well, both here and at other magazines. While my primary topic is urbanism and land use (you can view some of my favorites in this 2021 end-of-year post), I do come back to this cluster of issues fairly often. Some links and brief descriptions below:

“The Last Cassette Player Standing.” I wrote here about the cassette players being made today—yes, they are still made—which are virtually all based on a single mechanism produced in China, which turns out to be an unauthorized clone of a low-cost Japanese mechanism from the 1980s. (The “mechanism” refers to the physical and electronic parts that run and play the tape.) Basically, without low-cost Chinese manufacturers cloning this old Japanese design, there might not be any cassette players still being made anywhere, at all.

“A Repair Journey Through Low-Cost Manufacturing.” I had a problem with my little inexpensive single-room dehumidifier, which led me to opening it up, working on it, and learning something really interesting about the low-cost manufacturing ecosystem in southern China.

“The Curious Case of the Last Record Changer.” I guess I find lasts interesting. Here, I took a look at the provenance of a 1990s Crosley record changer, which turns out to be a virtually exact clone of an older British design that was licensed by a Taiwanese company in the 1980s. Some people even think the Crosley units were assembled with new-old-stock parts, and that they were discontinued when those parts ran out. That’s impossible to verify, but it’s very interesting how a company-specific design can end up entering a sort of public domain.

“The Record-Tape Missing Link.” Thanks again to Techmoan, I learned about a German audio format that used tape cartridges, but the tape was a thin spool of vinyl—basically a linear record. It had some issues, but I wonder if there’s an alternate world in which that idea was refined to the point where it won the later format wars, and where records and magnetic tape ended up being footnotes in audio format history.

“The Phylogeny of the Watch.” Here, with some more reference to 1970s home stereo equipment, I talk about how manufacturing and technology looks more like evolution than creation.

“When American Record Companies Hated Japan.” One reason I find this stuff so interesting is that it’s an entry point into all sorts of political, economic, cultural, and commercial history. Here, a late-1980s dispute between Sony and the American record industry gives you an idea of the trade landscape between Japan and the U.S. at the height of the Japan-panic era.

A final little piece of funny internet weirdness. Every once in awhile, something I write will end up duplicated at dodgy websites, often in broken, machine-translated English (even though they’re originally written in Enough.) It’s a kind of spam known as “spamdexing.”

This time, Shira Ovide’s NYT piece ended up widely “spamdexed,” with some funny results, like these:

“Citizen,” “cassette participant,” etc.

But this one takes the cake:

I often write about walkability, pedestrian safety, and related issues, so this headline sounds like something I would write. But it ended up that way because whatever translation software they ran this through rendered “Walkman” as “pedestrian”! The internet is very, very weird.

Related Reading:

Waking Up to the Joy of Clock Radios

Fry’s and the Self-Made Computer

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive of nearly 300 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

I think "friction" is such a good metaphor for having a bit of resistance in our interactions with technology, because it captures a lot of the nuance around the issue. In physical life, we tend to think of friction as bad, but if you stop and examine it it's really only an issue when it's unexpected or otherwise "incorrect" friction: two gears grinding against each other because one is out of alignment, etc. But much of what we do *requires* friction to work at all, it's just generally seamless because it's all been carefully designed to put the friction where it's needed and to keep everything else smooth.

I guess the one place where the metaphor does kind of break down is that in the physical world, the understanding of friction is the domain of the engineer and physicist: there's pretty much a "correct" level of friction that our brake pads need for the car to be safe and effective to operate. But for human interaction with digital technology, it's a much more personal decision, and that's kind of the problem with a lot of mass social technologies. Their incentive is to drive "engagement" based on mass aggregate metrics, which ends up purging almost any source of friction, even ones that most users would want. This leads to many people having to self-impose their friction in order to have a healthier interaction with the system, but this can be tough to maintain. I try to abide by Alan Jacobs' "Take a 5 minute walk before responding" rule, but man if it isn't hard not to just snap a quick tweet back before walking away....