I was in The Bulwark the other week with a review of Henry Grabar’s excellent book Paved Paradise, on parking policy and how parking explains a great deal of the American built environment, mostly for ill.

This was a fun chance to elaborate a few points I’ve been making in this newsletter. Grabar is easy to read, and entertaining, but full of real information, examples, and data, and it really fits with a lot of what I’ve been thinking and observing lately.

I don’t softball the opening here:

Just about every urban parking lot once housed a building. Unpack that one curious fact and you can learn a lot about how the logic of cars as the default mode of transportation is inherently at odds with the logic of cities as dense, vibrant, bustling places.

I don’t think this is an ideological statement. I believe it is simply true, as an observational matter. It comes down to the sheer amount of space needed to move and park cars which ultimately have relatively few people inside of them. But there’s a dynamic element to this too: parking doesn’t “absorb” a fixed number of cars which are simply there; we drive because we can park, and more parking generates more driving:

“By making parking spots as obligatory as bathrooms, the city . . . forced housing to bear the costs of driving,” Grabar writes. Fine, you might think—but where will everyone park otherwise? The answer to that question involves a deeply conservative insight into the dynamic nature of human behavior, which will always ultimately thwart the expertise of engineers, social and traffic alike.

We drive, in large part, because we can park. ‘Where will everyone park in a parking-free building?’ is the wrong question. “Precisely because they offer access to places where car ownership is optional, buildings without sufficient parking are among the most in-demand structures we have,” Grabar writes. Just as traffic engineers have concluded that it is impossible to highway-build your way out of highway congestion, city planners in the twentieth century learned that it is impossible to parking-build your way out of urban street congestion. Highway capacity begets driving; easy parking begets driving. If you build it, they will drive.

That’s the sort of high-level analysis. What Grabar does very well is illustrate what, specifically, on the ground, this all means. Here’s my bit on that, dealing with three questions which he covers. Why is modern development scaled so large? Why do classic urban buildings often decay or sit derelict? And why do vibrant cities often have unbuilt lots?

Why is the scale of so much modern residential development so massive, leading to not-unreasonable complaints that new buildings will dwarf their existing surroundings? “Parking requirements helped trigger an extinction-level event for bite-sized, infill apartment buildings like row houses, brownstones, and triple-deckers; the production of buildings with two to four units fell more than 90 percent between 1970 and 2021,” Grabar finds. Instead, the kinds of apartments that did get built were those “whose design was dictated by parking placement,” such as the so-called “Texas donut” design in which a ring of apartments circle a parking structure. Grabar offers up an apt metaphor: “Parking,” he writes, “is a mutant strain of yeast in the dough of architecture.”

Why do so many cute classic buildings on old Main Streets sit derelict or disused? Because a renovation entailing an alteration of a building’s use can activate codes that the existing structure/business were exempt from for having antedated them: The dingy old auto shop was grandfathered into an exemption from the current parking code, but a café taking its place would be held to the requirements. This forces enterprising small developers and business owners to come up with new parking as part of their proposed renovations, which raises a frequently insurmountable obstacle: The new parking cannot be found without demolishing another nearby structure, or by incurring a cost that might threaten the plan’s forecasted profitability.

Finally, why are there so many vacant lots even in economically healthy cities? Grabar tells us that Los Angeles is full of unbuildable lots because the parking requirements are impossible to meet, financially or in terms of space, something that is true for most American cities overall. Parking requirements have rendered existing traditional cities unusable as raw material for development rather than only as blank slates; they’ve broken the continuity of the physical and geographical history of these places, disregarded the reasons for how and why they were built in the first place. A radically different pattern is now required, one that is at odds with these places as they exist. “Los Angeles banned itself,” says a tour guide in old downtown LA.

In other words, parking. Parking forces out small-scale enterprise. Think about how small some old storefronts are. Hardly bigger than an automobile. Look at this restaurant I wrote about the other day, for example. It’s hardly more than a trailer. The sidewalk that surrounds it is almost as big! No parking, of course.

But you typically can’t do that anymore, even in many cities which now have a parking ordinance at odds with the actual place as it exists. (Well, you can, but you need to go through the excruciating bureaucratic process of getting a variance/exemption, which means making a case to the board, undergoing public input, etc.) Only the chains and corporate companies can afford to open stores where parking takes up a much larger amount of land than the actual business.

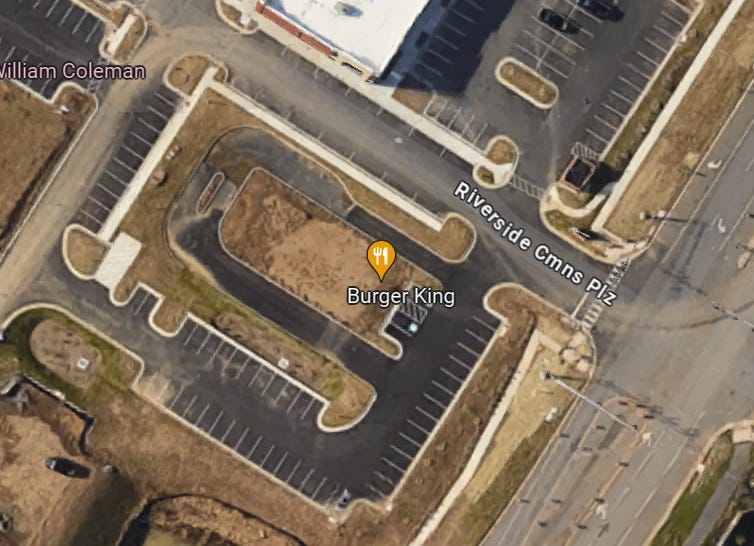

Look at this new shopping center in Ashburn, Virginia. The Burger King will be in the little island in the middle of the drive-thru loop. Compare the lot size to the structure size:

Parking—and by extension, the car as the default mode of transportation—sets the minimum cost of doing business above the level of the individual. It forces the scale of commerce “up,” towards more size physically, more concentration financially, and more distance geographically. We think of the car as an engine of opportunity, permitting someone to easily move across the country or access jobs relatively far away. But the effects of the car on housing, land use, and entrepreneurship reduce the value of that mobility.

The car cannot be used as a “cheat” or a “hack,” because the car itself alters the landscape which it would help you navigate. Using the car to access opportunity ends up being a little bit like printing more money to buy more stuff. And the inflation that money-printing causes manifests itself, in the case of cars and the built environment, as this “embiggening” of scale.

Again, this is a deep insight of the philosophical conservative variety, and this, to me, is the real problem with cars.

So in this vein, I take Grabar’s argument further, in a way that he sort of hints at, and take it in a metaphysical direction. We have to think in a deep way about what cities are.

There is clearly a set of deeper, almost metaphysical issues. Consider the moral implications of the conflation of cars with people; the subtext that people who manage to get around without a car are loafers or cheaters; the idea that urban amenities like walkability to shopping and dining are prizes to be earned and not essential components of normal neighborhoods.

The ultimate insight to which Paved Paradise points is that our parking policy, our highway policy, and our transportation system fundamentally aim to do something that grinds against basic human realities. Hiding behind the arcane parking minimum, the underpriced curb in the unaffordable city, the reams of byzantine regulations, and so forth is something that amounts to a sort of revolutionary ideology.

The difficulty with the question Where will I park? isn’t that it is trivial, but that answering it requires relearning a lost conception of what, precisely, a city is.

These are the highlights, but read the whole thing! And I have a lot of notes I didn’t get to use in the initial review, so I’ll probably do a “second review” type piece here in the coming weeks.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

I knew this was your headline without seeing who wrote it

Nice perspective getting to the standard bottom lines:

street parking should not be free.

parking should never be mandated

parking fees might (?) act as pseudo road use and congestion charges in certain places