Now, Folks, It's Time For "Who Do You Trust!"

Scammers, like traitors, degrade society, and their marks being dumb doesn't excuse them

So one reaction to this story in New York Magazine’s The Cut is “this woman is an idiot.” The other is what I’m going to write here.

I have no stories about scamming myself, though I do recall one evening, in college, getting a call from myself. My own name and number showed up on my cell phone—the same number keyed to that cell phone. I picked it up, out of curiosity, and there was nobody on the line. It called another couple of times, which I didn’t pick up. I googled the phenomenon and didn’t find anything terribly interesting. I still have no idea who or what it was, or what possible scam it could have been tied to. It never happened again.

But I read the whole piece, and I had a lot of thoughts. Yes, don’t pick up unknown numbers, double-check on your own account or with customer service if a company purports to call you about money (or anything), don’t trust anyone who warns you not to contact a lawyer. But stopping there is a neat, clean way of pretending that this massive and worsening problem simply doesn’t exist.

My first thought is that—given that the scam’s hook was about an Amazon account—Amazon does not do enough to stop this. Yes, they tell you that they won’t call you about such matters, and as far as I know they observe that rule. (As many commenters observed, it’s tough to get a hold of a person over there at all.) But shouldn’t Amazon’s leadership be outraged that so many crimes are being perpetrated in the company’s name? Using its popularity and market share to fleece loyal customers? Where is the urgency?

There’s that. But there’s also the fact that companies like Amazon frequently look and feel scammy, which makes it harder to discern when you’re dealing with an actual scam. Think of the customer service agents who give you different answers to the same question, as if there isn’t a set of company policies. Think of how big companies conceal the customer service phone number, increasing trying to shunt calls over to chat, and even—though as far as I can tell, not Amazon itself—AI chatbots. Like Air Canada, whose now-disabled AI chatbot invented a policy that didn’t exist and got the company successfully sued.

Or how Amazon administers its third-party seller accounts, for ordinary people who sell items on the platform. They may or may not be one per person per lifetime, or one per household. They can be shut down if you live in a dorm or multifamily building and IP addresses are confused with the IP address of someone whose account has already been shut down. There are those notices you get about account closures from companies not being appealable, about having no right to know why an account was closed (I’ve seen this language before, but I’m not sure if Amazon does it). If you manage to get a human being on the phone, maybe it is appealable!

Read this Reddit thread about Amazon’s behavior when it comes to account closures. The actual Amazon people make less sense than the scammers! Here are a few tidbits:

TL;DR: Amazon closed my account while a refund was in progress and it took three months to get my refund after so much back and forth via email until my account was randomly opened, allowing me get my refund through live chat

After hours on the phone, sending email to Jeff, andy and dave, and a gazillion emails to account-alert@amazon.com (<-- that's the Acct Specialist email) nothing. Then, I submitted a complaint to the BBB , I amazon account was reinstated , af ter 3 business days.

Lol they do this to sellers a lot who have 5-6+ figures in inventory at Amazon locations. Really helps you sleep at night.

Some of this is mere annoyance, but some of it involves Amazon effectively cutting you off from your money and your inventory, which some sellers store warehoused with Amazon even though they are the sellers. The actual legality of all of this is…I don’t know.

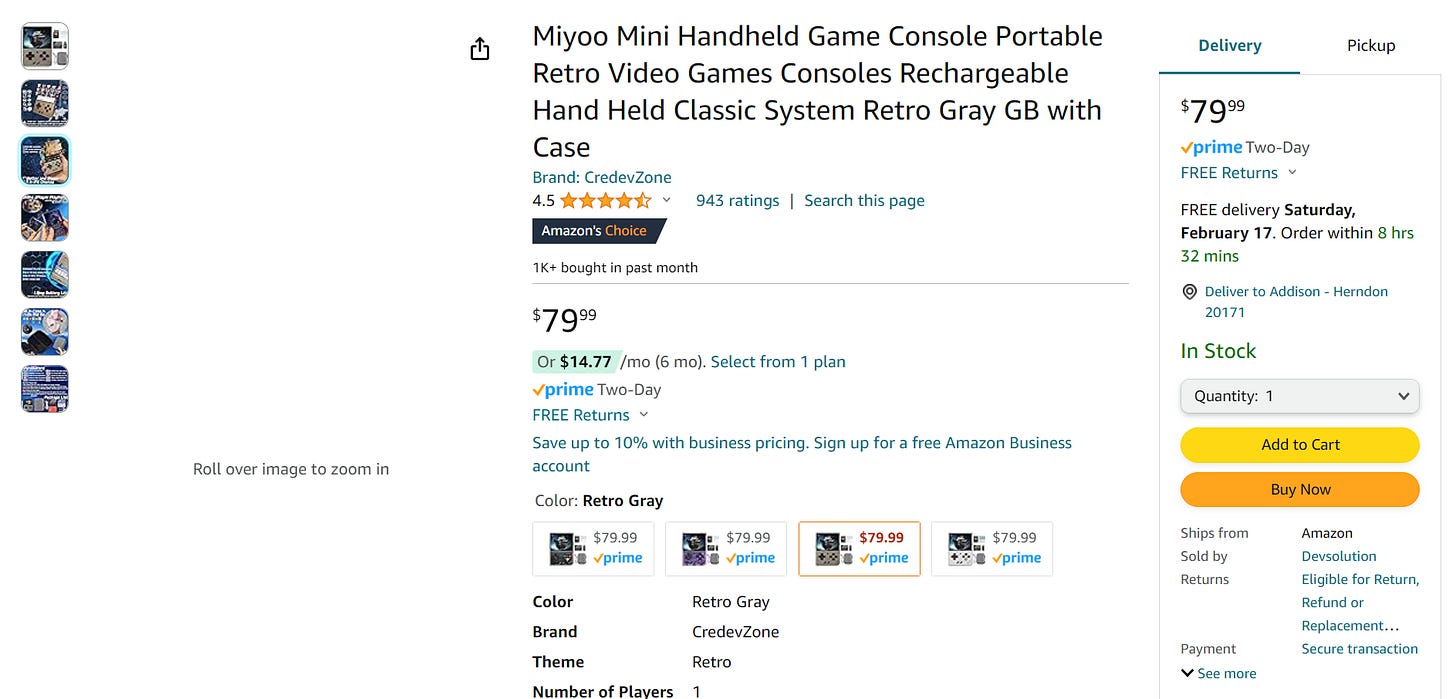

And then, of course, there are all the straight-up illegal items Amazon sells! Look at just one of probably hundreds—a Nintendo Game Boy clone packed with ROMs and emulators for almost every game console ever made, plus the arcades:

Okay, it isn’t sold by Amazon, but is sold under the Prime logo and shipping scheme. But maybe Amazon just missed it? Oops, look what its predictive search recommends when you simply type in “gameboy”:

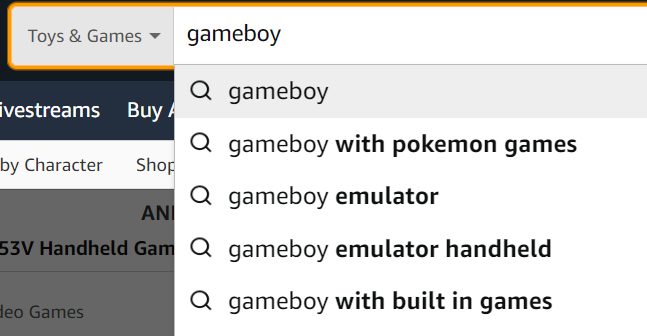

Want a little more? Here’s one with clear screenshots of actual Nintendo games!

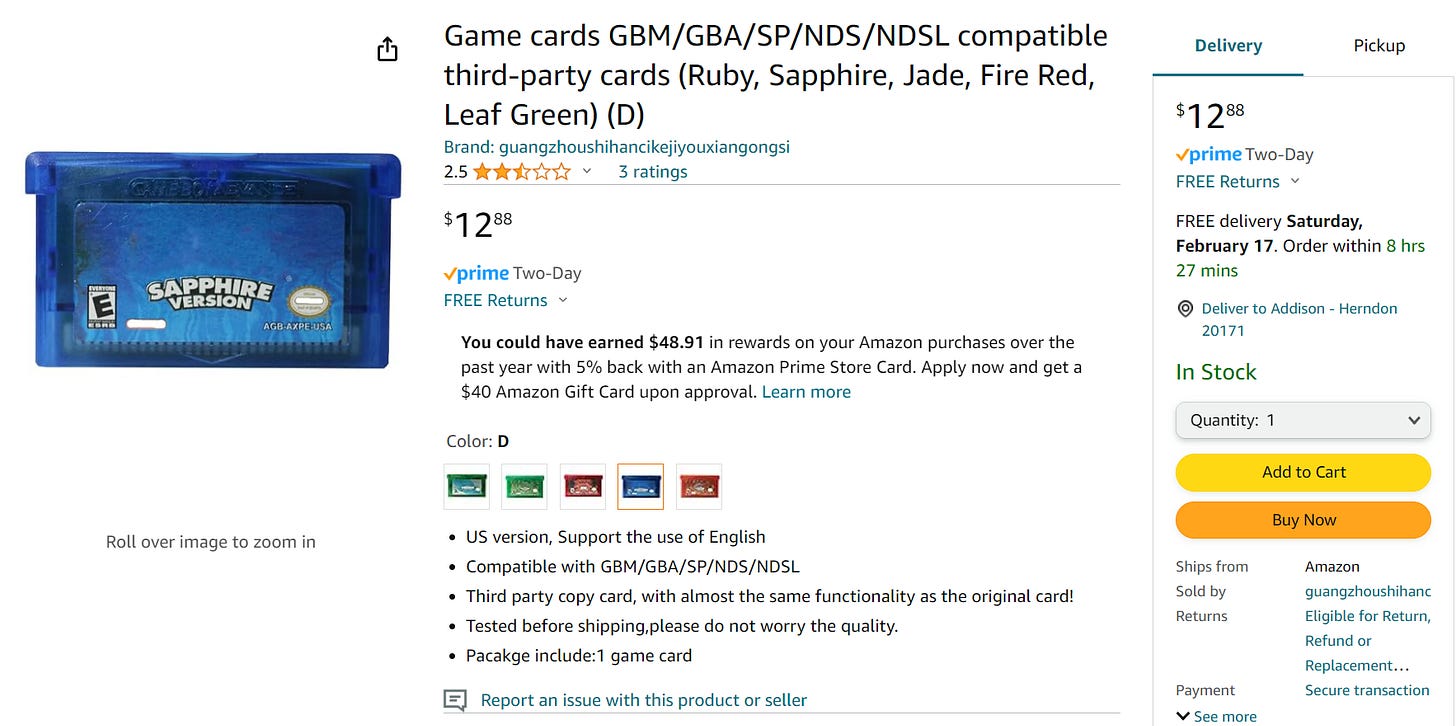

Finally, here are some really bad attempts to disguise counterfeit Pokémon games for the Game Boy Advance (which are really expensive):

Again, Prime. Anybody would take that to be Amazon’s official stamp of approval.

It’s not unknown for people to get legal notices from Nintendo over downloading video game ROMs illegally. This isn’t a legal gray area. Is it even technically legal, I wonder, to buy and possess one of these items? I don’t see how it could be. Downloading this stuff on your own computer is one thing, however; the world’s largest online retailer selling them under its fast-shipping membership program is something else.

One more little bit, not from Amazon: one of my friends had his Airbnb account permanently closed because he was scammed, and the company kicked him off the platform for whatever the person who stole his credit card information did. He tried to contact the company, and they basically wouldn’t tell him anything. No appeal, no explanation, locked out of a widely used platform for life. Insane.

So: is it that hard to believe that an Amazon agent would call you to alert you about some issue with your account, against company policy?

The consumer-issues part of this out of the way, the other thing I kept thinking was how the article read like a plot from a spy movie. Or rather, how the scam was designed to make the victim feel like she was in a spy movie. I think we like the idea of living in a spy movie. Life is boring. Spy movies are fun. My dad always says people have trouble distinguishing fiction from reality. He says that, for example, when someone in a film holds up a pistol and sprays hundreds of bullets, or when someone gets thrown through a concrete wall and then gets up and keeps throwing punches. Maybe we can’t tell the difference. Or maybe we don’t want to.

But once you think of it this way—sophisticated financial scam as action film brought to life—you see how much these scams rely on tropes from the entertainment world: cash in envelopes, government agents, phones that magically transfer everywhere (one single five-hour phone call spanning Amazon, the Federal Trade Commission, and the CIA), SUVs with tinted windows, detailed but tight-lipped instructions about not looking at the driver and how exactly to hand over the cash.

Not to get into politics, but this reminds me of a really fascinating piece I read awhile back about the whole Qanon thing. The author wasn’t just making fun of it, and was certainly not endorsing it. He rather broke down how the whole thing was a kind of video game or film brought to life. The takeaway was, real heroes and villains—real whistleblowers—don’t leave cryptic clues. They don’t operate like the Joker, or like confidence men. Only conmen act like conmen.

Real life, especially things involving government at the level you or I would likely ever interact with, are boring. Mind-numbingly boring. Government is the sloth DMV scene in Zootopia, not secret cabals and conspiracies involving hundreds of people across government and elite corporations.

Tied, perhaps, to the boredom element is the whole remote work shift. The woman in the original piece describes herself as a freelancer, so she probably would be working at home anyway, but one of the comments on the story was really interesting:

Contrary to the author’s belief that single, lonely people are more gullible, it seems targeting stay-at-home parents of young children would pay off for the scammers. You’re bound to find someone eventually who is exhausted, overworked, and unfamiliar with how slowly the government gears usually grind.

This is really interesting. One of those second- or third-order effects of the pandemic. You get someone who cares deeply about their family, who experiences a certain chronic lack of social stimulation…and you can kind of get falling for a scam, being inside your own head so much.

So the whole stay at home thing. This is one of those very subtle and probably not measurable fallouts from the pandemic. The increase in loneliness, time spent home, alone, mentally isolated. Think of how differently that story would play out if she had taken the call sitting at a desk in an office, rather than at home, alone, with her young son.

I do wonder what the long-term effects of people spending far less time with other people will be. Other people help you level, stay grounded. Engage your brain. Your brain wanders. It gets bored. It looks for things to latch onto to fill that need for stimulation. In fact, here’s a comment on the piece I saw after I wrote this, which exactly confirms my supposition!

This was tough to read. I am a lawyer and received a very similar phone call a few years ago. Maybe I was distracted when I picked up, or maybe the person on the phone was very convincing. Same story about a federal investigation into a burned out rental car found at the border with drugs. Thank god our secretary was overhearing my call and went to get front security to come take my phone, ask a bunch of official questions, and hang up on my behalf.

Another thing I wonder is whether being the social media generation, the people who turn our lives into quasi-professional, quasi-work-related “content,” are more susceptible to this stuff? A lot of our information is already public. We’re used to the notion of viewing ourselves with some detachment, as characters in stories, of our lives having some sort of narrative arc. I wonder if this subtly primes us to fall for scams.

It’s true—as far as I can tell, it’s pretty much ironclad—that major companies, banks, and government agencies won’t announce issues with your account or warrants for your arrest by phone call. It’s true that the scamming might stop if everybody remembered this and either refused or immediately hung up these calls, in every instance, all the time.

The reason that’s an insufficient answer is that we obviously don’t do that. Some problems simply have a public, collective dimension. If otherwise completely normal, competent people keep struggling with something, maybe there is an actual problem outside of their lack of willpower or judgment. “Victim beware” isn’t a legitimate approach to a criminal justice problem.

If you read a lot of the reactions to this piece, you can sense this thing I’ve noticed in a lot of other contexts, which goes something like, actually solving the problem would be bad, because it would relieve stupid people of the responsibility not to be stupid. This isn’t just uncharitable. It’s whistling past the graveyard. Blaming the victim is a defense mechanism. It’s a refusal to think, there but for the grace of God go I.

Here’s another comment on that story that puts it right:

I got an extremely similar call in September and despite being a first-class skeptic, I too immediately stopped thinking logically the second the caller activated my panic response (and btw, these people know exactly how to do that… they’re pros) and it took me a good 10 minutes on the phone with them to catch my breath again and start asking the kind of questions that eventually led them to hang up on me.

If you had told me before that call that I could be tricked into believing there was an iota of reality to such unreality, I would have laughed until I spontaneously combusted.

Now? Having experienced it myself, I completely understand how this happened to the author, and I’m truly sorry it did.

In some ways it feels like we’re seeing the decline of state capacity here—of the government to be able to identify a problem like this, and crush it. It’s also worth noting—for the folks who have implied the post-pandemic rise in disorder is due to police not doing their jobs, either because of George Floyd (if you’re on the far right) or to spite progressive prosecutors (if you’re on the far left)—that scamming is a white-collar crime, or at least not a blue-collar street crime. The answers are probably more at the corporate and institutional level than at the level of arresting and aggressively prosecuting individual scammers, though they deserve that.

More broadly, this is one of those things that I think people file under the term “inflation.” This sense that there’s an increasing precarity, vulnerability, and deterioration in the texture and quality of American life.

The feeling that we’re undergoing a rising tide of disorder is not just about carjackings or shoplifting or homelessness. It’s about things like this—the creeping feeling that the state is failing at a very elemental responsibility. And with AI exploding, these vile scams will only get more prolific and more sophisticated. This is bad, bad stuff. It approaches a dereliction of duty by the state, to ensure that people can go about their lives more or less unmolested.

We used to have a vibrant body of political activism called “consumer advocacy.” We fought tough political battles over things like warranty terms, the lemon law, automobile safety, and many others. Go back all the way to the food safety fights of the early 1900s. We take for granted just how much these boring, wonky things ensure a smoothness to everyday life and enhance trust and stability.

Consumer advocacy still exists—look at the revival of antitrust, the campaigns against junk fees and surprise billing, and the right-to-repair movement. But it is nowhere near as large a share of politics as it should be. It cuts across partisan lines, and it’s government engaging in one of its inescapable duties.

Scammers, like traitors, erode trust. They’ve helped make the phone call a suspect mode of communication. No matter how stupid some of us might be, no matter how much any particular scam’s success can be attributed to a mistake on the part of the mark, we deserve better than to let these criminals overrun our communication commons and loom so large in our lives.

Related Reading:

You Never Know How It Falls Apart

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 900 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Hoo boy. I've got a lot of thoughts on the subject, which I can hopefully organize well enough to be edifying:

1. As a 43-year-old financial professional, I think that people like me have a modest social obligation to engage with scammers. The young and elderly tend to be naive or cognitively declining, respectively, and people in other occupations don't always have an instinctive feel for what is and isn't a normal business transaction. I don't consider the obligation unlimited, obviously, but sometimes the cost/benefit is pretty good.

To give two specific examples: first, I'm the target of direct deposit scams (wherein the scammer impersonates an employee of a company and asks someone with access to that company's payroll to change their direct deposit information, and thus redirect the real employee's next paycheck). I have a quick reply to obtain the scammer's bank information, which I then forward to their financial institution with a request to freeze the account. All told, this takes less than 30 seconds of my time and forces the scammer to set up a new bank account.

Second, fake law enforcement callers can be kept on the phone for a surprisingly long time by confirming basic details like my address and phone number - those are effectively public records and there's no security risk in acknowledging them - and then asking for as much detail as possible about the supposed crime that I've committed. I have to stay on the phone too, of course, but that's less of a cost when I'm driving / sitting in an airport as opposed to productively working in my office.

2. /r/scams is a great resource, although sometimes the people there don't have compassion for a scam victim who is slow to acknowledge the existence of a scam.

3. US federal law enforcement superficially cares about the issue - for example, the FBI has a dedicated website for internet crime at https://www.ic3.gov/ - but they will never be able to engage with a scammer in real time or give timely feedback that the complaint filed with them was worth the time and effort it took to file. I think there's an opportunity for state attorneys general to make a name for themselves by taking on scammers; they obviously will have victims in their state who give them jurisdiction, and their offices are smaller and can be more nimble in their response.

3. Hearing Indian English is a major red flag that the person's calling to scam (or at best, to sell a legal-but-dubiously-valuable service), which is obviously unfortunate for the many law-abiding Indians. Jacobin had a great piece on this a few months ago: https://jacobin.com/2023/10/the-empire-calls-back

4. I'm hopeful that the antitrust revival leads to better service from Amazon and the like. Competitive businesses have a hard time getting away with things like you've cited, although I agree that there's been a decline in service quality everywhere in America over the past few years.

5. Last but not least: American scam victims might well be gullible, greedy, or dumb, but we need to think of them as *our* gullible, greedy, dumb family, neighbors, and countrymen, and deserving of our loyalty on that basis.

This piece does a great job of articulating a feeing I encountered at an airport this weekend.

My wife and I returned from our honeymoon in Costa Rica on Saturday. Along with (or perhaps because of) being an incredibly beautiful, sustainable country in every conceivable way, the population is almost jarringly friendly. We were running a bit late for our flight, and the agents immediately sensed that and escorted us to the front of all the airport queues. Nobody asked questions, nobody got angry that we were cutting, nobody gave us dirty looks. It was truly just people helping people, with the understanding that we would all get where we were going either way.

Landing in Fort Lauderdale was a dystopian hellscape. TSA agents screaming angrily at lines of tired, worried customers. Customers in the face of TSA agents screaming at them. Every employee we talked to gave us a different or unhelpful answer, or barely looked up from their phones. No compassion, no acknowledgement of our shared reality or desire to improve it.

I mused aloud in the passport line how everyone in this country seemed so miserable. Everyone around me (who had also just returned from Costa Rica) instantly agreed, and one insightful traveler noted that the TSA agents are reflecting the energy of the anxious crowd, but the crowd is mostly anxious because it feels like you are in it alone and nobody who is ostensibly there to help you cares to do so.

Apologies for the rambling post here, but you really hit on something I felt very acutely. It doesn't have to be this way; in fact it would be easier and more efficient if it were not.