The other day, I changed the toilet paper at my favorite coffee shop.

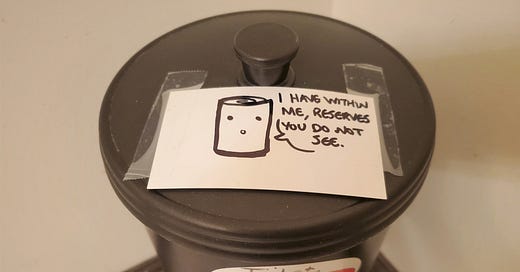

It was a quick, obvious, almost amusing thing to do, given the toilet paper storage container they have:

It’s always a little delight to climb up to this place’s second-floor seating area, which overlooks the first level.

There’s a little utility closet up there with a “door” made of burlap coffee sacks. There’s artwork and various pop-culture memorabilia all over the walls. The way up to this loft area is a staircase that looks like it’s from a house.

The bathroom is also outfitted like a residential bathroom, rather than a commercial one. This place is small. But it feels big and homey at the same time. The upstairs has this lovely nook-and-cranny feel.

Some of this is an aesthetic. But it goes deeper than that. Its quirkiness and granularity is, I think, a product of being a small, independent business. It’s in an industrial/commercial park (near a brewery, catering place, gym, and other businesses that are here either for zoning reasons or for cheap rent.) Chains want conformity and uniformity; they don’t want amusing handwritten signs on the toilet paper storage container, or nooks and crannies, or odd locations. The predictability of the chain, and the texture and interest of the independent business, are not just different; they’re like acidic and alkaline. You can’t have both.

What’s interesting to me is how the small business invites you to be part of it. You’d feel like a bit of a chump changing the toilet paper at Starbucks (if you could find the toilet paper). A faceless “they” is supposed to do that. The remoteness of the chain business encourages detached complaining over a feeling that the store and its customers and its employees are all part of something shared, something that exists because of all of us.

Sometimes, conservatives make a point like this about government. Government is big, remote, and faceless. It doesn’t form relationships, it just dispenses money. It encourages a lack of appreciation and gratitude, and a kind of passivity.

To the extent that this critique is true, it is really equally true of the bigness and remoteness of suburbia and the large-scale, car-oriented chain retail that goes hand in hand with it.

We are right to lament the loss of community institutions, small businesses, and neighborhoods where everyone knew each other and looked out for each other. But the physical context of most of American life today works against all of those things.

Now, a lot of these trends are more recent than suburbia itself, and many researchers are skeptical of this whole line of analysis. But I wonder if these trends did not appear earlier only because it was not until the 1970s or 1980s that we began to have a critical mass of multigenerational suburban families: that is, people who did not move from “the city” and bring their urban habits and outlooks, but who were born in the suburbs—which, over the decades, became increasingly less traditionally urban in their scale and form.

I do not think land use explains everything. But it is the context of everything. When we bulldozed cities, built monotonous, impersonal suburbs, and oriented commerce and life around the car, we unbuilt the physical context that helped us to form community. And modern zoning prohibits much of the sort of urban fabric that underlaid this more communitarian version of our country.

At the time it seemed like a good idea.

So often, we talk about these things—virtue, responsibility, work ethic, forming community—like they happen in a vacuum, unaffected by their context and surroundings. As if it would almost be wrong to make these things easier, because that would deny or deprive people of agency. On one end of this argument is the idea that humans are lab rats, and that human behavior is deterministic. But on the other end is the notion that human behavior exists independently of any context or outside forces at all. I think it is fundamentally conservative to acknowledge our weaknesses, our susceptibilities, our responsiveness to incentives.

To go back to my little anecdote: replacing the toilet paper is a considerate thing to do, all things being equal. But one approach to doing business makes it a more pleasant and natural task. So we should do and build more of that.

Related Reading:

Fifty Million Private Realms Might Be Wrong

A Different Take on Suburban Parking Lots

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive: over 600 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

I think you'd like digging in on the North East Development Cooperative: https://www.neic.coop/

Cool story, cool people, and a tested model to help local businesses succeed (that should be replicated elsewhere!).

Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community

2000, Book by Robert D. Putnam