Let me suggest something: there is no such thing as a “strip mall.”

The term “strip mall,” sort of like “sprawl” or “suburbia,” is used very broadly, and it erases a lot of subtle differences between different physical forms for retail. I like to think about this stuff in evolutionary terms, because the iterative process by which products or designs or building types evolve actually looks a lot like biological evolution.

If you read Main Street to Miracle Mile by Chester H. Liebs—a fascinating book that looks at the development of common roadside architectural forms—he suggests that the strip mall is effectively an urban block that has been heavily adapted to cars. He identifies the streetcar commercial corridor as the missing link, of sorts, between the classic urban block and the modern suburban strip mall.

Like the actual fossil record, the roadside fossil record of old architecture is incomplete, as buildings have been renovated, expanded, or demolished over the years. But in older suburbs, a lot of “transitional species” are still standing, and they display an unmistakable mixture of classic urban features and car-oriented suburban features. I find this really interesting. Here are some illustrations.

I’ll start with a couple of structures in Arlington, Virginia. I’m not sure if streetcars ran directly along here, but they ran in the general area, and you can see how these are sort of proto-strip malls.

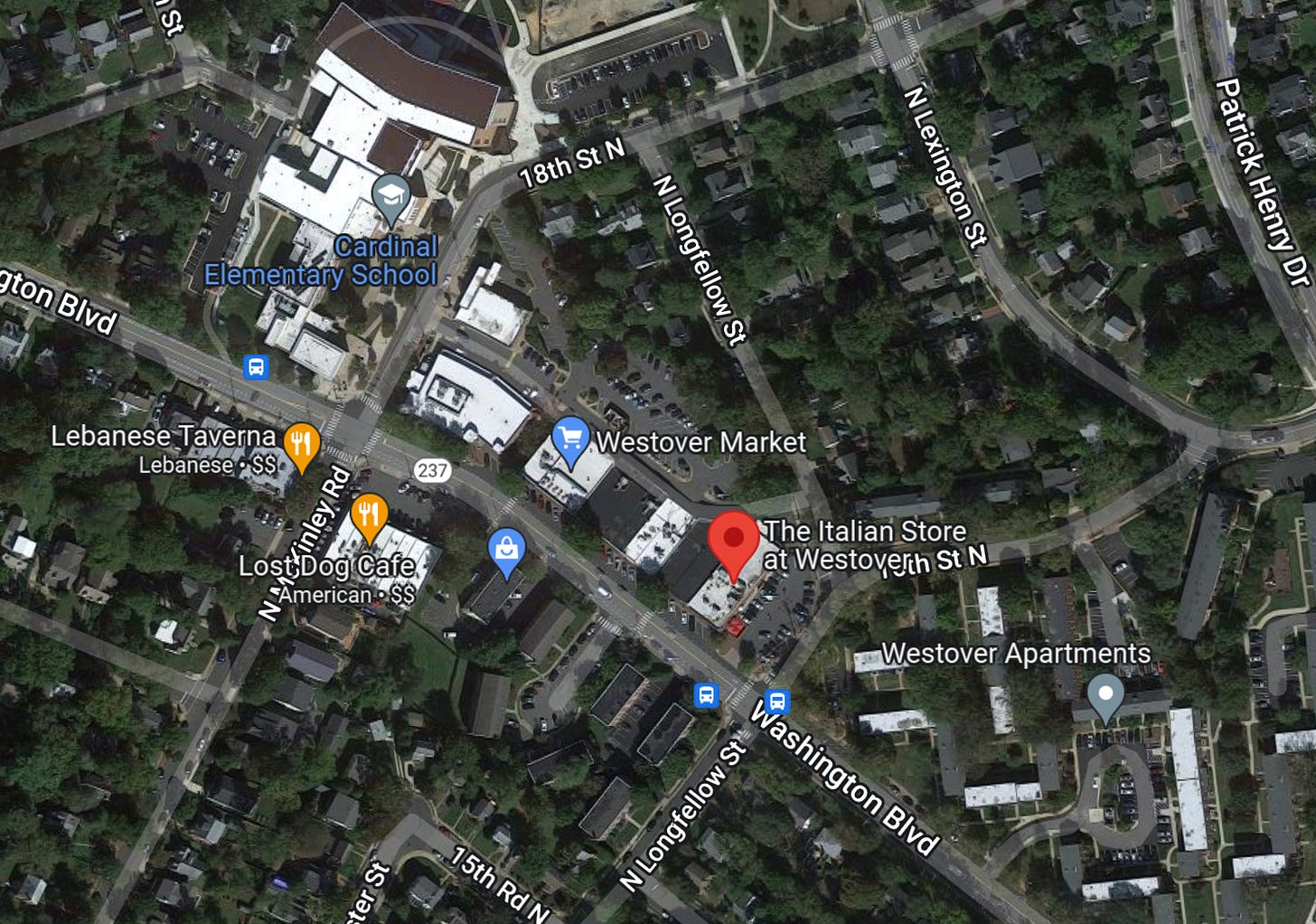

Here’s one that looks, from the ground, like a little Main Street-style commercial block. There’s even a wide brick sidewalk and street trees.

Here it is from the air. You can see that the whole “block” is a single, freestanding building, surrounded by a school and a mix of apartments and detached houses. The commercial strip has angled on-street parking, and a small parking lot off to the side.

What is this? I don’t know—what was the archaeopteryx?

Here’s another one in Arlington:

Here’s something similar in suburban Alexandria. Notice the fancy façade work on the Goodwill store, and also the fact that the façade is not continuous. This little shopping center was trying to look like a little segment of Main Street.

Some of these building types in Arlington/Alexandria go back to the 1930s or so. Eventually this form pops up on bigger highways, on suburban car-oriented commercial strips rather than in little neighborhood shopping centers or on old streetcar routes. Here’s one on U.S. 29, a U.S. highway running into D.C. It was built in the 1950s.

Not too far away on U.S. 50, in Falls Church (Fairfax County, Virginia now), there are some very similar structures, but with larger parking lots. In the picture below, there’s a lot of parking lot behind me, but there are still the angled on-street style parking spaces up against the building.

And I noticed, at the far right edge of this strip, one very neat “urban” feature that is still retained here, but is much less common in modern strip malls: a store with an angled orientation on the end, mimicking an urban corner store. I’ve seen this a few times in the area.

Here’s an interesting one further south, along U.S. 1. This is actually laid out along the access lanes parallel to the main portion of the highway. In other words, the space between the stores and where I’m standing is a lane of traffic. It’s almost like a really stretched out, high-speed Main Street.

One more thing: the employees-only, loading/unloading area at the back of these strips, usually blocked off from the surrounding neighborhood by a fence or planted buffer, is effectively an alleyway.

This gradual evolution of suburban landscapes might all look the same if you’re comparing it to, say, the best European cities. It’s all “suburban sprawl” and these are all strip malls. But the distinctions—from the scale and size of the businesses, indicating how friendly the spaces are to small business owners, to the walkability of the surrounding areas, are real. And over time, the tendency has not gone in the right direction.

Step by step—more parking spaces, larger parking lots, deeper setbacks from the road, larger structures for chain anchor stores, etc.—the urban block evolves to adapt to the car more and more, until it becomes almost unrecognizable. It looks like a completely different animal. But some of that urban-block “design DNA” is still in there. Streetcar corridors were practically “real” urban blocks, and modern strip plazas are very, very different, but these pictures show a little of what came between.

Related Reading:

Spread Out or Smashed Together?

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive of nearly 300 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

I see a slow incremental evolution from cookie cutter suburbia to some version of clumpy urbanism within the sprawl.