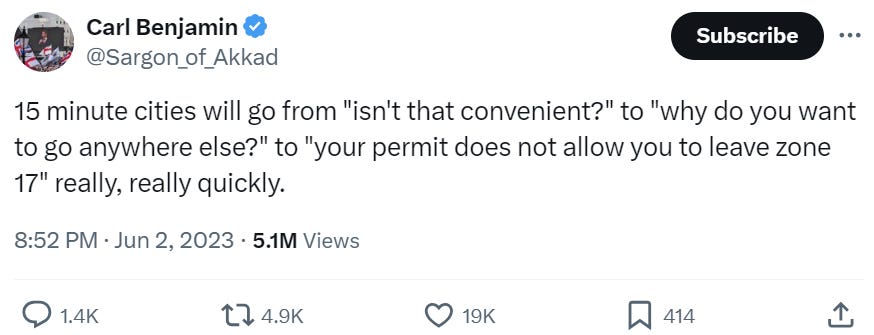

I had a review of urban planner Carlos Moreno’s The 15-Minute City in The Bulwark recently. My take on it surprised me, honestly. I was expecting the book to be about the titular concept, of course, as well as a sort of obvious repudiation of all of the conspiratorial nonsense about the 15-minute city out there. (Everyone from Jordan Peterson to Russell brand is chattering about how 15-minute cities are really basically concentration camps.) Here’s a tweet, for example, that Jordan Peterson affirmingly retweeted:

It’s very, very hard to overstate how utterly insane this is. The idea that making cities more walkable and putting goods and services in better proximity to people—in other words, cities and towns as they always historically existed—is authoritarian or suspect is just…bizarre.

Which is why I was rather unnerved that The 15-Minute City did not, in fact, definitively repudiate everything that is said about it. I found myself a tiny bit less certain that the conspiracy theorists are wrong. And I suppose I understood how people with no background on urbanism stuff at all could end up believing or flirting with this stuff.

There’s another thing I notice, which I focused on in my review. There is a lot of conceptual lack of clarity going on here:

Right from the start, with the brief description on the book’s dust jacket and a series of blurbs from other planners and urban scholars, the exact nature of the 15-minute city is unclear. Is it a succinct slogan for an ancient, traditional idea? A transformative innovation? A return to old wisdom? A fundamental reimagining of our cities?

The 15-minute city is called an “academic concept.” The book flap mentions “returning” to a lost urban way of life. But it also refers to a “new” and “innovative” way to live in cities. One blurb mentions “restoring” proximity to urban neighborhoods, but then praises “innovative ideas.” Another nods to forgotten urban wisdom but then adds that the modern 15-minute city concept is a way to “interpret these basic human needs into concept, and translat[e] that concept into policy.” One refers to an “ecological revolution.” There’s a reference to the “circular economy.” One blurb acknowledges that the 15-minute city is “old-fashioned,” but quickly adds that Moreno has refreshed it with “cutting-edge scientific findings on urban networks and complex adaptive systems.”

There was another line I didn’t fit into here, from the book’s introduction by architect Jan Gehl: “The 15-minute city is a new, yet well-tried concept. In the ‘good old days,’ all the cities, big and small, were 15-minute cities.”

How the hell can something be “new, yet well-tried”? What a lot of highly educated left-ish folks don’t understand is how much of a stumbling block this kind of thing can be for people. It absolutely raises suspicion that if you can’t explain your ideas in clear language, then maybe they’re either bad or nefarious.

Or, as I put it in the review, “Intelligibility induces trust.” I feel at times—maybe I’m putting on my own tinfoil hat here—that some elite types almost purposely try to speak and write in a manner that will make ordinary people suspicious, just to mess with them. The broader point here is that urbanism and good planning require trust. And that trust is broken not just by the YouTube and podcast and Twitter cynics who make money pretending cities are prisons, but the elites who open the door through which those guys drive a truck.

The losers are the regular people.

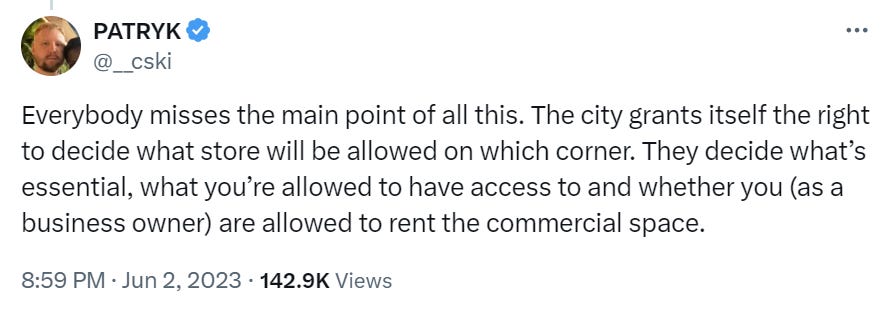

But that conceptual lack of clarity. In some sense, we don’t know what we’re even talking about. There are so many “its” and “theys” and other generalizations. Here’s another right-wing account dunking on 15-minute cities:

Now what he’s describing is…zoning. Which someone points out, to which he actually replies, “I agree zoning laws should be abolished. But that’s not the idea behind 15min cities, unlike some try to portray it as.” (After replying to someone else “govern me harder daddy.”

Who’s to say what the idea behind 15-minute cities is? Carlos Moreno is kind of entitled to that, I guess. But the book isn’t a doctrinal formulary. Nor is the concept trademarked. The name, like all sorts of trendy names—including New Urbanism—gets appropriated by everybody for whatever thing they want it to mean. We’re just not really talking about the same things.

I remember when I was writing about a scheme in Oxford, England to restrict car traffic through certain neighborhoods, I found that a bunch of lefty urbanists had actually not heard of it or didn’t know it did that: in other words, they were unaware of the grain of truth in some of the stuff the other guys were saying.

I remember a conversation I had with my dad, years ago, after I watched Food, Inc. or something in college. I was explaining the difference between “food sovereignty” and “food security”/“food insecurity.” He laughed, “What, is the food insecure?” He wasn’t making fun of the idea so much as finding the term sort of self-evidently ridiculous. I’ve seen this a lot: the phenomenon where bland, boring bureaucrats end up sounding crazy and radical to regular people.

All of this is to say not that elites are to blame for conspiracy theories. Rather, regardless of what those guys are saying or not saying, I think we all have a sort of duty to use sober, intelligible, plain language when we discuss policy, especially ideas that are unfamiliar. I think of that as a kind of professional responsibility and code of conduct that I hold myself to. So many of our flashpoints come down to words and terms, things that scandalize regular people or make them wonder, what kind of person talks like that?…

Let me tell you something else, not to toot my own horn but to observe a dynamic: a bunch of urbanists and planners liked my various social media posts for this book review. Some left positive comments. A lot of people basically seemed to think I was right that Moreno was a bit too “gee whiz, look at my great idea!” in this book, and not interested enough in clearly communicating it to a broad audience.

Now that isn’t something most of them would probably say on their own, because Moreno is a big name right now in urban planning, and the 15-minute city is a trendy concept. I’m able to intuit and say things that people with more at stake in these professions are not. And I think that’s one of the values of the work I do. I’m not saying they’re cowards or go-along-to-get-alongers or whatever. They have their role. And I see myself as having mine. (Sign up or subscribe if you want to support what I do here!)

I talk later on in the review about how when the signal in the book actually is something like “Make cities more livable and dense with stuff people want”; the jargon and weird language and occasional odd example really is the noise. This book is not some secret blueprint and the vast majority of urbanists are not dupes or secret foot soldiers in the plot. There’s a lot of diversity in our broad movement and nobody owns or fully claims any of it.

Some stuff that can sound a little hokey is really just…good stuff: Moreno mentions a pilot program to open public schools on Saturdays and make their grounds public shared spaces—basically, very low-cost impromptu parks. He uses the phrase “zoned lives,” which I find a really insightful way to point out how zoning fragments our own lives as much as it does the built environment. There’s a lot of refreshingly practical stuff alongside a whole lot of jargon and wordiness. The book, unfortunately, is a slog.

It also raises a question that conservatives have asked me before: How do you answer the question of why the most urbanist places are also the most secular and socially progressive? In other words, does whatever “urbanism” is necessarily come packaged with all that other stuff? My answer—which Moreno does in fact suggest, in looking at Rust Belt America and small European villages—is that small towns exist. They are urban in form but frequently with a much more conservative culture.

Nonetheless, at times, I get the sense that there’s something like a tragedy in the old Greek sense happening here: the elites can’t help but inflate a very simple idea with words words words, and in turn they disguise—conceal—the underlying idea and turn regular people against them. The desire to elevate yourself can make you sound ridiculous. And the intuition to embrace normalcy and straightforwardness can make you go crazy. To the extent that there is anything nefarious about the 15-minute city, it is in appearance and words; at worst—though bad and odd enough—it is a sheep in wolf’s clothing.

Related Reading:

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,100 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

In my observations of progressive policy wonks (as we call them in Australian slang) is the absolute worst thing you can accuse them of is being ‘conservative’. They are so blind to the notion that the past is a) a useful record of things that succeeded and failed, b) people in the past are NOT morons and c) progress is only progress if it’s ‘revolutionary’ so they have to reinvent the wheel all the time to sell it… but they only talk to other progressives, otherwise they’d realise that their idea is not that revolutionary.

Example: Multigenerational households are the ‘revolutionary’ way to solve the aged care crisis! But only to people who thought it was a good idea to section off and warehouse the elderly and infirm to be cared for by ‘experts’, ie poorly paid carers on 12 hr shifts and a few doctors who couldn’t get a better offer. Meanwhile every Asian/Eastern European/Islander/ is laughing at them because they never thought it was a good idea to warehouse their elders away from families in the first place! They never used to be called ‘multigenerational households’ they used to be called families or just households.

That is just one example of how ‘progressives’ can’t admit to themselves that their ‘progressive revolution’ has actually destroyed something good and human and the attempt at engineering has failed miserably so they have to ‘progress’ with new words for a normal human activity and end up looking like idiots to normal people and conservatively dispositioned people (like me). It’s the chief reason I soured on public policy in my undergrad days and went deeper into philosophy and theory. Exasperation is one word to describe this idiotic merry go round and lack of humility to admit that sometimes the truly progressive thing to do when you’ve taken a wrong turn is to go back till you find the right road.

In most cities strip malls were located in walking distance of most neighborhoods, and served as complete local downtowns. We only needed to go all the way downtown for specialized things like banking.

Indoor malls and big boxes sucked the life out of strip malls, which now hold mostly dubious and quasi-legal stores. Maybe the movement would be easier to understand if it talked about strip malls instead of minutes.