A Tale of Two Highways

Central New Jersey showcases two very different kinds of linear development

My latest piece for Strong Towns is an illustrated road trip down two highways crossing central New Jersey on the way into New York City: U.S. 22 and NJ 28.

The development along 28 is small to medium in scale and fine-grained, and the road itself is no more than two lanes at many stretches. Along 22, things are larger and more spread out, with a handful of mid-century roadside buildings still intact. The giant Channel Lumber man no longer lights up 22, and a small amusement park, first opened in the 1940s, recently gave up the ghost and became a modern apartment complex. Some modern apartment buildings are going up amid smaller, older neighbors along 28. Bits and pieces of these two landscapes come and go and get remade, but nothing in the last 60-odd years has really changed their fundamental characters.

What’s more, highways 22 and 28 run parallel and very close to each other, at times less than a mile apart north–south. Within basically the same place, they’re two incredibly contrasting corridors. Of course, many places have a traditional core with car-oriented development along the edges. But what’s interesting and less common about the contrast here is that these are both long, linear places, and so traveling both of them allows a sustained view of two different development approaches.

Now, they’re not that different—Route 28 isn’t exactly fine European urbanism. Both corridors have a lot of suburban DNA. But the Route 28 corridor is home to a lot of old small towns and cities, and it serves as their Main Street. In other words, there was plenty of stuff there before the explosion of suburbia, and the later development retained some of that old urban DNA.

Route 22, on the other hand, was a U.S. Highway that started out pretty sparse and slowly got filled in with car-oriented development. One accommodates cars, and one is completely designed around the car. The fact that they’re not completely different patterns actually underscores how fundamentally the dominance of the car has changed them.

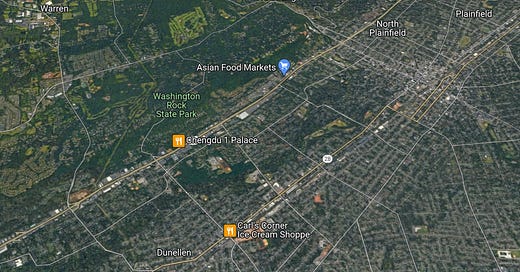

I wanted to share a few more images. I’ll start with an aerial view of the two highways themselves, running parallel, towards the top right of the image. Look at the difference in the development pattern between the area north of 22 and south of it along 28. (22 is where the Chinese restaurant is.)

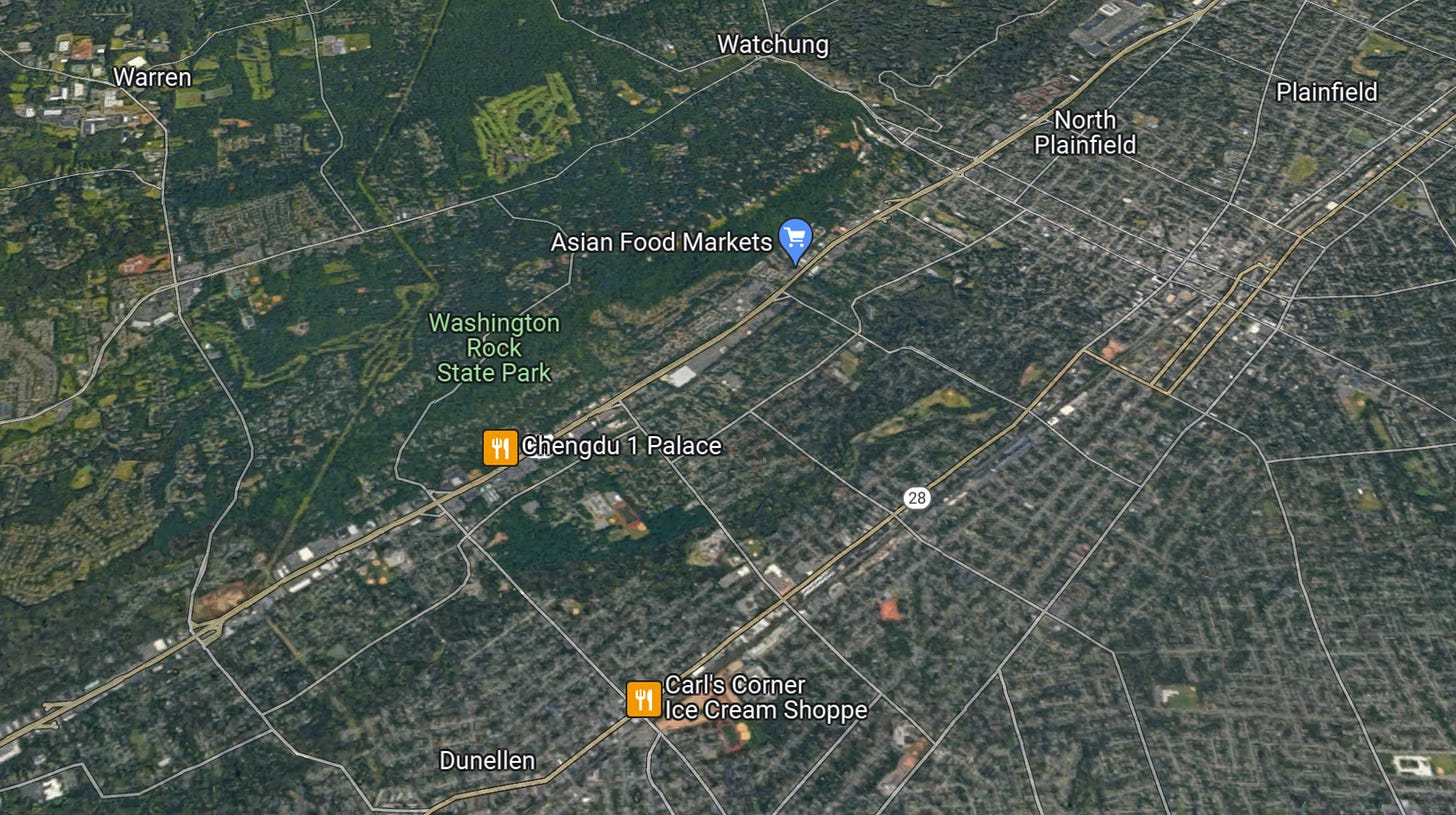

Next, I’d like to show you this. This is the latest of a series of ship-shaped buildings (the first was a nightclub) that has sat on this lot on Route 22 in Union, New Jersey for decades. PC Richard is a regional electronics and appliance store. It’s kitschy, but it sure is cool to drive past.

Of this segment of 22, I wrote:

I haven’t even gotten to the stretch where 22’s eastbound and westbound lanes split apart and surround a narrow strip of land with stores on each side. This is where Union, New Jersey’s, famous ship-shaped building resides, and if asphalt were water, it would sail away. Pictures cannot do that stretch of highway justice.

U.S. 1 in Laurel, Maryland does this too, but it’s fairly uncommon. Here’s what it looks like. First, from the air (the ship-shaped building is right in the middle):

And from the ground, viewed from the middle segment:

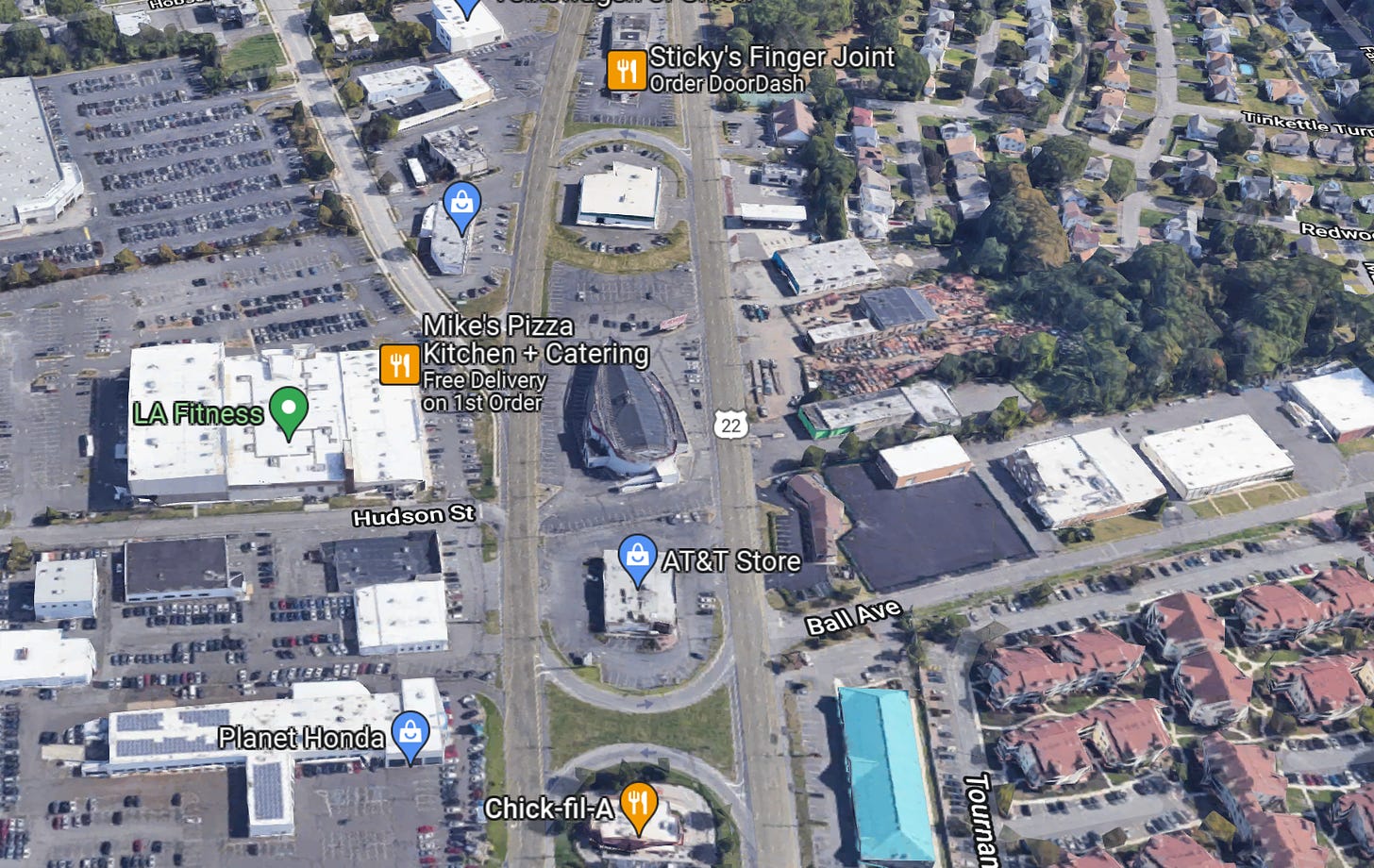

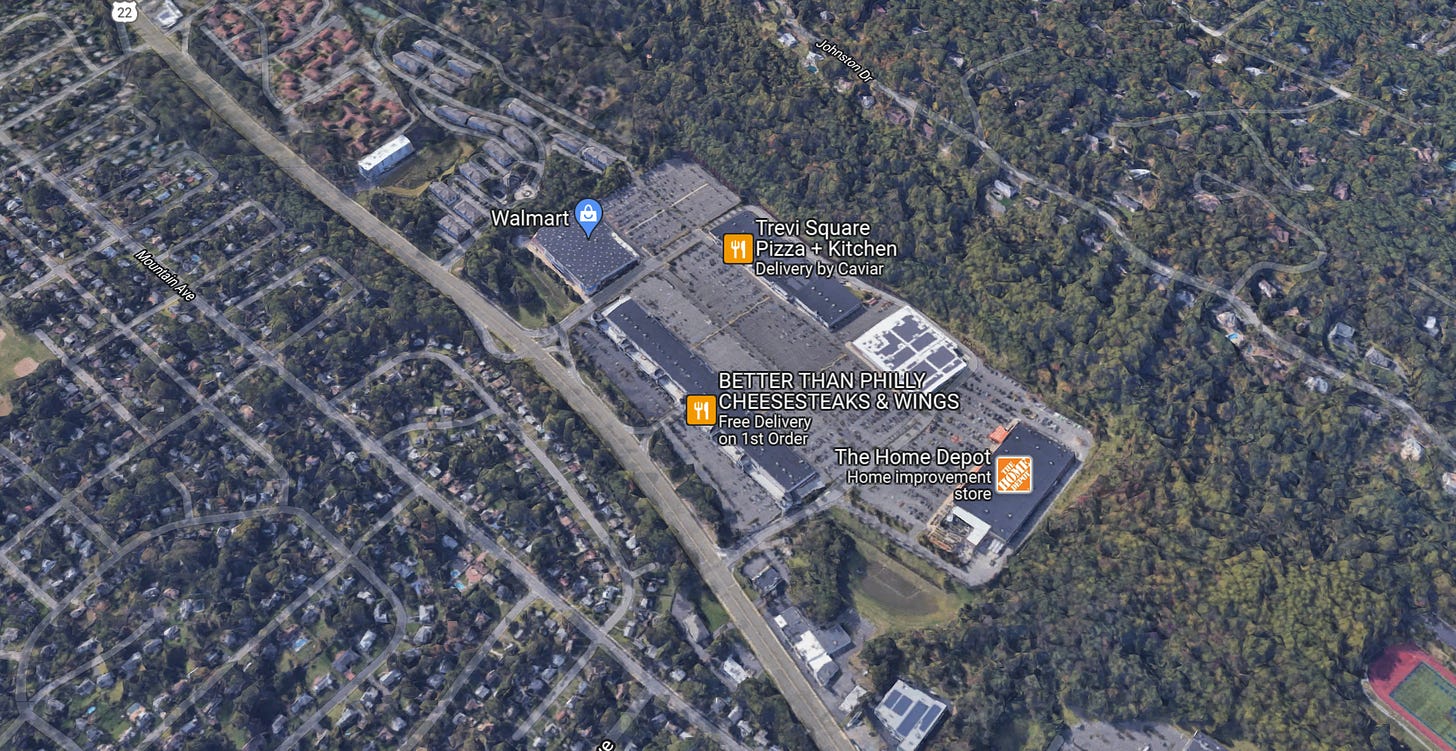

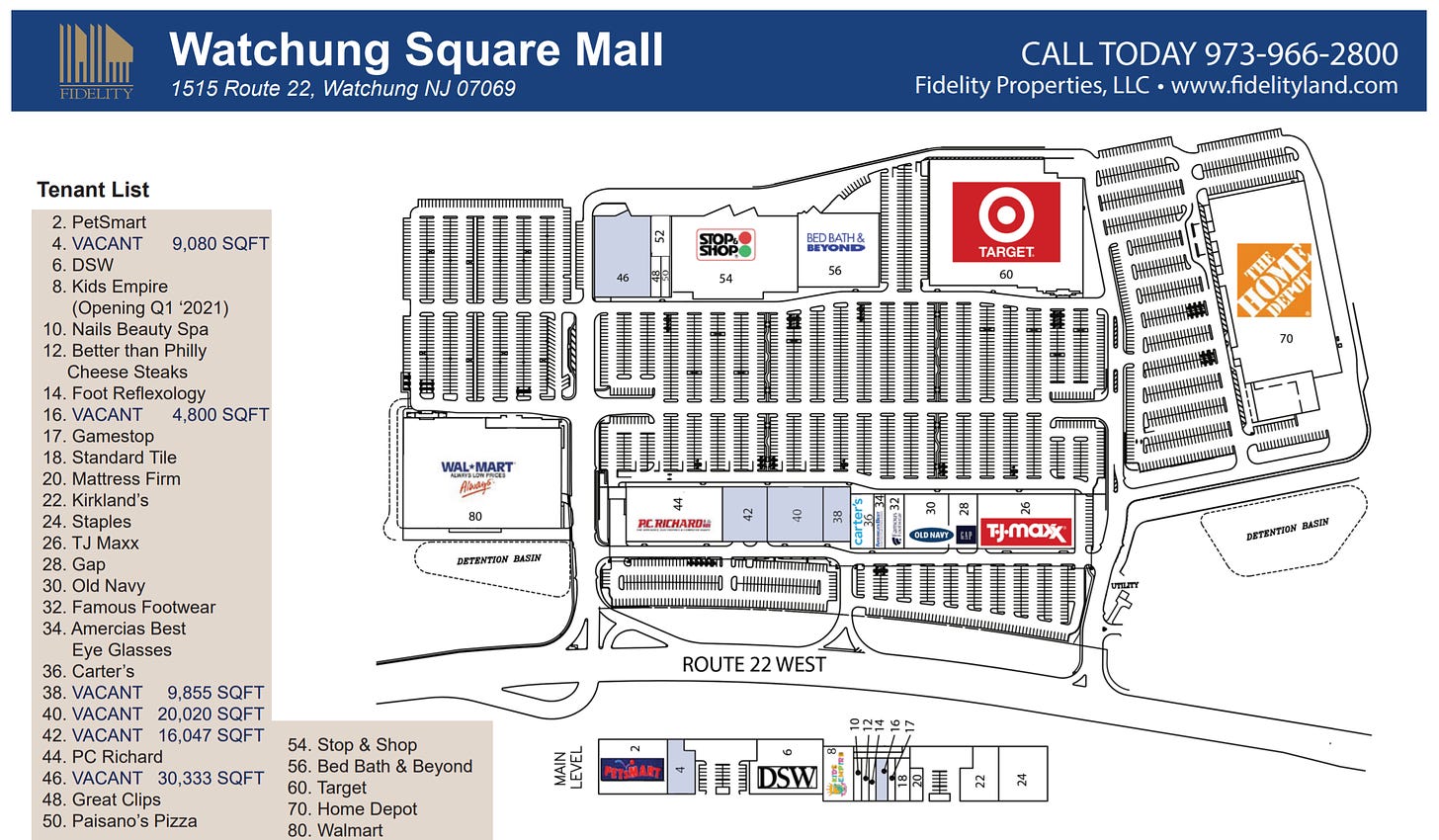

Route 22 is also home to this massive double-decker “power center” strip plaza, in Watchung. It boasts a bunch of small stores plus a whole bunch of big-boxes—both a Walmart and a Target. There’s a big retaining wall behind it, because it’s basically carved out of a slope. You have to drive up an inclined road to get to the larger second story. Shopping here, you certainly notice how big the parking lot is, but it doesn’t really register until you see it like this. The scale of this—and the scale of the various inputs and outputs that keep it going—are just massive.

And here is a map from the property owner’s leasing information.

A couple of photos from the ground, which I took. Here’s the retaining wall, behind the Home Depot. The bolts in it are as large as my hand!

And here’s a view of the parking lot:

As I noted in the original piece, that sprawly development north of 22 is more expensive and prized, while the more traditional development south of 22 is often referred to as the “bad” side (read CityData threads). However, the old towns along 28, whose grids radiate up to that southern edge of 22, are seeing new investment, and that perception may not remain true.

I’d also like to revisit a point I made in the piece, about which a whole lot more could be written (and probably will be!)

The trade areas of these large stores and shopping centers are meant to be large, meaning that while they certainly serve locals, they are not neighborhood businesses; the parking requirements are meant to be overly generous; and the highway itself is designed for fast driving. This is not a scale or a built environment that is particularly conducive to thriving small businesses or close-knit communities.

My question is how deep this goes. How much do economic trends towards bigness and centralization have to do with car-oriented land use, either as a cause or an effect? And to what extent are small towns and classic urbanism generally a sort of epiphenomenon of an economy that no longer exists? I think this is the real meaning of “human-scaled.” I’d like to revisit this.

Finally, I’d like to show you a couple of streets in Plainfield, a small city along Route 28. These are vacant (or perhaps minimally used) warehouses right along 28.

Perhaps the newer areas north of 22 are considered “better” because they don’t have artifacts like this. But that just kind of makes the point. Our attitude in America seems to be to build places, and when they start to get old, to move on and build new ones. That’s the problem.

What’s striking here is that barely a mile separates these two long linear places. This isn’t a question of inner suburbs being left for outer suburbs. For all intents and purposes it’s the same chunk of land with the same distance from surrounding jobs. And yet the towns with that older, more human-scale development, and with train stations that take you into New York City, for a long time were allowed to fall into relative disrepair. To be viewed as lesser, even though they were right there, built out in a lovely manner and home to tens of thousands of people.

Newer isn’t always better, and while I kind of like the ship parked out in its asphalt ocean, I do wish that more of our energy had been directed towards maintaining and building up places we already had. It’s not too late.

Related Reading:

What If Suburbia Still Looked Like This?

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive of nearly 300 posts and growing. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!