A few weeks ago at The Bulwark, I wrote once again about stoves (first time here).

For those of you who didn’t see my previous piece and follow-up here: I used to own a gas stove, and I loved it. I thought electric stoves were unusable junk, and that I never would or could cook with electric. Our new house came with a pretty good glass-top electric model, however, and I discovered that it is, in fact, usable. I like it a lot, and intend to keep it in service for as long as I can. When I eventually replace it, I may look into induction.

I think the growing body of research pointing to negative health effects from gas stoves is probably basically legitimate and real, but I have not seen a good explanation of how much risk we’re really talking about (relative to a wood-burning fireplace, or living near a major road, or smoking, or having home heating oil for heat, etc.)

I thought the suggestion that sparked all this, by an agency commissioner that a gas stove ban might be on the table, was going way too far, and it is not true that conservatives invented the gas stove issue. Going after gas stoves has been a priority for some progressives for years. As I wrote: I know, because I responded to an anti-gas-stove piece in Mother Jones two years ago!

But in this latest piece I used the gas stove kerfuffle to try to think more deeply about what, exactly, was going on. And I ended up talking about risk, and how we determine which risks we find acceptable or salutary, and which ones intolerable.

I’m not the only one who found this to be a useful discussion; Bonnie Kristian, at her Substack, excerpted it too, and had further thoughts about it. Her remarks are interesting:

Over at The Bulwark, Addison Del Mastro, with whom I worked a bit at The Week, has perhaps the sole unique angle on January’s gas stoves kerfuffle—and that’s because it’s mostly not about stoves at all. As his headline says, it’s about “What the weird clash over gas stoves tells us about conservatives and risk.”

I’ve written on different risk assessments a handful of times, at least once at The Week (“Why pandemic parenting is harder than the data suggests it should be”) and more recently at Reason (“Left and right are living in different realities”)—maybe enough that I’m straining the bounds of this item category. But I’m coming back to the topic because I find it fascinating. (And, eh, my Substack, my call.)

Risk assessment is something we often do subconsciously and usually notice, if we notice if it at all, at the individual level—you know: My husband is so cautious; he takes forever to make a decision with any big purchase or Yeah, she just moved there without knowing anyone! I could never. Even then, we don’t necessarily make the leap to thinking about risk assessment on a societal scale or as influenced by politics or religion or other factors beyond individual personality.

And from my piece:

Cooking entails risk; if you do it wrong, you could burn yourself or get food poisoning. Yet driving to the restaurant also entails risk; you could have a car accident. Gas stoves entail some health risks, yet if you find a gas stove to be the only usable type, perhaps your overall health will be improved by cooking at home with gas versus eating more unhealthy takeout food. Etc., etc.: Everything involves risks, and so acknowledging and weighing them is unavoidable.

But those conservatives who speak in high-minded abstractions seem to be driving at something more than this mundane observation. One often gets the sense that they believe that risk is not just inevitable, but somehow good; that is it invigorating; and that attempting to eliminate risk is not merely futile but cowardly and enervating. One wonders, in fact, if they can tell the difference between risks inherent in the business of living and risks that arise from specific and remediable actions or inactions.

But once again, slipping into culture war mode means that none of this can be weighed and considered. And so we’re faced with the odd sight of people who would do anything for their children, like move to the safest possible neighborhood with the best possible schools, scoffing at the idea that keeping a gun in the house, or running a gas stove, could possibly present any risk at all. Or if it does, risk is part of life.

Really, that middle paragraph is the point. I’ve repeatedly noticed—about cars, about COVID, about stoves—this tendency to almost glorify risk, as though ensuring our health and safety were some kind of illegitimate endeavor. As if the desire to be safe is the desire to be ruled, to give up the exhilaration and daring of self-government. As if being a good American requires you to put yourself in danger on a regular basis. Those who trade liberty for security deserve neither. Etc., etc.

I am probably exaggerating a little bit. But the pandemic really laid bare for me that a lot of people think this way, whether they would put it quite in these terms or not (and believe me, some of them do.)

About a year ago, I wrote a long piece really sharply criticizing conservatives who basically shrugged at the pandemic, or worse, painted public health as cowardly, or even worse, cloaked this misanthropy in Christianity. I made a lot of the same points there that I did in this piece about stoves. And it’s interesting how similarly the rhetoric and culture war played out.

The other thing I noticed was the fringe of conservative responses that went something like, “They’re doing this so they can cut your power off.” The gas stove, for some, symbolizes self-sufficiency (only, tenuously, if you have a huge on-site propane tank that you own.) I guess because of environmentalism, a certain segment of the right now views electricity itself as somehow vaguely suspect. This is very different from griping that environmental regulations have made consumer products worse (CFLs; water-efficient dishwashers, toilets, and showerheads; etc. None of these much interest me, but I get it. It’s an actual, practical, observable complaint.)

But that other stuff—the fear that every regulatory or health action is part of a plot to turn Americans into subjects of the state? Like so much else, it’s just a fantasy. It’s reminiscent of the notion that driving a massive pickup truck makes you working class, but riding a bike makes you elitist. That enjoying a nice coffee or working remotely makes you a member of some feckless “latte-sipping laptop class.” These absurdities are repeated so often that they begin to feel as though they have something to them.

You know that little story, when someone comes across a barn full of manure? One guy says “This barn is full of manure!”, while another guy says, “There must be a pony in there somewhere.” When I see this kind of overheated discussion over stoves, housing, zoning, what have you—I think, there must be a real issue in there somewhere.

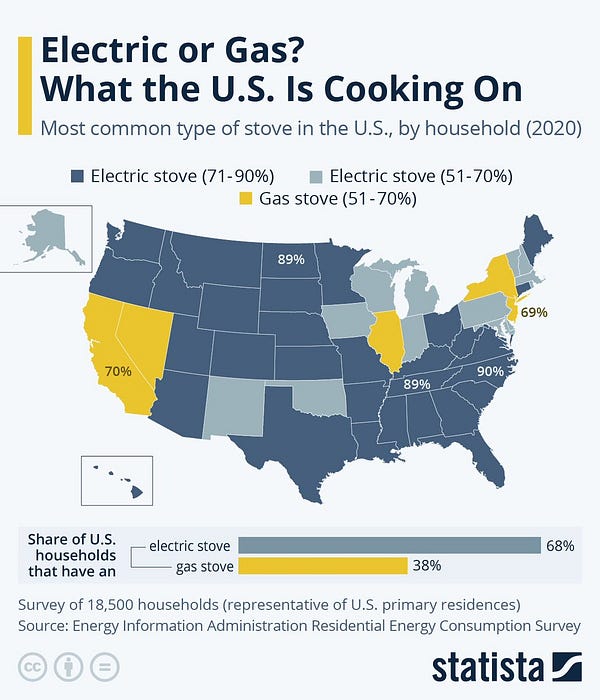

There’s one more little twist in all this, though: gas stoves, unlike pickup trucks or zoning fights, or showerheads or dishwashers for that matter, are highly regional. Take a look at this:

Now you can see the freezing Upper Midwest has a considerable amount of gas infrastructure, which has the dual purpose of heating and enabling cooking during power outages, if those gas homes also have gas stoves. (Some homes are gas-connected but still have electric cooking.)

But most of the country mostly doesn’t use gas, and the distribution of gas infrastructure has no overlap with modern partisan divides. So that’s interesting, and it probably means this simply won’t be that powerful of a political issue.

Alright, one more thing. The most convincing argument for gas cooking, to me, is not about the performance of the stove per se, but rather that you can still cook and boil water without power. That will be needed rarely, but could be very important, conceivably. I’ve done it myself, in our old place, during an unlikely March blizzard that knocked our power out for almost 48 hours. You just turn on the gas and light it with a match. (The ignition is generally electric.) Be careful, and you’ve got yourself a stove.

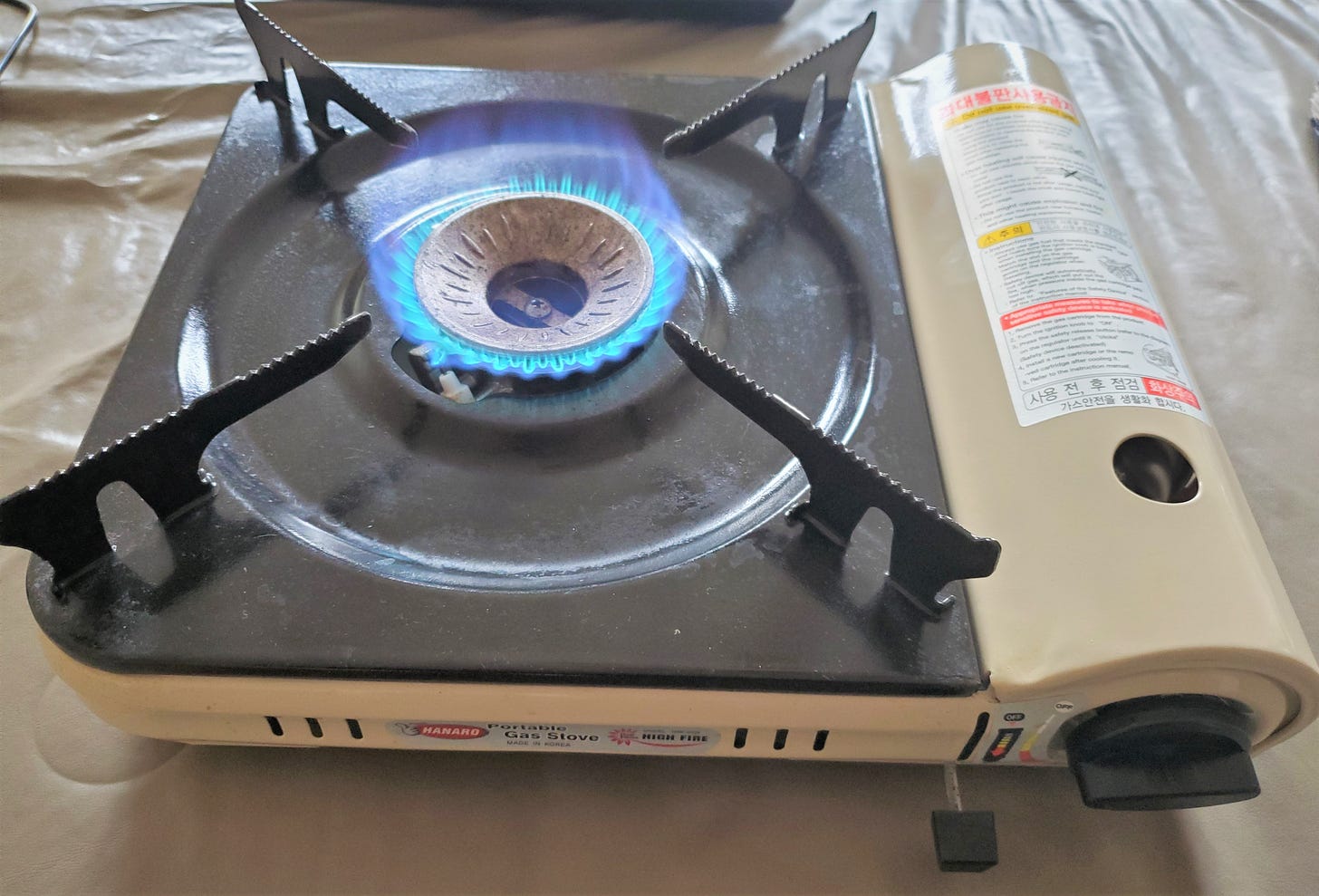

So I was a bit concerned that I didn’t have that backup in our new place. And then I remembered I have this:

It’s a portable little gas stove that uses canisters of butane. The stoves are $30-$40; the canisters are $2 or $3, and burn for maybe an hour or more.

You may have seen these at an outdoor or camping store. But this one is from Korea, and they’re typically used for Korean barbecue or hotpot (you can buy different plates and implements meant to sit on one of these.)

If you want the ability to cook in a power outage, grab one of these online or at an Asian supermarket if you have one (H-Mart, a Korean chain, is the best bet.) It’s interesting how these are not so common in “American” stores. They’re quite useful (and can be used outside, too!)

And now, I think I’m done with stoves.

Related Reading:

Apartments, Ownership, and Responsibility

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 500 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Politics of Everything (https://newrepublic.com/article/170246/fiery-gas-stove-wars) had a good ep last week on gas stoves, really dug into how it's become a cultural touchstone. Also did a really good job hammering home the health problems associated with it that have been known for literally decades and made some comparisons (perhaps unfair, it's very preliminary) to Big Tobacco.

I think it’s relevant to point out in regards to “But those conservatives who speak in high-minded abstractions seem to be driving at something more than this mundane observation. One often gets the sense that they believe that risk is not just inevitable, but somehow good; that is it invigorating; and that attempting to eliminate risk is not merely futile but cowardly and enervating.” that that is not really the case in terms of all risk management, but more specifically in the area of legislation (forcibly making something illegal by way of legislation). The argument is how to weigh proportionality. I don’t believe conservatives are against risk management. Making something illegal actually curtails risk management at the individual level. It’s also not that risk is necessarily invigorating, but that there is a cost in prohibiting something, on many possible levels (firstly personal freedom), that needs to be weighed against the positive aspects of legislating.