Usually I do a sort of follow-up when I have a piece somewhere, but this time, I’m reproducing my latest piece at Resident Urbanist here, because I think this one is important and I want as many people as possible to read it.

Recently, I wrote about the transformation of Amsterdam from an old European city, to a car-choked city in the middle of the 20th century, back to a “European” city. A lot of people are probably unaware that Europe did flirt with car-dependence and automobility, even in the cities, and then—unlike the United States—took a hard look at what that meant and rolled it back.

The car has a place in Europe, obviously, but not a preeminent one as it came to have in the United States. The point is that Europe could have ended up where the United States now is, and up until the 1970s it was on that path. “Europe” wasn’t always “Europe.”

While I was writing about this, I was also thinking of another city that pared back the role of the car, and now has large numbers of blocks that are pedestrianized in the summer, turned over to walkers, musicians, vendors, restaurant dining, and other pleasant street life. That city is Montreal. (Which I’ve also written about!)

This is what Montreal’s seasonal pedestrianization corridor looks like. I took these photos one evening as my wife and I walked something like 15 city blocks from about dinnertime to nighttime.

Montreal is European-ish, but it’s a distinctly North American city, with a style and layout that fits comfortably into the American Northeast/Mid-Atlantic urban corridor. So it’s hopeful to see this sort of thing done in an identifiably “American” setting.

But I’ve been thinking about something deeper here: nothing about this feels radical. It isn’t evident at all that politically divisive fights or, to some people, newfangled ideas about low-carbon transportation went into these urban transformations. One cannot really discern any modern planning concepts which might sound wonky and technocratic if described.

The average casual observer, who doesn’t know what the before-and-after looks like or how the transformation happened, wouldn’t really even imagine this to be a “transformation.” Somehow, despite being so uncommon, this landscape feels completely natural and intuitive. It feels like home. As if we have a memory of it, despite many of us never even having seen it.

I find that really curious and I wonder why it is.

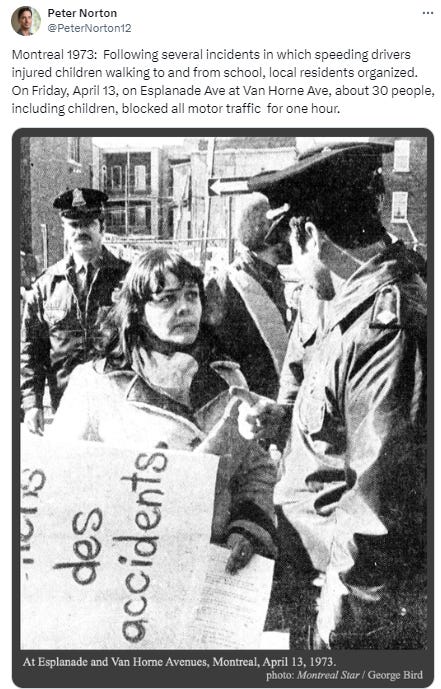

The fact is, there was something “radical,” by some definitions, about how this reversal of the car’s priority happened. In Amsterdam, there were major protests over the death of children at the hands of motorists. There were also concerns, obviously, over noise and pollution. If you had been in the middle of that, it probably would have had something of a “radical” vibe. Protests, chants, signs, marches. If you had to put it into a political category, it would probably reside on the left.

In Montreal, this happened:

And yet the cause, and especially the result, was something completely and utterly normal, leaving no trace of its origins in anguish and protest and political action.

I really like arguments that reframe my way of looking at something, or feel like they reveal some element of reality that is concealed by our political or cultural preconceived notions. I did this here, arguing that children are naturally “urbanist” until they’re disabused of it. What that suggested to me is that, perhaps, “urbanism” is our default setting.

So that’s another one for today: anti-car cities don’t feel radical.

There’s no element of social engineering or ideological weirdness or Brave New World to a city that doesn’t prioritize cars. It doesn’t feel like some sort of utopian scheme. It isn’t Saudi Arabia’s miles-long city (or whatever it is) or a techy “smart city,” or something socially untested like universal basic income. It doesn’t question notions of private property. Those things depart from what many of us think of as reality in some way, or at least they challenge it.

A city that has organized, protested, and resisted cars simply does not feel that way. It is not meaningfully distinguishable from a city that simply existed before the car. It seems as if people can intuit, at a level below politics or even consciousness, that this is what a city is.

Ask someone if they want congestion pricing, or closed streets, or outdoor dining enclosures replacing parking, and they may tell you they don’t. Put them in an urban street where some or all of those policies have been implemented efficiently and pleasantly (sure, you can have some rules on making the outdoor dining structures a little nicer than plywood and plexiglass), and they will very likely like it despite what their abstract opinions about these policies are.

I think this reveals that a city isn’t something we ever designed, per se; it’s the natural form that we built, throughout history, across cultures, over and over again. And even today, after a long interlude of car-dependent land use and car-centric life, we can recognize that form as something basically natural and inoffensive. I would say that we’re drawn to cities, which is a different thing from saying that we like them. Show, don’t tell.

So, show more. If protest and political action are your thing, enjoy the process. If it isn’t, wait for the restoration on the other side.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,000 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Indeed, showing and telling is what we must focus on!

As a professional historian I must point out that humanity built walkable cities from for the last 6000 years, because walking was the only form of transportation available to the 99%. It is only with the development of the horse drawn omnibus in the mid 19th century that there was a serious alternative. Omnibus is a Latin word that means “for all.” Our current term bus is a contraction.

BTW, the first tracks were laid in American and European cities for the horse drawn omnibus, to make it easier on the animals and increase the MPH slightly.

I have read that in the 19th century the average London factory worker walked four miles to their place of employment each morning. I have no way of checking the accuracy of this claim.