Why Does The Bad Guy Feel Like The Victim?

Thoughts on the psychology of sympathizing with petty wrongdoers

My wife and I were at Trader Joe’s recently, in the evening when it empties out a bit. There was a father there with his daughter, who was probably two or three, and when he wasn’t looking she bent down to the basket of fruit snacks and started shoveling them out of the basket onto the floor.

When he saw what she was doing, the father nudged her aside and started putting the snacks back in the basket. A worker came over and stopped him and was sort of hassling him about putting them back, standing there and talking at him and saying how once they touched the floor he couldn’t sell them and they were dirty and might make people sick, but you can buy them if you want, or at least pay for them.

Stuff like this kicks my smartassery into overdrive. “Oh, someone might get sick because it touched the ground? Wait till they find out where vegetables come from!” “You guys can write this all off if you don’t want to sell it, I’m probably making you money!” Or you can reverse the expected roles: “You know, you have a lot of nerve hassling a father at the end of the day like this, you should be ashamed of yourself.” (I don’t mean any of this; it’s like there’s a bad angel on my shoulder whispering it to me in these moments.)

Now I always say how I wish the people working in stores really seemed to care about their jobs, how people who leave frozen food sitting out on the pasta sauce shelf are basically shoplifting and should be fined or kicked out of the supermarket, etc. In theory, I side with the business over the bad customer, and with public order over nuisance behavior. But when I see someone getting reprimanded, I instantly identify with that person. I feel like I am that person, and as if by extension I’m being reprimanded. And I almost feel the desire to do the same bad thing in solidarity, as a statement. Someone getting badgered over some small-time infraction is a much more relatable thing to me than the store or manners or public order. Even though that is where more of my sympathies lie intellectually.

I’m curious to understand what’s going on here, with me, and with other people in public life who seem to have a tendency to defend the “bad” person. Why does my brain perceive that person—the person on the receiving end of punishment or ridicule or scolding or consequences—as the victim? Why do you feel like a comic book hero, an avenger, when you identify with the poor beaten-down guy who is actually scamming society?

Why is the fare evader getting arrested more sympathetic than the millions of paying riders he is stealing from? Why is the guy putting dirty fruit snacks back in the basket more sympathetic than the person who unknowingly handles and eats one? Why is it so easy for us to imagine that shoplifting is some kind of political statement against capitalism or inequality? Why do so many of us take the maintenance of public order for granted, demanding it while also snickering at or attacking what that effort takes?

I guess on some level there’s a nostalgia for that thrilling, relieving feeling of getting away with a little thing. (On some level, I think, Americans see getting away with little things as a core element of freedom. Imagine how authoritarian our country would feel if the laws currently on the books were strictly enforced without discretion or clemency.) That rush of excitement, that frisson of danger, that motivated reasoning making you feel like you’re sticking it to someone and standing up for yourself. (I.e., self-righteousness.)

The people who actually commit crimes most likely do not have such a sophisticated self-understanding of what they’re doing or why they’re doing it. Yet people like me—highly educated people with upstanding personal lives working in left-leaning, ideas-heavy fields—find it so easy, and so tempting, to intellectually exonerate petty criminals and small-time wrongdoers. Why?

Obviously, some of it is political. The conservative in me would practically define progressivism as “making excuses for small-time wrongdoers,” or define away wrongdoing via intellectual sophistry. And yes, I know that’s unfairly simplistic.

It’s also personal. On some level, if the feeling of getting away with something is a thrill, the feeling of getting caught, getting questioned, not being allowed to save some face by simply correcting the mistake, is so hard to bear that I can’t help but define it in my head as injustice. As being victimized. Do you not feel like the victim when a cop tells you you were 15 over the limit and he’ll have to write a ticket? Do you not want to go, “Well, officer, my speedometer is at zero now…?”) It’s easy to say “Actions have consequences,” but it’s much harder to accept the consequences for your own actions.

There’s a tough lesson here. One element of maturity and adulthood is cultivating the ability to override your own reactions to things, to talk yourself into accepting that sometimes you’re the bad guy and deserve consequences. That that is a necessary part of society functioning.

But the difficulty of doing that is why the “victim”—i.e., the petty wrongdoer—is more relatable to me than the enforcer. Because I don’t want to be the guy getting caught, but also, on some level, I want to reserve my right to do the wrong thing. I find it difficult to cheer for someone else getting caught for something I want to reserve the right to do. Not that I really want to do it! It’s just that…I might conceivably do it, and I don’t want any hassle.

I think I would have to struggle with myself to not put everything back and walk out of the store if I dropped a product, put it back on the shelf, and got reprimanded. I think I’d probably want to ask, gee, you guys must be really good, you never fumble anything when you’re stocking? Why don’t you teach me, then? I would have to use a lot of intellectual effort to convince myself that I might be in the wrong.

And I wonder how much of that—the desire to reserve the right to do a thing yourself, even if you will never do it—explains the political impulse to identify with small-time perpetrators over institutions, the idea of public order, or the vast, quiet, law-abiding majority.

Here’s another one, which is less about self-righteousness and a little tricky. An acquaintance of mine recounted a story on social media about a restaurant they all went to in high school or college, I think, and would always order on GrubHub or one of those other third-party apps, but for pickup. One day the restaurant owner kind of yelled at the group, something like “You kids always come in here with this third-party app that practically loses me money, next time why don’t you bother to pick up the phone and order with us directly?” (I’m paraphrasing.)

My acquaintance was chastened by this, and they all started calling the restaurant and placing orders directly after that.

My reaction—at least my initial, natural reaction—would be to say, “Nice customer appreciation there, this is the last time any of us ever step foot in your restaurant!” And, of course, I would feel self-righteous about that.

Who is right in this case? Does the restaurant owner scolding a bunch of college kids break professionalism too much? Or is he entitled to take that tone when he sees these kids losing him money because they’re glued to their apps and phones? Is it reasonable to expect a customer to think, “Well, this app exists for the sole purpose of ordering food and our favorite restaurant is on it, but it’s actually bad and nobody should use it”?

I understand that this is probably true, and that restaurants use these apps with a logic that goes much like “the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.” But my natural sympathies are with the potential me getting chewed out for spending my money the “wrong” way rather than with the business owner getting screwed.

Will this just polarize along the lines of customers who’ve never worked in the service industry versus people who have? I’m curious.

I think I would probably want to talk myself out of the “see you later” position and settle on “he’s a hardworking small-business owner having a bad day, and the apps screw his business, so he wasn’t really accosting a customer, he was just exasperated.” I can certainly understand the frustration of seeing all these orders coming in and all this money passing through your business for nothing.

I understand that “I want to do the wrong thing so I want to let someone else get away with it too” is an ersatz inversion of the golden rule, and the proper application is more like “if you want people to extend you grace and give you the benefit of the doubt, do that for them too.”

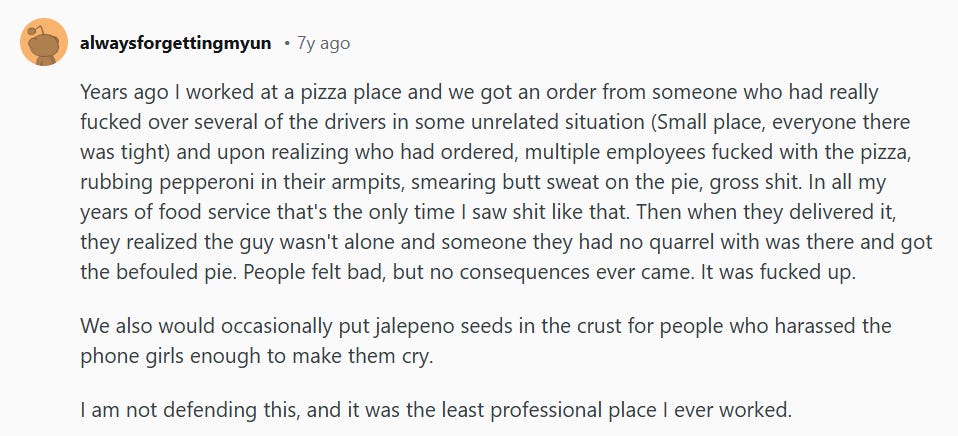

But what about the remote, stereotypical possibility that the kitchen will…mess with your food from now on? That the manager might not be a great man having a bad day, but a petty, unprofessional jerk? Maybe “don’t judge someone by their worst moments” isn’t infallible. Oh, and never look at Reddit, because you’ll find your worst fears confirmed:

This sort of thing is very rare, especially in today’s more sophisticated restaurant industry, I think. The notion that if you complain the cook will spit in your food or whatever is kind of an anti-worker/anti-business stereotype that underappreciates how much most people care about the work they do.

But this raises a very interesting question: what if the cook goes rogue, and my family gets sick? What if forgiving the petty criminal encourages them to mature into a genuine criminal? How do we know when we can be compassionate, or if compassion is in accord with prudence and reasonable risk aversion?

I think I’ll be coming back to this. In the meantime, leave a comment! I’m really curious how folks think about these questions, and how much of this has any relation to political attitudes about crime, law enforcement, and public order.

Related Reading:

Whose Leftovers Are They Anyway?

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,200 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Part of the problem I have with law enforcement is that so much of it is so arbitrary.

Like, to a large extent, I understand the philosophical and legal reasoning behind giving them wide discretion. But at the same time, when all a cop (at least, in many states now, USED to) could say was the three magic words, “I smell marijuana”, and your civil liberties just magically disappeared… well, it’s not unreasonable to feel that that is incredibly unfair, and to want some leniency or a “do-over”.

I live down the street from a police station, which was placed in my neighborhood over 20 years ago to help secure it for the incoming wave of gentrification that I now benefit from. Crime is still a problem in parts of the area. I’ve never had a bad interaction with our cops — unlike back home — and the general sense, justified or not, is that they’re too lazy/racking up corrupt overtime/busy with serious crime to bother hassling minorities too bad [ed: let alone unjustifiably shoot a minority].

And yet, even as I might nod to a cop in the street or at the deli, and generally don’t see myself as a target, I also don’t entirely trust them, because I don’t trust the power they have over me, even if they never exercise it.

I’m kind of the opposite. If somebody is being a jerk in public and they get called out for it, I am completely on the side of the righteous. The dad and the fruit snacks—-I assume they are wrapped in some kind of plastic, so the whole “I can’t sell these, they’ve touched the floor” seems like an overreaction. But good for that store employee who at least tried to make the connection in front of the kid that their behavior affects others.