A Piece of New Jersey We'll Never Build Again

Thoughts on preservation, memory, and ordinary, fleeting things

One of the first articles I ever published, back in 2017, was a lament/appreciation for mid-century suburban commercial architecture. I’ve also touched on the decline of brick-and-mortar retail in rural areas. A now-vacant plot of land near my hometown in New Jersey highlights both. Here’s the Street View of the site:

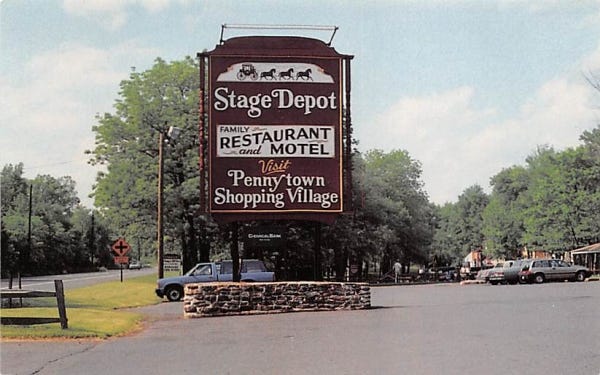

Situated among farm fields, along a lonely stretch of New Jersey’s Route 31 in Hopewell Township, it was once a quaint shopping center called Pennytown, designed to resemble a village. There used to be a bar and grill with ’70s wood shingles, a motel styled after a stagecoach house, a series of small shops including a local bank, a coffee shop, a quilt store, and a petting zoo with a pond, and, on the next lot over, a bowling alley. (Some folks on a bowling-focused web forum recall it; Internet forums are actually one of the best ways to piece together the physical history of a place.) Here’s what the restaurant looked like (from an old Mapquest page!)

One of the only online images of the motel (actually, I don’t even think that is that motel!) is this thumbnail from a Trivago ghost listing. It’s interesting how little can remain of something like this, and how quickly it can vanish.

The pond at the old petting zoo is all dried up, but a little wooden house for ducks is still visible through the underbrush—or at least it was the last time I drove by. The property had been slated for redevelopment since 2008. With a final assist from the Great Recession, Pennytown slowly closed down over the years, with some of the shops, then the zoo, then the motel, and finally the restaurant shuttering. The decline was complete by 2010, and by 2011, everything on the lot had been completely demolished.

This was not an ugly bit of suburban kitsch along a cluttered commercial strip. It was, at least when first built, one of the few pieces of commercial development for miles around. It was a little landmark that provided local color. It was also a place where one could purchase a fairly wide variety of goods from a number of small business owners. While many clogged suburban arterials could use less roadside development, many rural areas could actually use more. Pennytown, in some ways, was scaled to its small community and lightly developed rural environment. It almost resembled, or could have resembled with some incremental tweaks, a smaller version of the now-popular “town center” style of development. Here’s an old postcard:

I have a soft spot for stuff like this. Part of it is that I grew up visiting and shopping at these types of places. Not too far away is the similar Peddler’s Village in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and the now mismanaged and largely vacant, but once quaint and fun, Turntable Junction in Flemington.

Of course, it isn’t possible to mandate that such places survive, because they evidently aren’t profitable enough to make it as private businesses. And very little along the American roadside has the notoriety or historical value to deserve physical preservation in the face of changing economic circumstances, land use patterns, and population pressure. Pennytown is a very long way from Monticello.

It’s okay to mourn these things, but it’s not okay to turn that nostalgia into an ideology that seeks to encase places in regulatory amber and insist they look exactly like they did in 1950. If you think I’m exaggerating, just take a look at this flamboyantly NIMBY post at the Annandale, Virginia Chamber of Commerce, which laments, in an apocalyptic tone, the demolition of an aging commercial structure most recently housing a hamburger restaurant.

The sad reality is that many such businesses likely have no future. They may provide a secure living to their owners, but they are not always profitable or glamorous enough to pass on to children, who may not be interested in staying in their hometown and managing a little shop. Selling is the other option, but few buyers will want the existing business itself. Just down the road from the Pennytown site is a little family-owned eatery called Orlando’s. It will be sold one day, when its owners retire or exit the restaurant business. And it will most likely not be a local landmark to its next owner, but a chunk of highway-adjacent real estate zoned for a restaurant.

I find it comforting and calming that this plain building has stood there, unchanged, for as a long as I can remember looking out the back window of the car. I like the feeling of visiting home and having a sort of physical record of my childhood to spark memories.

Yet I often wonder what the people who built these buildings and started these businesses would think of suburban NIMBYism. Most likely, they’d be surprised their buildings still exist, and they’d be baffled by an ideology that would basically have stopped them from engaging in the entrepreneurship they themselves engaged in.

As with so many redevelopment plans, the Pennytown project(s) has/have been held up for over a decade now. Of course, a proposal to turn the site into affordable housing was met with stiff opposition. One point made in opposition, however, was worth engaging with. Some noted that without public transportation or a very close metro area, the lower-income people who need affordable housing might have trouble finding work or getting around. I know there are answers to this, and I know the same folks pretending to be concerned about this would oppose new transit or densification. If anything, this just points out how a car has become a sort of ticket to fully participating in American life outside of a few really transit-rich places. Yes, I’d like to see that change.

At one point, there was a proposal to turn the property into open space, something New Jersey is famous for. Open space satisfies both NIMBYs and environmentalists. Perhaps in a sparsely populated rural area, open space is good. In denser areas, however, it often merely means patches of green that do little but decorate a deficient land-use pattern, and worse, force development to sprawl further out into the actual, open countryside.

The saga here is too complicated and inside-baseball to bother retelling, but here’s an (archived, now deleted) blog post on one of the proposed redevelopment plans, with lots of comments. Some miss the old businesses. Some think there’s too much retail. Here’s a news story detailing outrage over what admittedly sounds like a fairly large plan for an area that is, sort of, middle-of-nowhere.

And here’s a story from 2018. My understanding is that this kind of long, tortuous process is pretty common in redevelopment—I wrote about a few examples last year—but still, just read this:

Hopewell Township officials bought the property in 2008 with the intent to develop it for affordable housing, but later scrapped the plans. The township will provide opportunities for affordable housing, which will be built on other sites in the township by developers.

The township paid $6.65 million for the Pennytown Shopping Village property, which included 11,200 square feet of office space, two single-family homes, a 5,992-square-foot restaurant, a 44-room motel and 20,657 square feet of retail use.

Hopewell Township subsequently demolished the buildings, with the exception of the historic house on the property.

And here’s the township’s official page for the redevelopment, with dozens of links, and no updates since 2017. You have to wonder how much cash, and how much opportunity cost, is being burned here. For me, one of the strongest arguments for redevelopment and buildings things is that something is usually better than nothing. It isn’t ideological. It’s common sense.

Finally, here’s a forum thread with a ton of photos of Pennytown while it was vacant but still standing. It’s sad. You can tell how nice it was at one time, especially when the area was even more rural and remote. In some ways, things like this put tiny communities on the map.

Beyond being a mildly interesting anecdote or trigger for nostalgia, does the story of Pennytown tell us anything? Maybe.

One thing that occurs to me is that a similar shopping center probably would not be built today. The cost of building has gone up, whether because of NIMBYism or environmental impact statements or more complicated and demanding zoning codes. We don’t really build the way we used to, putting up tiny little buildings on virgin plots. The ease with which ordinary people went into business in those days is astounding. For example, check out my posts about a tiny diner and a 1930s motel, out in the Virginia countryside.

Pennytown was a little hokey but genuinely useful, and it lacked a big box chain or large anchor store. The change in the speed (slower) and scale (larger) of building today probably says something about how regulation can act as a barrier to entry, and how it can go hand in hand with bigness and centralization.

The decline of Pennytown is probably also an example of the bypassing and rerouting effects of the Interstate Highway System. Certainly, the decline of its motel is. Route 31, along with the New Jersey portion of U.S. Route 22, was once on the route to New York City or Philadelphia, depending on your direction and location. In fact, centuries ago, taverns in Pennington hosted Revolutionary-era travelers on the Philly-NYC route.

Most of Pennytown went up in the late 1960s, the tail end of the pre-Interstate wayside building boom. It is hard to imagine a country as large as the United States without some kind of limited-access highway network, and the Interstates are generally understood to have facilitated economic growth. Still, they pulled large amounts of travelers off long stretches of state highways and local roads, aggregating them onto the ugly commercial conglomerations immediately surrounding the Interstate exits, and leaving many small towns and rural communities without traffic and customers. On the other hand, the Interstates changed rural areas in a different and countervailing way: by making travel faster, they slashed commuting times and turned many rural places into exurban bedroom communities. It’s complicated.

But back to Pennytown itself. I’ve always felt that the disappearance of quaint, odd, granular little places and landmarks must do something to our sense of community, and to the richness and variety of our memories. I’m thankful that I got to walk around and feed the ducks at Pennytown when I was a kid. I hope we can build new things that will fill the same niche for people today. I hope little pieces of old places can be preserved, like signs or other artifacts, so that we can have a sense of both continuity and change. Most of all, I hope Pennytown doesn’t remain a vacant lot.

Related Reading:

If you like what you’re seeing, please consider a paid subscription to help support this work. You’ll get a weekend subscribers-only post, plus full access to the archive. And you’ll help ensure more material like this!

Thank you so much for this article. My grandfather, George Briehler, built Stage Depot and Pennytown village and I grew up there with the rest of my family through middle school. He also owned the bowling alley Patricia’s Hiohela, named after his wife and my grandmother, Patricia. It’s amazing to us the positive memories people have of the place, which was so central to our family. I wish my Grandpop was alive to still see how people remembered what he built.

I remember going there when I was a child. There was a peacock, among other birds there, and we used to love if and when it went open up and spread its tail feathers. So beautiful. Other memoirs flooding in like going there and getting an ice cream sundae at the little restaurant after seeing the Ho-Val high school musical with my Dad or cutting off my long blond hair and getting a Dorothy Hamill haircut at the salon which made me so excited. Haha. Fun little memories of a great little place.