The Last Town In America

When was the last time we unselfconsciously built traditional urbanism?

Readers: For just this week, until and including the Sunday before Christmas (December 22), I’m offering a holiday discount for new yearly subscribers! If you’ve been on the fence about upgrading to a paid subscription, this is a great time. Your support—whether reading, sharing, or subscribing—keeps this thing going. Here’s to a fifth year of The Deleted Scenes!

The last official release for the iconic Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, was Wario’s Woods, which hit the North American market on December 10, 1994. This was not only years after the release of the NES’s successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, but precisely a week after the Japanese release of the Sony PlayStation, which hit Japanese stores on December 3, 1994. Wario’s Woods was released before the PlayStation in Japan, but it’s quite remarkable that an official NES game came out two video-game console generations later. (A Europe-only NES Lion King video game even came out in 1995!)

The “last” of a thing is often only notable looking backwards; Wario’s Woods was a puzzle game. It wasn’t an adventure game, RPG, or platformer, the genres that made up most of the period’s hit games. There was no intentional go-out-with-a-bang final release to see off the NES. It was not, at that time, beloved, just obsolete. There were probably many stores by that time which barely even carried NES titles anymore. Wario’s Woods was essentially a perfunctory release to eke out a last bit of revenue. Essentially, an accidental last. Even the question of “the last NES game” only became interesting later.

Which brings us to New Town, North Dakota.

The U.S. federal government located and platted the town in 1950. It was a designated replacement for several small settlements that were to be flooded for a dam project.

Other than being two-thirds Native American, New Town is not particularly notable. It is not large, or unique, or likely to be interesting in any obvious way to a passerby. It’s a typical American West small town, with a Main Street that accommodates cars more than a classic eastern small town, and a wavy street grid that took some design cues from the quasi-grids of suburban developments which were exploding in popularity in the postwar years.

The only thing that is truly notable about New Town, North Dakota is that it is, possibly, the very last place that could be considered a traditional town that was ever unselfconsciously built in the United States.

This question—when was the last time America unselfconsciously built a traditional town—may not be precisely answerable. You need to pin down your definitions, and your parameters.

“Unselfconsciously” rules out the “New Towns”—a movement name, not a place name—of the 1960s, which included Reston, Virginia; Columbia, Maryland; and Irvine, California. It also rules out the 1980s New Urbanist developments like Seaside, Florida or Kentlands in Gaithersburg, Maryland, which very consciously sought to imitate the then-lost art of traditional urban development.

Perhaps those exclusions don’t make sense, but I think they limit the question in an interesting way. You could phrase the question differently: at which exact point can you say that the obvious break with the past in building and placemaking that happened in the 20th century actually happened?

You also have to define what, precisely, a “traditional” town is. This is not a cut-and-dry question. It’s a little bit like asking whether, or why, the archaeopteryx is “really” a bird. It’s a question of a critical mass of old or new features. Those might include: attached structures on Main Street (or throughout town); multistory or mixed-use structures on Main Street (or throughout town); a grid rather than a hierarchical road system; at least some apparent or intended walkability; elements that suggest predominant car use, like buildings set back behind parking lots; and other things that we typically understand as old-fashioned or modern planning features.

Of course, many towns were not “built” all at once (though some rail towns went up so quickly that you could describe them as having been built at a specific time), and there are places from the early 20th century which once resembled classic towns and, over time, came to resemble suburban commercial strips. It’s possible, in other words, that “the last town ever built” no longer exists in recognizable form, making the question functionally impossible to answer, or requiring the addendum “that still exists more or less as first constructed.”

The question would also exclude some obviously suburban places that were built in a similar manner to old towns—traditional plats sold to developers, with minimal rules as to what had to go there. Some folks suggested Coral Gables, Florida as an example of this. And again, some places that arose in this manner will today appear far more typically suburban than they might have in their initial iteration.

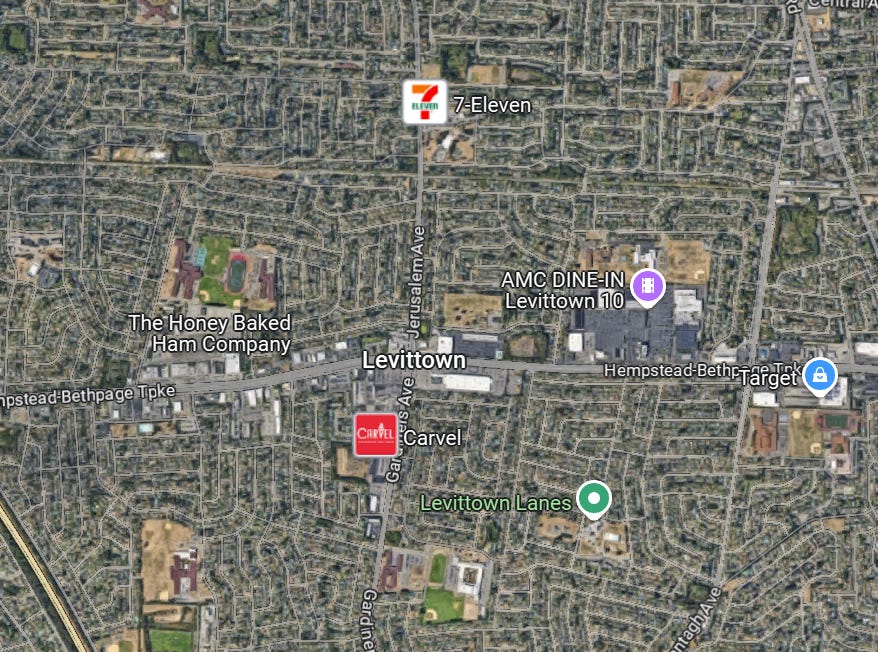

One more question here would be this: by today’s definitions, does an early development like Levittown “count” as a “town” rather than a “suburb”? Levittown’s basic form remains quite unchanged from the earliest aerial imagery I could easily find, which is from the 1960s (and it wouldn’t have changed much from its construction to that point).

Levittown’s street network is sort of recognizable as an altered grid, rather than a completely modern hierarchical road structure. It retains the placement of schools and churches within neighborhoods. It did, however, have separation of commerce from residential, though many small towns effectively also had that before zoning or planning ideas demanded it.

Levittown had a fully modern big-box store and a couple of strip plazas, but its largest shopping center resembled an actual urban street. That shopping center still had both a front and a back parking lot, suggesting that while walkability appears possible, it was not for the most part intended.

This image is actually taken from the shopping center’s front parking lot, which is effectively a street! The Levittown builders transposed an urban commercial block, complete with its street, into a commercial parcel along a main suburban road. This is a very early iteration of the strip-plaza form. But to me, it still counts as definitively not a Main Street.

What looks like the “street” here is a parking lot with a traffic lane running through the middle, and what looks like a street-facing block of businesses is the strip plaza. Off to the left is the actual road. Note that the parking is diagonal, just like on an urban street that has been expanded to accommodate cars. In other words, at the time Levittown was built, there was not a definitive suburban/car-oriented design language, as it were.

If Levittown is, or is nearly, the “first” “true” “suburb,” then the “last” “true” “town” must be from around the same time, with just enough in its mix of new and old features to classify it as a town and not a suburban development.

Levittown was constructed by a single master builder between 1947 and 1951, and New Town was platted in 1950 and sold and mostly built by 1953. New Town, being founded by the federal government, may have simply gone for the simplest known way to build a town, rather than experiment with the suburban planning ideas of the time. In other words, because the government was involved, the town may have ended up more old-fashioned than a settlement being built in the 1950s otherwise would have.

I showed you Levittown’s almost-Main Street. Here is New Town’s barely-Main Street. It’s in the middle of this aerial:

And on the ground:

Like Levittown’s shopping center, New Town’s Main Street has ample parking off the main roadway. Unlike Levittown, however, there’s a true downtown commercial district rather than several separated shopping centers. And unlike Levittown, the parking lot lanes here run the full length of the commercial strip, making them not quite parking lots but…parking streets. Like Levittown, the commercial structures here are mostly one-story and don’t appear to have any walk-up apartments or other sundry uses mixed in with commerce. Unlike Levittown, there are attached but separate structures here.

In other words, this is essentially the very last iteration of Main Street before the idea of “a commercial area surrounded by residential areas” was simply no longer something recognizable as a Main Street at all.

Here, from Google Maps, is the entirely of New Town:

Churches and schools are mixed in with the neighborhoods. It does not look like New Town included multifamily structures initially—with a lot of land and few people, that may have been simply because they were unnecessary and not because planning orthodoxy proscribed them. (The duplexes and apartment buildings towards the top right of the satellite view were built in the 2010s; oddly, the duplexes appear outside city limits, but connect to the town’s streets.)

I can’t say that this is definitely “the last town in America.” But it looks very much as one would expect such a place to look, and it comes from the time you would expect to see a last appearance of such a form.

The old way of building towns more or less faded away without much fanfare. Whatever understanding there was at the time that we were embarking on a revolutionary and untested manner of building human settlements never became a mainstream impression. Even the New Towns of the 1960s were experimental, and did not resemble traditional small towns or urban neighborhoods, even though they attempted to embody many of their features.

It was probably not until the New Urbanists, or even later, that any real number of Americans began to think in terms of the question “Why did we stop building actual towns and cities?” Due to urban renewal, even many of our old cities lost their history and their classic urban character.

It is remarkable, almost mystifying, how quickly we forgot a thing we had done for all of our history. But perhaps it’s also remarkable how briefly the new suburban orthodoxy reigned as the standard, default option. Between New Town and the first New Urbanist project of Seaside were only 30 years.

That, perhaps, is the point of identifying that “last” town: it suggests that, on a certain timescale, we hardly ever abandoned traditional urbanism at all.

Social card image credit Flickr/Andrew Filer, CC BY-SA 2.0

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter, discounted just this week! You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

In recent decades, there has arisen a conscious urbanism that seeks to make intentional decisions about what new towns will look like.

Before conscious urbanism, the placement and shapes of towns were 100 percent dictated by the available forms of transportation.

London and Paris are located at the first place that a major river can be crossed by the bridging techniques available at that time. Before 1840 towns were almost always located at the junction between roads or between a road and a river. These towns took on a roughly circular shape because that was best adapted for foot transportation within the town.

When steam railroads came in, they had to take on water and fuel (wood or coal) very frequently. Hence the phenomenon of railroad towns, which tended to be grid-shaped, because of the influence of enlightenment thought as well as a compact shape fairly well adapted to foot transportation.

Dwight D Eisenhower pushed the Interstate bill through Congress and so became the true father of suburbia. Now, in the densely populated portions of America, the true Main Street is the local interstate, and suburbs and commercial areas are blobs huddling close to interstate exits. While 1930s designers may have thought up the suburban pattern, the interstate system made it the most efficient use of automobile transportation. Since you needed a car to travel the interstate Main Street, you also needed a car to navigate the blobs that surrounded interstate exits.

How can we change this dominant pattern? Perhaps we can draw a line around city centers and ban or heavily tax conventional automobiles within that line, while giving financial incentives to city vehicles, such as improved golf carts and electric bicycles. Best of both worlds? Cars and walkability?

Rebuilding after a dam is a productive pattern. I'm familiar with two later examples. Randolph, Kansas and Kaw City, Oklahoma were relocated before dams covered their townsites. Randolph is more like an old-fashioned townsite, while Kaw City seems to have a more suburbanish street pattern. Randolph was relocated in the mid 50s, while Kaw City was around 1970.