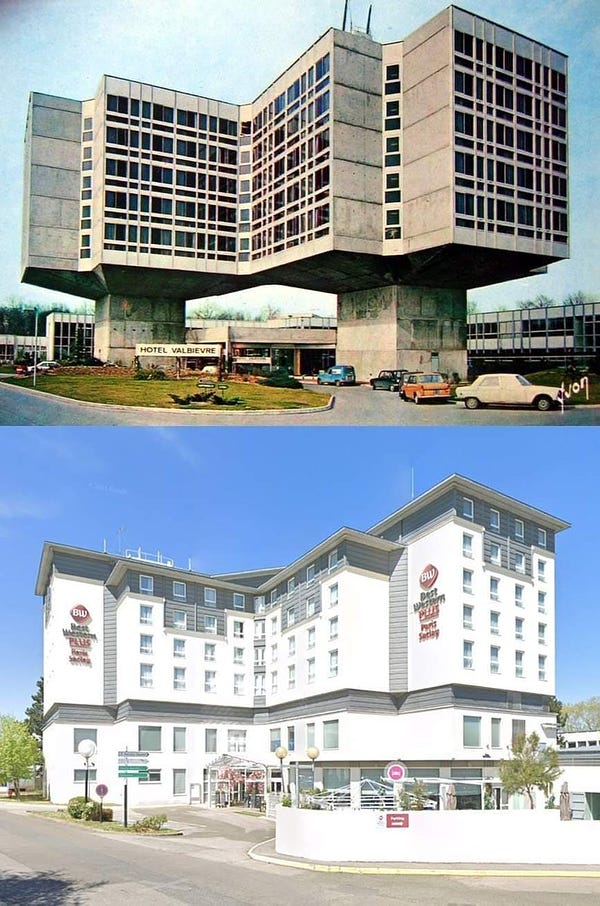

This is a hotel in France, just outside Paris:

It used to look like this (I still remember seeing those old Holiday Inn signs here and there in my childhood):

But this building has a secret. It has always been a hotel, and it has not been expanded. But it differs dramatically in one way from its original appearance.

At least, I’m pretty sure it does. I was not able to find an actual vintage photograph of it, only illustrations. There is a mildly Twitter-famous image showing the building’s before and after, but I could not find any reference to this project on the internet that didn’t reproduce just that image.

Here’s the old:

And here’s the old and new, from an interesting Twitter thread in semi-defense of brutalism:

Here’s a Facebook page (in Spanish) where this building is being discussed.

Me, I’m conflicted. The old version is cooler; the new one is typical, bland chain architecture. But brutalism does give me a feeling of subconscious dread. Not conscious, because I sort of like it! But I’m unable to like it fully. I think it’s okay as art, but I’m not so sure about it as architecture, which is to say public art you cannot take down or reserve in a museum.

Still, it’s almost certainly the case that many of us will miss it when it’s gone.

I just hope the beds weren’t like the old walls.

Related Reading:

What Do You Think You’re Looking At? #24

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 500 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Large-scale brutalism seems to have two distinguishing features.

The first feature is the use of raw concrete (béton brut). Raw concrete was cheap and fast--useful in a postwar period where massive rebuilding was necessary in many European cities. Trying to find make "art" with it was attempting to make a virtue out of a necessity. But raw concrete was not aesthetically appealing to most people, and it gets less attractive as it weathers. However, I don't think this is why so many people hate brutalism with such passion.

The second feature is the use of overhangs and cantilevers to create massive structures that appear to dominate and even threaten the relatively tiny people walking below them. These designs often look actively hostile. And I think it's this hostility of design that draws such hostility in response.

Brutalism to me has always spoken of power. Specifically, power applied in a nihilistic way. A "I'm so powerful, I will build a building that exudes that power but utterly lacks refinement and charm." Prime example? J. Edgar Hoover building