I love interesting businesses, especially ones that feel like they provide real value or elevate the place they’re in. (For me, anyway, that rules out those ubiquitous small-town boutiques where everything feels 50 percent too expensive.) This is what many small towns in America need. Purcellville, Virginia is a small farm town, former rail stop, and a now-exurb of the D.C. region, and it has one such cool new business.

It’s a pinball arcade: somewhere around three dozen machines in a simple low-slung building, probably a former office. That’s one of the last things I’d expect to find in a town where one of the neighboring stores is for horse supplies. In this picture, I’m standing outside the door of the place:

In the D.C. area and other big metros you see this interesting phenomenon where the old towns are part countryside and part daytrip destinations for the people in the city and inner suburbs. Not that none of the locals enjoy a round of the silver ball.

What a cool place:

The arcade was started just a few weeks ago by two brothers, one of whom operates a trading card shop next door—mostly Pokémon and sports cards—and while I’m sure they do fine business (they also sell online), the pinball arcade seems likely to draw a broader range of people. It’s not something you can get or do online or in a big-box store. It’s equally appealing to seasoned enthusiasts and competitive players, children and families, and people, like us, just looking for a different thing to do on a weekend.

And the price is right—I wouldn’t honestly be surprised if it goes up a tad, but right now it’s just $15 for unlimited play for the whole day, including if you leave and come back. Which we did (Monk’s BBQ around the corner is amazing, and our $60 sampler plate had enough meat for the next day’s dinner).

Old pinball games, of course, were a quarter, but the newer ones go up to a dollar. So if you spend more than an hour here, you’re definitely getting your money’s worth. (And if, like my wife and I, you’re not very good at pinball, the all-you-can-play deal lets you relax and not think about what each ball falling just between the flippers is costing you.)

I was also really happy that one of the machines I was playing malfunctioned—it had a sudden electrical problem, and all the flippers (four of them!) stopped working in the middle of play. Turns out a switch jammed which blew a fuse.

I say happy, because I got to see a pinball machine fully opened up! I didn’t really know the tables opened up like car hoods!

The fellow in this picture is one of the owners of the place. They’re out on the floor all day, chatting with customers, checking on machines (I also needed someone to pull the plexiglass top off one table and retrieve a stuck ball).

The details of the machines are so cool—all those little custom parts they had to mock up and have made. Take a look at the Dirty Harry table:

There’s a Cadillac-themed table with a little mockup of an engine that does a vroom-vroom sound, a moon landing table with a rocket that angles up, and a bunch of other really fun themed tables.

There’s something about these machines that’s really engaging. The sense you get from playing them is a sense of sturdiness and solidity. They’re always clunking and thumping and whirring and bouncing. It’s a similar sensation to typing on a typewriter.

There’s no differentiation in the user input or experience on a digital device between different tasks. Setting your alarm, calculating a tip, googling something, pulling up your notepad—swipe, tap, swipe, tap. No more clicky keyboard buttons, clacky clock radio dials, different little devices and tools. It’s satisfying, in a deep and almost subconscious, almost metaphysical way, to stand at a pinball table and see and feel the machine work. As if digital devices starve our brains of a certain kind of engagement. It feels like the difference between a real meeting and a videoconference.

Even more abstractly, there’s something very cool, and categorically different, I think, about mechanical engineering versus programming or coding (I think “software engineer” is a misnomer). A coder can basically make a computer do anything, given computing power and knowledge of a programing language. The same experienced computer programmer could program lots of different apps that do different real-world things.

A mechanical engineer, on the other hand, has to have a deep, tactile, embodied knowledge of the specific thing he’s creating. Pinball machines, even those with microprocessors, are full of physical and electro-mechanical parts and mechanisms. You have to imagine what the machine does, and then actually implement it in the real world with physical parts. Each table, where a breezy game might last no more than a couple of minutes, is made of hundreds of little visible and hidden parts, every single one of which had to be made, assembled, and (one hopes) maintained.

You can look at the thing and sort of understand how it does what it’s doing. When something is broken, you can actually see it. Mechanical and electro-mechanical devices are fundamentally intelligible to the average user. Digital tech does something subtle but enormous, in concealing the actual workings of the device in code—something which can only be understood by an arcane priestly class of programmers. (Okay, I’m exaggerating a little bit.)

It’s probably not a coincidence that my favorite machine at the arcade was a 1977 game called Solar City. I believe it’s pre-microprocessor, meaning fully electro-mechanical. The score counter is even a rotary system, like on an old-school gas pump. At the start of each game the score counters clack down to zero to reset, and you can hear stuff inside the machine resetting or getting ready. Half the reason I played it a bunch of times was just to hear that sound.

Pinball was famously banned for several decades because of its association with and use for gambling—in its original incarnation, it was essentially a game of chance. In those days, the tables didn’t even have flippers. As it evolved into a game of skill those laws were repealed. And a game of skill it most certainly is. They even had a tournament the day after we visited.

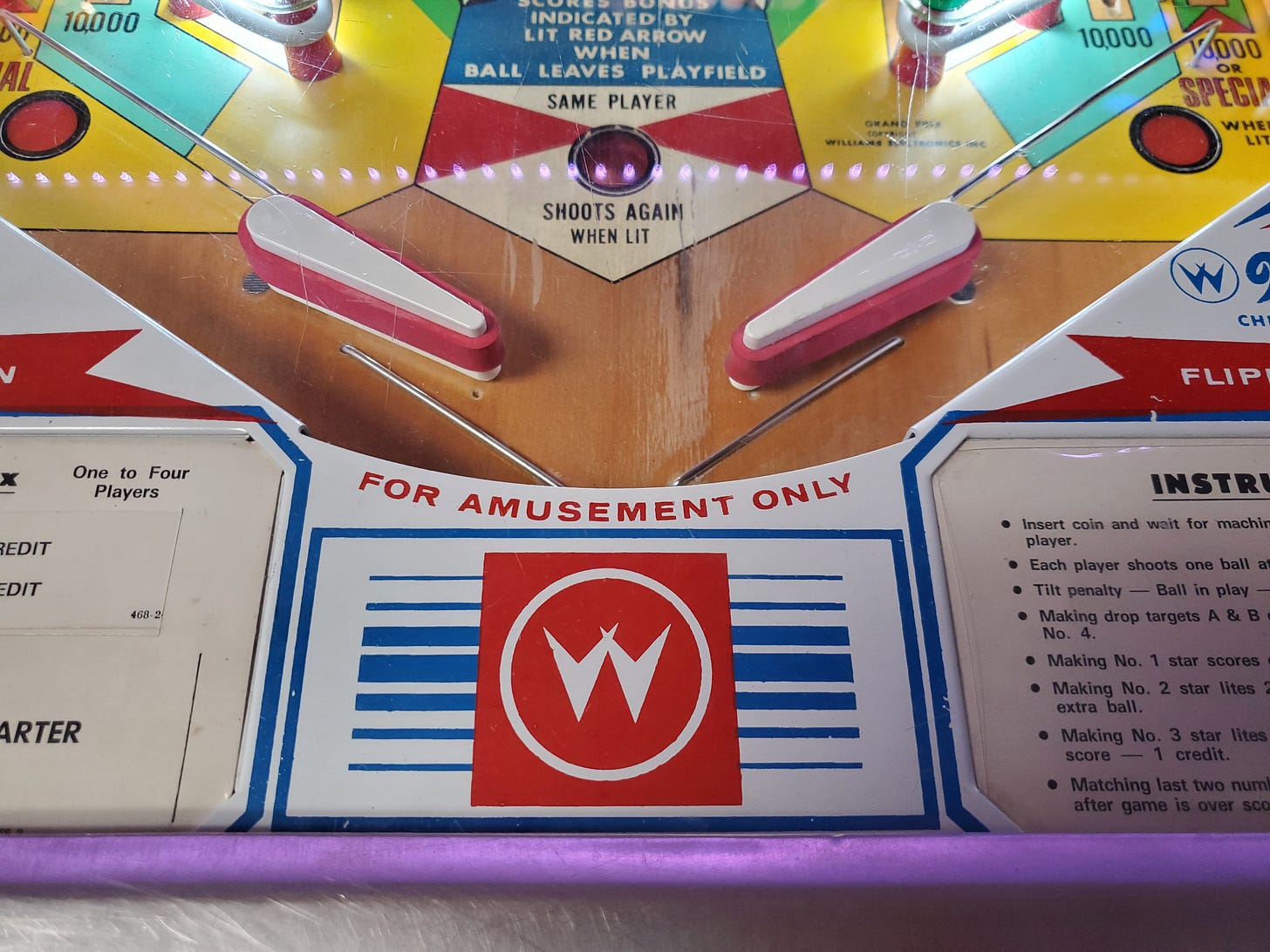

Here’s an older machine, still bearing caution from the gambling days:

Of course, the other element of all this is simple, inexpensive, flexible commercial spaces, and reasonable zoning regulations, that allow a couple of brothers who like pinball to make an awesome business and community space out of that passion.

We don’t know how much we’re missing. But here’s a little piece of it in Purcellville.

Related Reading:

Waking Up to the Joy of Clock Radios

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

OK now I want to vacation in Purcellville!

The comment about programmers being priestly - I think you're spot-on, but it works both in the pagan and the Christian sense of priesthood. A friend of mine wrote about it recently: https://fullstacktheology.substack.com/p/welcome-to-the-priesthood-of-the