I sometimes wonder how my personal enjoyment of driving, and my reliance on a car for much of my work, lines up with what I write here. I take transit when it fits my schedule and when it drops me where I need to be, but I do rather enjoy a long drive, and transit often fails to meet those criteria anyway.

Some of my fondest memories are tied up with my car, a humble Hyundai that I took to grad school and have used gently but regularly for many years. Long, neon-lit night drives after long evenings of studying; trips out to the Virginia countryside; lunch breaks on work-from-home days spent walking around a supermarket or trying out a restaurant just a little too far to walk to.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with this. In fact, I think there are many journeys and experiences for which the car is essential. Driving can be a joy. It can reach places, enhance freedom of movement, serve as a joyride or a nighttime exploration or an express pioneer wagon to a reinvented life.

But the tragic irony is that those purposes for which the car is most uniquely suited are exactly those for which we use it the least.

Maybe we got it right the first time, a century or more ago: cars are great for leisure and exploration and sport, but not so great for commuting, running errands, and other everyday tasks, at least in areas that were already substantially built out before widespread car ownership. It was once common, for example, to own a car for weekend drives, but commute on the trolley.

But we were sold—and to our discredit, we bought—gridlock and rush hour and ten-minute trips for a half-gallon of milk and 30,000 Americans violently killed each year under the banner of exploration, freedom, and the open road.

We created a zero-sum built environment and an attitude to go with it, in which one more person is not an asset but a liability. We normalized the desire to be the last person to move in and to pull up the housing ladder. And we birthed a new malthusianism, which sees the struggles of the next generation of young families as someone else’s problem, or even as a good thing. Too many people.

What we almost always really mean by too many people is actually too many cars. But this usually goes unstated and unnoticed. In the popular imagination, new people mean new cars as surely as marriage means babies—maybe even more surely. Many of us would no more part with a car than our own feet. (A pity, because if we managed to do so, our feet would prove more useful than we knew.)

This conflation of the car with the person may be blamed in part on the automobile industry, and even more so on zoning codes, the arcane but vital DNA of the built environment. By dictating lot sizes, parking-to-square-footage ratios, and other such seemingly wonky details, most zoning codes have effectively outlawed development at the human scale, in the traditional manner. Most of the most-loved places in America could not be built today. Perhaps at one point this was chosen or desired, but such codes are now so ubiquitous that relatively few Americans have lived under a land-use regime that permits anything else.

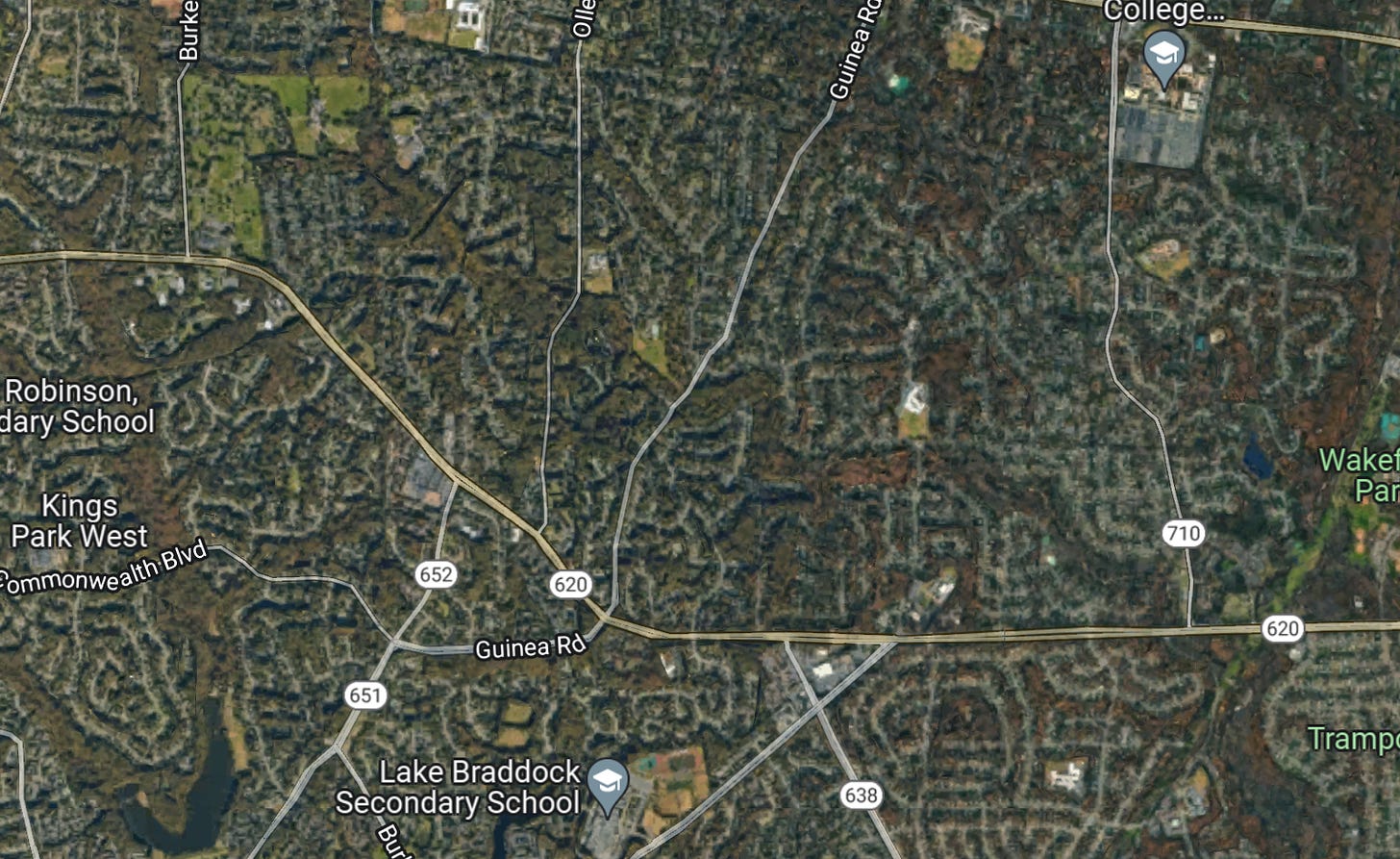

The insight that sprawl, rather than density, causes traffic is not necessarily intuitive. But it makes sense. When the built environment is designed such that nearly every errand or recreational activity generates an automobile trip, the result is traffic. When stores are supersized, with trade areas of several miles or more, the result is traffic. Take a look at this satellite image of a pleasant, leafy part of Northern Virginia.

It looks spread out, almost remote, yet it regularly sees heavy traffic. Those are related. When I drive through here—for those of you who know the area, Braddock Road is the main arterial—I feel a certain uncanniness, like I’m in a computer-generated world where somebody forgot to fill in some of the details, or like someone in a Twilight Zone episode.

Those people, spread out across a lot of sparsely populated land, end up funneled into a small handful of roads and stores when they want to get or go anywhere. Traffic. Not because of too many people, but too few people, and too few places to go.

I’ve written about this particular idea before, here and here. Here’s a snippet from one of these pieces:

As we waited to exit from one of the multiple exits, none of which were quite easy to locate, my dad said, exasperated, that everything here was built too jammed together. “Jammed together?” I said with surprise. “Everything is so spread out!”

I realized that we perceived this planned chaos of the modern commercial strip very differently. My dad saw the crush of traffic and the high intensity of navigating this landscape, and read it as crowded and pressed together. I saw so many distinct properties islanded by dangerous roads, and the near-impossibility of leaving your car and accessing multiple properties or of crossing the street, and read it as distance and separation.

Now none of this is new to urbanists. But I am sure much of it is new to most ordinary people. Some people are skeptical of things like New Urbanism or Smart Growth, viewing them as top-down, ideological, busybody planning philosophies. But the ideology—of rather recent vintage, and springing in part from the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt—of the suburban status quo is less visible, though far more radical.

It is not possible in most places to eschew both the suburban status quo and the more modern self-consciously urbanist approaches and “just build like we used to.” We have buried the possibility of small-scale, participatory, entrepreneurial, incremental development under an avalanche of regulations that work in tandem with large developers and large projects.

It can be lonely knowing these facts—and they are mostly not characterizations, but facts. On the other hand, it’s extremely heartening to have found such a large and diverse audience for these ideas here at this newsletter. You obviously don’t know each other (most of you don’t—some of you probably do!), but I can tell you that you’re from all across the political spectrum, for starters. Thank you, as always, for reading.

I know I’ve combined discussions of cars and land-use here, but transportation and land use are tied up in so many ways that I can’t really talk about one without the other. Here’s a longer piece I wrote that you may have missed on some of these themes (which also began as a piece about transportation and ended up being more like this piece).

Now, I’ll leave you with a question I’m still chewing on, that I raised briefly in a different piece and would like to keep thinking about. I’m not sure if it contradicts some of what I wrote above about the centrality of zoning in our land-use and transportation problems. Which is why I keep coming back to it. I wrote:

The trade areas of these large stores and shopping centers are meant to be large, meaning that while they certainly serve locals, they are not neighborhood businesses; the parking requirements are meant to be overly generous; and the highway itself is designed for fast driving. This is not a scale or a built environment that is particularly conducive to thriving small businesses or close-knit communities.

The question is: to what extent does economic centralization relate to sprawling land use and car dependence? Is what we think of classic urbanism an actual approach to land use at all, or a figment of a more local, fine-grained economic reality? I’m wondering something like, “what came first: Main Street or the small grocery store on Main Street?”

Can we build in that manner again when business exists at a much larger scale than it did in those days? How much of the sometimes perceived failure or mediocrity of urban-style “town centers,” for example, is the desire for a scale and a type of local business that has increasingly been squeezed out?

As I often say, none of this would have ever occurred to me to even wonder about four or five years ago. Thinking about these issues sometimes feels like opening up another sense, a way of perceiving things. It’s fascinating, and I hope it opens things up for you too.

Related Reading:

Taking Off the Car Blinders, Opening Your World

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive of over 300 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

I am enjoying your platform. You put in some form of logical progression the random thoughts I have about cars and stores and planning and all that stuff. A conversation about "New Urbanism" cannot be has without talking about the New Nibmy's, those that oppose growth, even smart sensible growth, as gentrification. Have you explored any of that theme in your musings?

thanks for the thoughtful approach,

Ric

I've come to see auto dependence through a different lens lately. Land development is always dictated by transportation infrastructure. Seaports, canals, railroads, post roads, the interstate highway, airports... Each kind of city is built on an underlying network of ships, barges, trains, carriages, cars, trucks, and planes. As each new form of transportation peaks and ages the associated infrastructure becomes too expensive to maintain relative to its ongoing productivity. So the seaports continue to exist, but in a reduced form as the excess docks and waterfront warehouses are abandoned. The truly vital canals that transport wheat, soy, and iron ore in bulk are still with us, but the majority were filled in decades ago. The streetcars that ran through our early suburbs served their purpose (to add value to cheap land by providing a commuter rail link to new homes) and then contracted as the cost of upkeep outstripped revenue. There will come a day when the cost of keeping every far flung cul-de-sac and suburban side street paved will no longer be financially viable and triage will set in. That process is already underway in poorer neighborhoods.