Over the years, I’ve written a number of pieces on the culture and economics of Christmas in America. (Probably my favorite, from three years ago, was a piece thinking about how as the age of marriage has risen and divorce has become more common, we’ve seen “complicated” Christmas songs that are perhaps more true to life than the simple old classics.)

I’ve always found it interesting how some of those old Christmas songs reflect, to put it tritely, simpler times, whether or not those times existed exactly as depicted. (Yes, I know Dolly Parton did “Hard Candy Christmas,” but I’m talking about the stuff on the radio stations and online playlists and store PAs.)

I also find it interesting that there are reminders in their lyrics of the now-outmoded ways in which many of us celebrate: Christmas dinner used to be a Thanksgiving redux, for example—turkey and pumpkin pie. Again? A hammer and a toy whip used to be “a glorious fill” for a stocking (and nothing in “Up on the Housetop” suggests that the stocking was a mere prelude to the stash under the tree).

Anyway, this year for my Christmas piece, I was in The Bulwark looking through Google’s Life Magazine archive, and playing with a fun question: how early did Christmas “begin” in the middle of the 20th century? Do these old magazines suggest that Christmas has become increasingly commercialized, or has it been more or less the same on that count for as long as the magazine archives exist? (Starting in the mid-1930s and ending in the 1970s).

Like all such questions, there might not be a watertight answer. It’s funny how multiple, seemingly contradictory trends can be ongoing at the same time. For example, America had already begun to deindustrialize by the time rural electrification was fully complete. Or another one—I think the case can be made that traditional small towns did not completely stop getting built until the 1950s, yet around that same time, Disney was already in a sense memorializing or looking back at that pattern with its “Main Street, USA.” The last instance of a thing often comes long after the thing has lost cultural currency writ large, and in that sense different periods can overlap.

Anyway, that’s a bit of a tangent, the point being basically this:

There’s something a bit strange about the consumerism of this period—but maybe it just looks that way from so many years in the future. The plainness and simplicity of many of the gifts—pens, clothes, countertop appliances, televisions and radios, electric shavers, fine whiskeys—seem at odds with the compositional intensity of the advertising. Quaintness and radicalism here go hand in hand.

But maybe “quaintness” is just a filter we lay over the past. What may have seemed extravagant in one era can seem pleasantly plain and old-fashioned in another. The color stereo TVs and the solid-state electronics were real innovations in their time. The past did not seem old-fashioned to those who lived it. One day, a smartphone may seem similarly quaint, a curious little reminder of the simplicity of life in earlier days.

Is Christmas more or less commercialized today? It’s hard to say. On the one hand, the big-box stores sometimes begin stocking Christmas merchandise as early as late August. On the other hand, explicitly Christmas-themed print-magazine ads in October, before Halloween, do feel like a bit much, even today.

Narratives always involve simplification, and it’s also possible to overinterpret bits and pieces of popular culture.

Yes—the October 21, 1966 issue of Life featured a Christmas ad, for a Christmas music record box set. That’s earlier than 20 or 30 years previous, but as early as the 1930s there were Christmas ads in print before Thanksgiving.

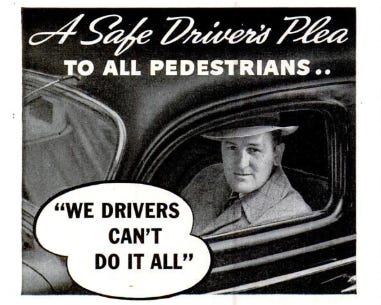

There’s also so much other cultural information in these magazines. There’s a ton of tobacco advertising, for example. There are a lot of gee-whiz ads for stuff that’s extremely common today: electric heaters, kitchen appliances, things like that. There are tons of car ads, and a lot of columns aimed at motorists. There’s even this one, semi-blaming pedestrians for traffic fatalities:

You can see how this time was very transitional, very much both radical and traditional, as I put it above. I ended my piece with this: “Paging through these digitized old issues of Life is a fascinating exercise, and a window into a country that was very nearly, but not quite, our own.”

That way of describing the receding, almost-recent past is something a guest writer from the early days of this newsletter first wrote, and I’ve always loved it. He wrote, in a piece about driving a station wagon:

The interesting thing about driving a car from 30 years ago built to plans from 50 years ago is that you’re inhabiting the very different assumptions made by a culture very similar to yours….The nice thing about driving it is everyone wants to talk about it….The bad thing about driving it is that you’re constantly reminded that you’re richer than the people who bought your car, in ways that have changed what you value.

This kind of encapsulates why I find old consumer products and bits of popular culture so interesting, and to this day that little passage is one of my favorite things I’ve published.

Check out the whole Christmas piece, and go do some exploring in the Google Life archive! I’ll probably come back to this “thoughts on old magazine ads and columns” thing too, so stay tuned!

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

I've always just assumed things have gotten more commercialized, maybe because it felt like Christmas was becoming more secular (but is that even true...). I will say, it feels like Christmas gift-giving has exposed the heightened consumerism of the rest of the year. When my mom was a kid, Christmas was the only time they get presents; those would be the toys or tools they played with or used (and shared) for the rest of the year. Fast-forward to our current extended family practice, and I'm just holding off on buying a narrow category of goods - things I want but don't need - for a mere two pre-Christmas months to give my Secret Santa something to buy. We're effectively giving up impulse purchases for Advent.

The October Christmas ad is cool to see. During the annual tradition of everyone talking about how early Christmas products are appearing in stores this year and how it gets earlier every year, I've always wondered if that's actually the case or if, after a whole year, we just forget how early it does all start. This example makes me feel more confident it's the latter!