Over the past twenty years, Henrico has prioritized the construction and renovation of libraries, a strategy you could call “library-oriented development.” Similar in concept to the more common transit-oriented development, this land-use pattern has helped Henrico create a strong and unique sense of community and identity, not just existing as a bedroom community for the city of Richmond. Today, the county has a total of nine libraries—equal to the number of public high schools.

Libbie Mill Library is one of the newer libraries, built in 2014. It sits in the middle of a mixed-use development, as the parcel it sits on was donated to the county government by the Libbie Mill Midtown developers.

Even though most of the space in the development is dedicated to car-centric design, with expansive surface parking lots, the relatively dense housing and ample sidewalks make walking and biking to the library easy for Libbie Mill residents.

Henrico County borders Richmond, and driving through it, it feels pretty much like Sprawlville, USA. But this is interesting, and despite the lack of much urban form, there’s more of urbanism here than meets the eye.

It’s not perfect, but this is more than you get in most places like this. Read the whole thing.

A recently proposed luxury Airbnb building along Front Street brought to you from Vich Properties indicates investors are still optimistic that visitors are eager to stay in the neighborhood, even if it means putting up with a little bit of noise.

A zoning permit issued last week reveals plans for a three story building on a currently vacant lot at 336 N. Front Street, currently filled with overgrown vegetation.

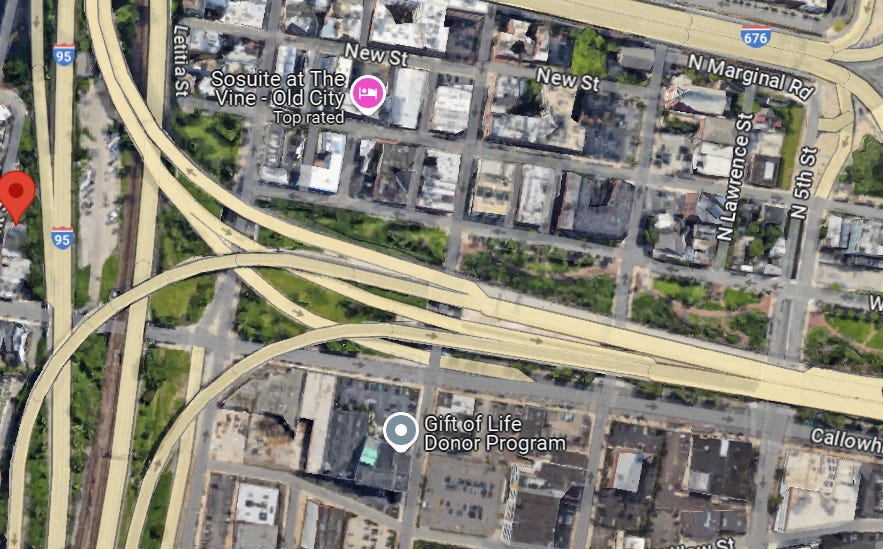

This lot, in the Old City historic district, sits between the expressway and a billboard, right at the red marker:

Trubman asks a thought-provoking question here:

This site evokes some interesting questions about the purpose of the Old City Historic District: for a neighborhood that was absolutely devastated to make room for highways and arterial roads, does curtailing infill development like this project do more to preserve the legacy of late 20th century urban renewal than colonial era charm? What role should a historic commission have in dictating what can and cannot be built next to a giant highway billboard?

Take a look at this: you can still make out the obliterated city blocks where the highway ran through:

One of the contradictions/frustrations/whatever you want to call it of urbanism is the fact that when it comes to car infrastructure, it mostly just happens, but when it comes to housing or remediating the damage done to cities, everything is subjected to thick process and litigation. One reason for that, ironically, is that urban renewal made us averse to just do things quickly. There are other reasons, of course. But some things should be done quickly.

Amazon Has Transformed the Geography of Wealth and Power, The Atlantic, Vauhini Vara, March 2021

MacGillis, a reporter at ProPublica and the author of a Mitch McConnell biography titled The Cynic, was one of the first journalists to begin documenting the socioeconomic upheaval that helped shift the rural Rust Belt from blue to red and put Donald Trump in the White House. In Fulfillment, he is less concerned with the much-discussed electoral implications than with the tech-era upheaval itself. The superficially equalizing promise that customers everywhere can enjoy unprecedented convenience with a mere click has intensified the differences in the choices available to the rich and the poor. MacGillis describes how, while rich corporations and their top employees have settled in a small number of wealthy coastal cities, the rest of the American landscape has been leached of opportunities.

This—this sort of left-ish economic populism—is good stuff. It’s a thing we’re missing in our politics and punditry, I think, along with old-school Ralph Nader-style consumer advocacy. It isn’t anti-business. It’s something else.

This is also a really important point:

The sense of entitlement on display in the company’s search for a second headquarters site is breathtaking. Local officials across hard-knock America prostrate themselves for a chance to host it. In the end, Amazon chooses the suburbs of the nation’s capital—already one of the wealthiest areas in the country—and walks away having amassed a great deal of useful regional data provided by eager bidders who probably never stood a chance.

Give it a read.

Life After “Calvin and Hobbes”, The New Yorker, Rivka Galchen, October 23, 2023

In 2014, he gave an extensive and chatty interview to Jenny Robb, the curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, on the occasion of his second show there. Robb asked if he was surprised that his strip was still so popular. “It seems the less I have to do with it, the higher the strip’s reputation gets!” he said. In the interview, he comes across as levelheaded, not egotistical, not very pleased with electronic devices, the Internet, the diminished size of cartoons—and also quietly intense, like the dad figure in the strip, who enthusiastically sets out on a bike ride through heavy snow. As a college student at Kenyon, Watterson spent much of a school year painting his dorm-room ceiling like that of the Sistine Chapel, and then, at the end of the year, painted it back dorm-room drab.

This is a long piece, with a lot of Calvin and Hobbes references, and it’s wonderful but a bit thematic. Give it a read.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

From Vauhini Vara:

"Amazon’s disproportionate ability to further enrich and empower already thriving places and workers is glaring." <br/>

"MacGillis explores most intimately the ebbing of human fulfillment that has accompanied Amazon’s promise of high-speed customer service."<br/>

The imperative of "high-speed customer service" for an online retailer is ironic and counterintuitive. Amazon and other online retailers aim to deliver goods faster even while they travel farther distances compared to brick-and-mortar retailers. But brick-and-mortar retailers in sprawl environments are not always convenient, even with access to a car. Essentially, sprawl retailers are the penultimate nodes for goods in their transportation to customers, in what I call "incomplete supply chains." Instead of smaller, better distributed stores, retailers consolidate large stocks in large poorly, distributed store, setting up their own customers to solve their "last-mile" problem through the donation of labor and capital equipment. Why should a customer donate their labor and equipment doing the pickups when Amazon will deliver to your front stoop? <br/>

The sprawl mitigation benefit of online retail is compelling, but the disconnection between the customers and the people who serve them makes service workers easier to ignore.

Still trying to figure out what a purpose-built AirBnB is. A house? A hotel? An all-suite hotel?