Race You To Vine, Winner Gets A Walnut

Duplicate streets and thoughts on the nature of towns and cities

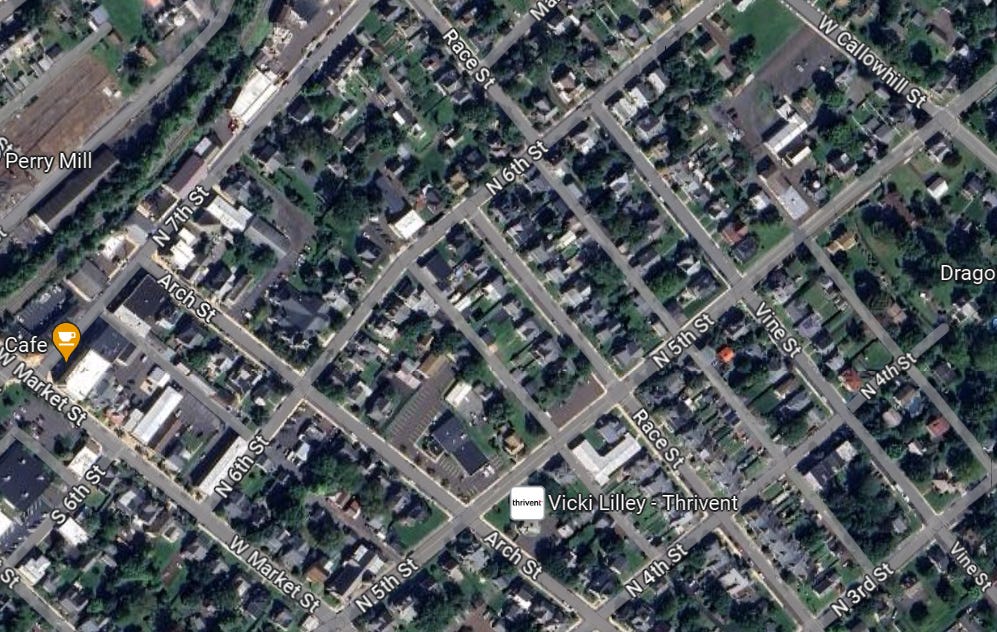

Race, Vine, Walnut. Those are three street names I’m familiar with from Philadelphia, which I noticed clustered closely together in downtown Cincinnati the other week. The tree names are common enough, but Race and Vine seem more unique, and I immediately thought of Philly.

Missing in the overlap are Elm (Cincy only) and Market, Arch (renamed from Mulberry), and Chestnut (Philly only). I had thought Arch was named for the Chinatown arch, which sits at the intersection of Arch and 10th, but apparently not:

Formerly known as Mulberry Street (one of William Penn’s streets named for trees, this one was named for the Mulberry tree). Became known as Arch Street because Front Street formed an arch or bridge when it passed over Mulberry Street, with the latter going down to the riverside to form a public landing up until the 1720s. The name nevertheless stuck, long after most people had forgotten the arch itself.

The Chinatown arch, which I think a lot of people call a gate, is formally called the Chinatown Friendship Arch, which is either a coincidence or an attempt at retroactive continuity.

This is a neat bit from a blog post I found:

Nathaniel Burt wrote in ‘The Perennial Philadelphians’ (Little, Brown), pp. 529-30:

“The only area of the city that ‘Old Philadelphians’ really consider Philadelphia is that narrow belt that extends from the Delaware to the Schuylkill, south of Market and north of Lombard. The rhyme ‘Chestnut, Walnut, Spruce and Pine; Market, Arch, Race and Vine’ expressed the ultimate limits, north and south, of an ‘Old Philadelphian’s’ personal knowledge of the city—and Race and Vine were only included because of the rhyme.”

Cincinnati is also somewhat notable for having an actual “Main Street,” which in big cities often ends up being called something else. However, Main Street today isn’t the central street, Vine is. But Main was originally the central street!

I did some reading about this cluster of street names, and why it is that so many towns and cities share the same general naming scheme (presidents and trees intersecting with numbers), often with the themed streets running in the same direction, and sometimes with the trees even in the same order.

The academic answer seems to be that Philadelphia, as one of the first planned gridded cities in what would become the United States, sort of set the pattern. It was easy to just copy it. (Alexandria would also count as a very early gridded American city, but its naming scheme is pretty different, though probably duplicated in some Southern localities.)

Where does the name “Race Street” come from? Surely not some kind of nod to race riots? Nope, although I think I thought that as a kid! It’s named after actual racing—horse racing, that is. In Philadelphia, horse races were run on that street and the name stuck and became official. This anecdote transferred to other cities with a Race Street—people in those other cities will also say it was named after horse racing—even though it was most likely named after Philadelphia. Horse racing once removed.

Here, for example, is a neat article on trying to track down the origin of Race Street in Urbana, Illinois (the conclusion is that it’s lost to history, though it may have been taken from the plat of a nearby defunct town, which in turn was probably substantially lifted from yet another town or city):

While we waited to hear back from Danville, I decided to do some research on the name ‘Race Street’ in general. I found that it was a commonly used name for streets in early American history along with other streets like ‘Washington,’ ‘Market,’ and ‘Main’ streets. Market and Main derived their names from the activities done on those streets, and it seemed Race Street did as well. In Philadelphia, for example, Sassafras Street was renamed Race Street in 1800 because citizens regularly used it for horse racing. Interestingly, Race Street in Philadelphia runs perpendicular to Cherry Street, and in Urbana, Race Street runs perpendicular with Cherry Alley.

Here are a couple of online threads about this question of repeating street names, with this interesting comment:

Americans were settling a new country and establishing townsites quickly. Instantly, compared to European village growth. The "democratic" and rational system William Penn used in Philadelphia was appealing to surveyors laying out rectangular plans; numbers in one direction and trees in the other. In many cases, the trees are even in the same order as Philadelphia.

West of the Alleghenies many townsites were laid out by railroad draftsmen, sometimes at a drafting table thousands of miles from the townsite. They tended to use standard plans with standard streetnames, or to borrow from towns they knew well. From the 1830s, presidential streetnames became popular but fell out of favor around 1900 as they got to presidents of recent memory who weren't always remembered fondly.

One other anecdote: apparently, Portland, Oregon is named after Portland, Maine, with its other prospective name being Boston (it was settled by a pair of New Englanders.) A coin flip settled the competition in favor of Portland.

Finally, here’s the little Bucks County borough of Perkasie, historically a town of about 2,000-3,000 people. And here are those core Philadelphia streets, in the same order as the big city (Market, Arch, Race Vine). Walnut and Chestnut precede that cluster to the south, also in the same order as Philly! (They don’t fit in the screenshot.)

The deeper reason for this duplication is that the simple gridded, planned city—in some ways an innovation and in other ways just another variety of traditional urbanism—was an easy and adaptable pattern. Townbuilders saw no need to reinvent the wheel as the country grew and cities and towns sprouted up by the hundreds.

There’s something almost spooky about the idea that dozens of very distinct places that have grown their own look and feel and identity over the decades or centuries basically started as carbon copies of each other or of a few pattern-setting cities. Isn’t it kind of wild just how much difference there can be in places that share the same format, the same skeleton, the same origin?

I think this also demonstrates a point I’ve made before: that the distinction between “city” and “town” is ahistorical.

For example, my little Central New Jersey hometown of about 5,000 people (today) has a Broad Street and a Park Avenue: both iconic New York City street names. Many other small towns and cities copy that cluster of Philadelphia street names. Nobody was saying at that time, “We’re just going to be a small town, we don’t want to imitate the big city.” If anything, it was more like, “We hope we’ll grow like the city, and we’re even going to name our lowly little streets after their grand streets.”

The existence of an imitation New York City street in a “quiet” “quaint” “small town” seems contradictory—until you realize that those descriptors came later, and that they misdescribe what these places actually are and why they actually exist.

The difference between towns and cities is something we see looking backwards, imagining that those urban settlements which grew to a great size, and those which did not, are and were different creatures. But these are differences of degree, not of kind. I guess In a philosophical sense, these settlements are all the same thing, and their differences are real but also pretty small compared to their similarities.

Whenever I really pay attention in an old town or city, I get this feeling that these are places we don’t fully understand—that we view them with a certain remove, as artifacts we happen to have inherited, and not as the products of quite the same culture and civilization we are today. But I don’t think it has to be that way.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,000 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Growing up in a town where Main Street actually was the primary downtown commercial street, I've always found it amusing how "Main Street" in many West Coast cities (Seattle, Portland, San Francisco) isn't anything particularly special today. It doesn't have the same cachet when there are multiple major commercial districts. We much prefer Broadway and Market 'round these parts.

Haha, I’ve BEEN on Race street in Urbana and wondered what the heck that was about. (UIUC grad)