One of our favorite places to visit for a long weekend is Virginia Beach. It seems calmer, quieter, and a little classier than the big beach towns that fill up with college students partying. (It’s getting harder for me to remember when I was one.) But it also isn’t entirely commercialized, and I’ve always gotten a sense of the civic from this small beachfront city.

It feels, to use that hackneyed phrase, like a “real place.” There are these little museums right along the boardwalk, on what must be very valuable property. A museum for rescue workers and firefighters, and a museum on duck decoys and waterfowl and hunting. There are memorials and statues along the boardwalk. There’s a dedicated bike path and plenty of room to walk, either on the main boardwalk or a street or the beach itself. I always get the sense that care and deliberation has gone into this place.

Department of Museums!

It even won a public space award:

It has that hard-to-describe feeling of being dense with delight. Here’s an article that sort of captures it in a totally different context: it’s about how Nintendo takes a certain Japanese garden design aesthetic as inspiration for its in-game worlds. I think what urbanists call “fine grain” is sort of describing this, but that term isn’t really intuitive. Strong Towns coined the more understandable term “delight per acre.”

This delight is despite the aging oceanfront hotels and rental buildings, but even they’ve been maintained pretty well. I took this picture, telling my wife, “I’ll use this for my newsletter if I ever write about ugly architecture,” and she said I could do much worse than this. I agree.

You’ll get some people complaining about petty crime and over-tourism here, but for the most part it’s quite safe and pleasant, and has more of a family-friendly vibe than some beach towns. It’s the kind of place I can imagine coming back with our kids one day and retracing our steps.

Maybe “real places” are simply places that contain every kind of person. Places that unselfconsciously accumulate layers of history and experience that in some sense everybody can share.

Well. Not everybody.

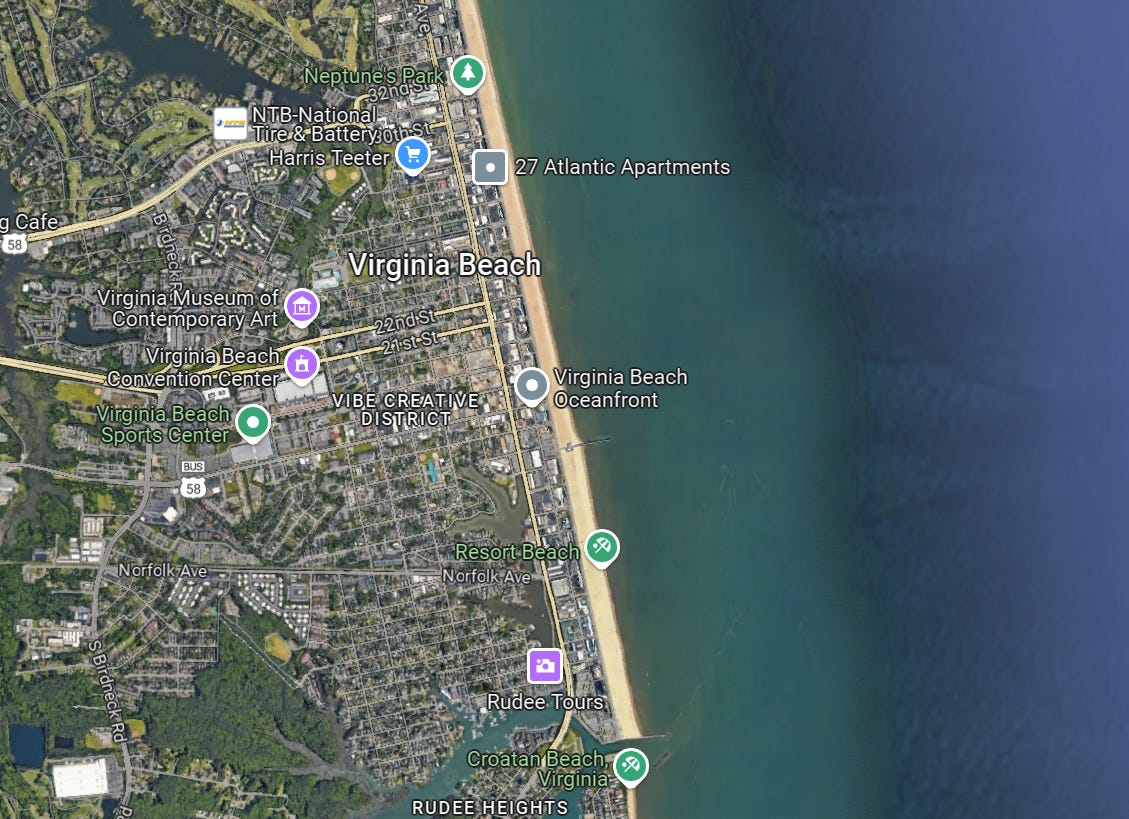

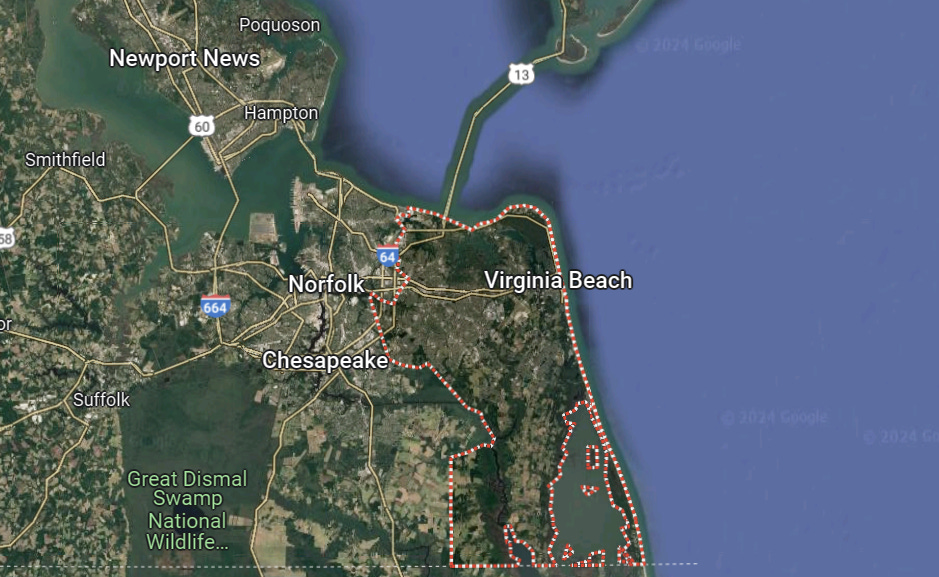

I called Virginia Beach “small” earlier because I’m referring to the numbered, gridded streets right along the water. But in fact, the city limits are much larger, spreading miles west and south, including a large amount of basically suburban development.

There’s the city city: the beachfront grid, the commercial strip behind the boardwalk and the mix of apartment buildings, motels, local stores, and little houses. That wonderful low-intensity urbanism of a larger town or smaller city, enough to engage your imagination but not enough to overwhelm you.

This is the core:

But here are the city limits:

That vast suburban and even natural, undeveloped expanse all around the core would, pretty much anywhere, be a distinct county.

It turns out, that used to be the case.

You can find competing explanations/narratives of what exactly motivated this, from barely mentioning it to concluding that Virginia Beach was founded on racism. But what happened is that the vast area around the Virginia Beach urban area, which had been a popular resort city as far back as the 1800s, used to be Princess Anne County, which dated back to the 1600s. (Virginia Beach, for most of its existence, was unincorporated. It incorporated in the 1950s, but that didn’t last long.)

Norfolk, a majority black city to the west, annexed some of Princess Anne County’s land in the midcentury period—around the same time as the civil rights movement and school integration were unfolding. Between the possibility of coming under the administration of a black city and having Norfolk children in the mostly white Princess Anne schools, the county and Virginia Beach city mutually agreed to merge, with the county essentially swallowing the city and largely taking over governance, but the city name being retained for the new locality. (It’s almost like one of those stock transactions where a new company buys an existing company in order to go public with no review.)

Here’s an interesting interview with a (white) Virginia Beach resident who grew up there during the time of the merger. It opens with this basic history:

For just over a decade, from 1952 to 1963, the city of Virginia Beach consisted of 2 square miles and just over 8,000 people (according to the 1960 US Census). In this interview Verna Marie talks about many of the people and places of the “old Virginia Beach,” including several schools and many local businesses, many of whom have since been replaced due to urbanization at the Oceanfront. Most of the non-Oceanfront area was part of what used to be the county. Princess Anne County consisted mostly of farmland, but was home to over 76,000 people in 1960. The neighboring city of Norfolk had a history of annexing land, that is incorporating land from a county into a city’s limits. After having some land annexed, Princess Anne County merged with the city of Virginia Beach, for fear of losing more land. Though the small city’s name stuck, the government of Princess Anne took over that of the former city, demoting most Virginia Beach officials within their same office.

Here’s a Reddit thread about Norfolk, which touches on all of this.

Back in 1948, passenger trolley service from Norfolk had ended. This was due in part to the reasons trolleys were being scrapped everywhere. As far as I can tell, the city of Norfolk got rid of the trolleys.

However, a proposal in recent years to create a new light rail connection from Norfolk to the Virginia Beach beachfront, supported by Norfolk, was voted down in a landslide by Virginia Beach voters.

You can probably see more than is there, but there’s something there.

This isn’t the most comfortable bit of historical trivia. But today Virginia Beach the old city, the suburbs, and the suburban parts of the other cities which border it, are all pretty fun places to explore and not at all bad places to live, as far as I can tell. The old urban cores in Hampton Roads are poorer and heavily black, and there’s simply less for a tourist to do in them. (Although I did go fishing once in Hampton, and the crowd was pretty evenly black and white, and trended older, too. I would describe the areas I drove through more as timeworn than rundown.)

Virginia Beach itself is only 60 percent white these days. The outer areas are no longer rural or agricultural. After the Northern Virginia agglomeration, Hampton Roads is the largest population center in Virginia; Richmond is third. And like other major metropolitan areas in the state, the region is actually quite diverse. Not just black and white; there are lots of immigrant communities here too. Latinos, but also Filipinos, Chinese, Vietnamese, Jamaicans.

For some reason, despite the region’s suburban sprawl being very typical and slightly dismal—lots of wide roads, 20-minute drives from any given place to any given place, lots of low-slung office parks and old, unrenovated strip plazas—I rather like it. It isn’t pleasant from the point of view of the architecture critic or the city snob. But it feels full.

There’s a lot of of culture here—lots of small businesses and restaurants, relatively smaller commercial spaces, fewer of the massive “power center” shopping centers mostly populated by chains. We’ve also found the best hand-pulled noodles and the best Sichuan food down here: better than anything we’ve had in Rockville, Maryland, which many people describe as D.C.’s true Chinatown these days.

One night, we brought an inexpensive dinner home to eat at our Airbnb’s pool deck, from a little pupuseria along one of the older commercial strips in Chesapeake. Every customer was Hispanic, as far as I could tell. I can imagine that this is basically a neighborhood, its aging suburban form masking something more pleasant and communitarian. (The cashier was very patient explaining the menu to me—they must get some gringos stopping in.)

These realities don’t cancel out the very real history of racism, which is not all in the past. But they’re big changes from 50 or 70 years ago. And they feel utterly normal.

At the beach, we walked past those little landmarks in the photos up at the top. We parked in a free public lot a few blocks away from the beachfront, in the “ViBe Creative District,” where we also had dinner at a neat little place where most of the seating was one long shared table. We then walked through a few city blocks, and past the edge of a major construction site, on the site of an iconic music venue and civic center, The Dome. It once hosted The Rolling Stones, but fell out of use and was demolished in 1994. The new site is a mixed-use development with, of all things, an artificial surf lagoon. Some might call that sort of thing a boondoggle. I’d like to think of it as a small city thinking big.

We walked along the beach, its friendly but energetic atmosphere—couples, kids, families, vendors selling noisy toys and light-up balloons out of carts, the breeze and the ocean mist—engaging and comforting, new and old every time.

At the end of the evening, as we walked back to that empty free parking lot a little too far from the beach, we stopped in surprise at seeing horses clomping along down the street, towards the beach. It took a second for us to see that it was police officers riding them, patrolling on horseback.

I confirmed with one of them, who waved at us, that this wasn’t some special event. “You guys actually patrol on horses?” I asked. Yep, one of them answered. It turns out the city’s police department has a mounted patrol unit. It’s the first time, in our several visits, that we caught any of them out.

It was the coolest thing, trying a quirky little local place for dinner, walking home from the beach, catching a sight of something unique. A little mini day in the city in such a small piece of geography. That’s neighborhood character. If only more places in America felt like this.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Horsey cops! That's a sign of soul. Most big cities had horse cops until WW2. Chicago still had them in the '60s.

The persistence of horses in route driving might also be a measurement. Spokane had mail chariots until 1948, and Toronto had streamlined milk wagons in the '50s. The horse was an autonomous vehicle, letting the milkman focus on sorting and billing. The horse knew the route and the stops and some of the people.

Mail chariots:

http://polistrasmill.blogspot.com/2015/04/finally-picture-of-chariot.html

Streamlined milk wagons:

http://polistrasmill.blogspot.com/2010/08/future-seen-from-past.html

I worked up in Surry (across the James River from Williamsburg for those that can’t place a town of 250 on a map) for a summer and loved headed down to Virginia Beach. I somehow messed up the directions of “just head down 264 until it ends” and ended up in Sandbridge which was not a bad thing by any stretch!