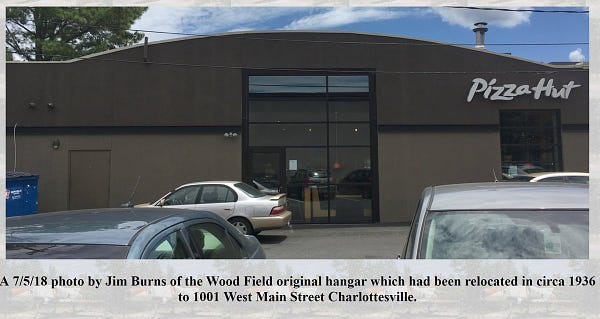

We’re in downtown Charlottesville, Virginia today, and I promise this building’s connection to Pizza Hut is not important and entirely coincidental to its history.

This is Google Maps’ most recent Street View imagery; in fact, the Pizza Hut is not in business any more. But this is a little odd-looking for a small strip plaza, isn’t it? What would your guess be as to how it began life?

I would have two, seeing it for the first time: a bowling alley, or some kind of auto garage.

Neither of those would be correct—despite this phase of its history. (Notice the Pizza Hut retains the left-most garage door window space and the big one on the building’s left wall!)

It turns out this building was not quite built on the lot it occupies. It was moved here in the mid-1930s. Or at least I thought it was, because a few Charlottesville-area folks on Twitter said so. But they also found this article about the opening of the Pizza Hut by area journalist Sean Tubbs, who wrote of the structure:

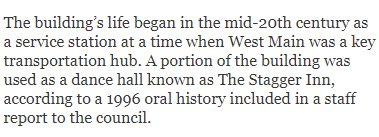

The building’s life began in the mid-20th century as a service station at a time when West Main was a key transportation hub. A portion of the building was used as a dance hall known as The Stagger Inn, according to a 1996 oral history included in a staff report to the council.

Well, that’s a bummer. So it only looks like it wasn’t originally designed as what it is?

But wait. The official Charlottesville property record database identifies the structure as having been built in 1920. (And also as having additions of a first floor and basement in unidentified years. Wasn’t it always a first floor—or does that mean an additional single-story expansion? Aspects of these records can be unintelligible to a layman.)

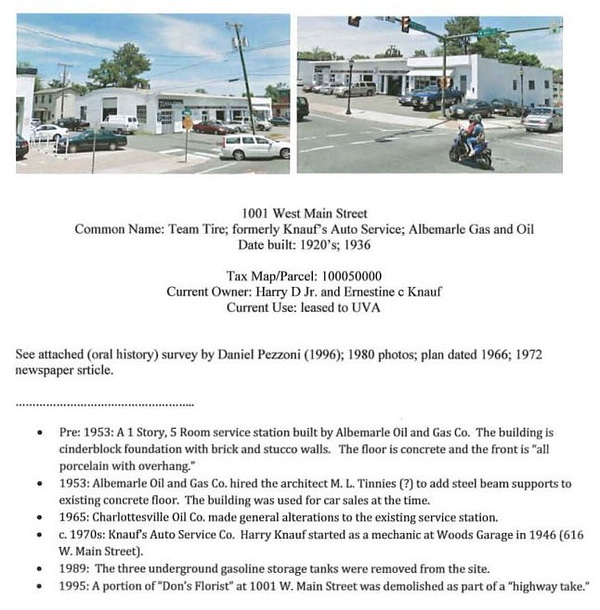

But wait. Here’s a 2013 document from the Charlottesville city government, produced during the process of determining whether or not this structure is historic. It includes information from a 1996 oral history, which offers conflicting information on the build date:

So it looks like something happened in 1920, and something happened in 1936. (Aerial imagery only goes back to the 1960s, and is too grainy to really tell anything. It does appear to confirm that the arched-roof structure has been there as far back as the imagery goes.)

Here are a couple more images of the building. First, here it is under construction/renovation from street level:

And here’s the right half being re-roofed, and a good view of the older, left half from the air:

Now if you haven’t guessed yet, the truth is that this building has something to do with an airplane hangar from an old Charlottesville-area airport!

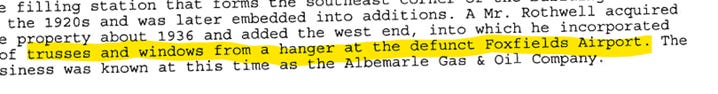

The question then revolved around whether it’s an entire hangar that was moved to the site, or whether it’s a hodgepodge building that includes parts of the hangar. Despite a couple of people saying it was moved, I think that’s a simplification; that 2013 city report includes this description, which seems too bizarre and detailed to be wrong:

This composite building consists of three sections. The earliest section, of indeterminate age, is the building’s two-story northeast corner, and is of heavy frame and brick construction with a modern concrete-block and metal panel facing. The building’s southeast corner was added as a service station, and it features aluminum-framed display windows and an awning. The west end is constructed of brick veneer over terra-cotta block and incorporates large industrial windows and a bowstring-truss roof from a former airplane hanger. This wing has several garage door bays and is faced with enameled metal panels.

You can see the enamel panels and, of course, the garage doors, in the image showing the building in its auto shop days. And of course you can see the hangar-style roof. As noted, the window/bay placements survived the renovation into a Pizza Hut.

A website that documents old airfields repeats this version of the history, and also includes some cool pictures if you scroll through, including of the interior with the arched roof exposed.

I was not positive about the moved/used-the-roof distinction, however. A fellow on Twitter suggested that Jeff Werner, a planner who works on historic preservation issues for the city, might be able to confirm this detail. I reached out to him and he emailed me back. He attached some old property maps which fit with the history I had landed on (no pun intended), and which suggest that anything from before 1936 is drastically altered. He also attached a clip from a different city document that agrees. (The maps also show that in the 1800s, the lot was occupied by a sawmill, of all things!)

And the Foxfields Airport? It turns out it’s now the Foxfields horse-racing track! There’s no trace of the airport left on that piece of land—except another hangar that was left standing, and which looks just like the small strip plaza from the air.

So the earliest part of the building seems to still exist in some fashion, having been swallowed up into the newer parts. And 1936 is the year that a major addition was constructed using the roof and windows from the hangar. With that much of the hangar moved over, perhaps simplifying it into “the hangar was moved” makes it clearer. But this series being what it is, I like to know the full details. And there they are.

Here’s a piece of one of a couple of Twitter threads on the history of this building. It includes a photo from the defunct airfields website—whose caption, unlike the piece of text that quotes the 2013 document—identifies the structure as a relocated hangar. The thread also includes a screenshot from a different part of the 2013 document which skips the hangar bit and identifies the building as having been majorly expanded in the 1950s.

If this is confusing, that’s the point.

After last week’s Didn’t Used to Be a Pizza Hut deep dive, a few people suggested that county offices or public libraries would have all of this sort of information—not just property records, but phone books, county directories, local newspaper archives, etc. Maybe tracking down the details of 20th century commercial properties wasn’t as difficult as I made it look. In some cases, these resources do exist, and in many cases this level of detective work is not required.

But there’s no way all of these various sources of information have been preserved for every year that they were produced, and in many cases they won’t be digitized and/or searchable. Heck, the city of Charlottesville itself, in 2013, ended up two different accounts of the history of this building. Official records are sometimes mistaken, or fail to capture relevant information in unusual cases like this. Sometimes the full history of a property is only revealed by multiple types of records.

For me, and hopefully for you, this is fun. But for historians who take America’s 20th century built landscape seriously, it points to real issues of record keeping, and reveals a surprising level of obscurity for artifacts of such recent vintage.

It’s also interesting how buildings were so often assembled and revised in those days, rather than simply torn down and rebuilt. This speaks, perhaps, to higher costs and less standardization in construction, but also to a canny resourcefulness and creativity that we’ve perhaps lost in some ways.

By the way, I’m including more related reading links today, which I think are some of the more unique buildings I’ve featured in this series. You may have already seen them, but check them out!

Related Reading:

What Do You Think You’re Looking At? #3

What Do You Think You’re Looking At? #6

What Do You Think You’re Looking At? #8

What Do You Think You’re Looking At? #28

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive of nearly 300 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

This is a great article that does put a lot of things together. It also made me look up the cvillepedia page for this building and I'll use this to update it. Being wrong is sometimes part of the job when you're writing stuff on deadline all of the time. But, this is great and a nice treat to see this morning.